by Tim Sommers

Imagine a slave in ancient Rome with a very generous master. A master so, generous, in fact, that this slave lives their entire life doing as they choose and their master never once interferes with them. The liberal view of liberty, enshrined, for example, in the U.S. Constitution, is that liberty, or at least the most fundamental kind of political liberty, is the right to not be interfered with, especially by the government. This freedom not to be prohibited from or impeded in doing what one will is often called “negative liberty” – as opposed to “positive” liberty which implies the will (autonomy/self-directedness) and the means (money, for example) – and not just the absence of interference.

The point of the generous master hypothetical is that the slave seems to be free, in the negative, liberal sense; that is, free from interference, specifically, from their master. Yet surely, as a slave, even as the slave of a very, very generous master, one is not free. There must be something wrong, then, with the liberal idea that freedom is simply freedom from certain kinds of outside interference.

Political philosopher Phillip Pettit, who formulated this hypothetical, says, and it is hard to argue with him, that the slave is not free since the master could have interfered at any point – even though they didn’t. This kind of unfreedom he calls “domination” and, so, his account of freedom he calls “liberty as non-domination” or the “republican” theory.

Over the last twenty years, Pettit has been attempting to resuscitate, he says, “the republican viewpoint as a political philosophy.” He’s been developing a “neorepublicanism” which he thinks is founded on a significant theoretical difference between the republican and liberal views of political freedom.

Pettit thinks that his hypothetical generous master shows that the master and slave have a hierarchical relation, even if the dominant party never exercises their power. Arguably, the master still oppresses the slave without ever interfering with them. Read more »

In 1977, I was a student at the University of Pennsylvania, majoring in French Literature. I was 19 years old and pregnant with my first child. I would dress in a long shapeless plaid green and black dress, tie my hair with an off-white headscarf, and wear Dr. Scholl’s slide sandals trying very hard to blend in and look cool and hippyish, but that look wasn’t really working well for me. The scarf at times became a long neck shawl and the ‘cool and I don’t care’ 70’s look became more of a loose colorless dress on top of my plaid dress, giving me the appearance of a field-working peasant. My sandals added absolutely nothing, except making me trip on the sidewalks.

In 1977, I was a student at the University of Pennsylvania, majoring in French Literature. I was 19 years old and pregnant with my first child. I would dress in a long shapeless plaid green and black dress, tie my hair with an off-white headscarf, and wear Dr. Scholl’s slide sandals trying very hard to blend in and look cool and hippyish, but that look wasn’t really working well for me. The scarf at times became a long neck shawl and the ‘cool and I don’t care’ 70’s look became more of a loose colorless dress on top of my plaid dress, giving me the appearance of a field-working peasant. My sandals added absolutely nothing, except making me trip on the sidewalks. The writer Tabish Khair was born in 1966 and educated in Bihar before moving first to Delhi and then Denmark. He is the author of various acclaimed books, including novels

The writer Tabish Khair was born in 1966 and educated in Bihar before moving first to Delhi and then Denmark. He is the author of various acclaimed books, including novels

Sughra Raza. Rain. Hund Riverbank, Pakistan, November 2023.

Sughra Raza. Rain. Hund Riverbank, Pakistan, November 2023.

In the 21st century, only two risks matter – climate change and advanced AI. It is easy to lose sight of the bigger picture and get lost in the maelstrom of “news” hitting our screens. There is a plethora of low-level events constantly vying for our attention. As a risk consultant and

In the 21st century, only two risks matter – climate change and advanced AI. It is easy to lose sight of the bigger picture and get lost in the maelstrom of “news” hitting our screens. There is a plethora of low-level events constantly vying for our attention. As a risk consultant and  The first time I became aware of Friedrich, many years ago, I was in Zurich to meet an elderly Jungian psychoanalyst—my head stuffed with theoretical questions and eerie dreams with soundtracks by Scriabin. Walking down the Bahnhofstrasse, I passed a bookstore window displaying a stunning art book with the elegant title Traum und Wahrheit (Dream and Truth) and a simple subtitle: Deutsche Romantik. I didn’t yet speak German, but I knew enough to be interested. The book was too heavy for my luggage. I bought it anyway and had it shipped.

The first time I became aware of Friedrich, many years ago, I was in Zurich to meet an elderly Jungian psychoanalyst—my head stuffed with theoretical questions and eerie dreams with soundtracks by Scriabin. Walking down the Bahnhofstrasse, I passed a bookstore window displaying a stunning art book with the elegant title Traum und Wahrheit (Dream and Truth) and a simple subtitle: Deutsche Romantik. I didn’t yet speak German, but I knew enough to be interested. The book was too heavy for my luggage. I bought it anyway and had it shipped. What lured my eye to the cover as I passed by was a partial view from one of my now favorite Friedrich paintings, Das Große Gehege (The Great Enclosure)—a cool marshy landscape evoking real ones I would later see from train windows. How could just a corner of a painting have such power? It was the light, the late afternoon saturation of yellow, the black shadowed trees, and the hint of evening gloom already visible as gray on the horizon even though the sky above was still blue. I was captivated.

What lured my eye to the cover as I passed by was a partial view from one of my now favorite Friedrich paintings, Das Große Gehege (The Great Enclosure)—a cool marshy landscape evoking real ones I would later see from train windows. How could just a corner of a painting have such power? It was the light, the late afternoon saturation of yellow, the black shadowed trees, and the hint of evening gloom already visible as gray on the horizon even though the sky above was still blue. I was captivated.

Because I have taken some medical leave from 3QD in the past few weeks, we have not had magazine posts for a while, though we have continued to post curated articles in the “

Because I have taken some medical leave from 3QD in the past few weeks, we have not had magazine posts for a while, though we have continued to post curated articles in the “

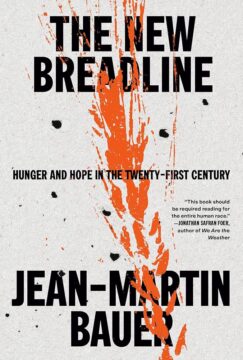

Many decades ago, I was fortunate to have had the opportunity of living in India for several years. I was enthralled by that country: its cultural richness; the environment; the food, but most of all the friendliness and warm hospitality of its diverse people. There were, of course, issues that confounded me and stark contradictions stared back at me from many directions, but of particular concern was the scale of the poverty amongst vast sections of the population, an issue that visited me at home frequently. A small begging community gathered regularly at my front gate, hungry and calling out for food. As my knowledge of the Indian social structure deepened, I came to understand that these people belonged to the most oppressed castes in Indian society and not only they, but a multitude of others were living in poverty, and with hunger.

Many decades ago, I was fortunate to have had the opportunity of living in India for several years. I was enthralled by that country: its cultural richness; the environment; the food, but most of all the friendliness and warm hospitality of its diverse people. There were, of course, issues that confounded me and stark contradictions stared back at me from many directions, but of particular concern was the scale of the poverty amongst vast sections of the population, an issue that visited me at home frequently. A small begging community gathered regularly at my front gate, hungry and calling out for food. As my knowledge of the Indian social structure deepened, I came to understand that these people belonged to the most oppressed castes in Indian society and not only they, but a multitude of others were living in poverty, and with hunger.