by Claire Chambers

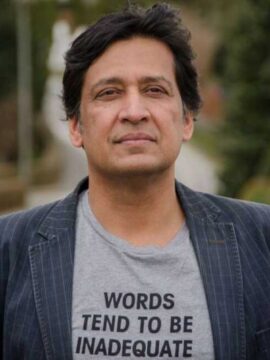

The writer Tabish Khair was born in 1966 and educated in Bihar before moving first to Delhi and then Denmark. He is the author of various acclaimed books, including novels The Thing About Thugs, How to Fight Islamist Terror from the Missionary Position, and Just Another Jihadi Jane. He has also published poetry collections such as Where Parallel Lines Meet and Man of Glass. Khair’s academic writing includes studies of alienation in contemporary Indian English novels, the postcolonial gothic, and the new xenophobia.

The writer Tabish Khair was born in 1966 and educated in Bihar before moving first to Delhi and then Denmark. He is the author of various acclaimed books, including novels The Thing About Thugs, How to Fight Islamist Terror from the Missionary Position, and Just Another Jihadi Jane. He has also published poetry collections such as Where Parallel Lines Meet and Man of Glass. Khair’s academic writing includes studies of alienation in contemporary Indian English novels, the postcolonial gothic, and the new xenophobia.

In addition is Quarantined Sonnets, a sequence about Covid-19 published soon after the virus went global. In this slim volume, Khair rewrites Shakespearean sonnets with humour as well as pathos in order to examine ageing, sexuality, and other subjects. Twenty-one Shakespearean sonnets are reinterpreted to reflect the changing face of love and mortality amid health disaster. Above all, the poetry collection examines how economies are impacted by the virus, and satirizes rampant capitalism against the backdrop of the Covid-19 pandemic. Khair does something similar in his most recent novel The Body by the Shore, for which I wrote a ‘Reader’s Guide’ and so I will not say too much about it here. In both his poetic and fictional works he sends shots across the bow against materialism, corporate greed, and social inequality.

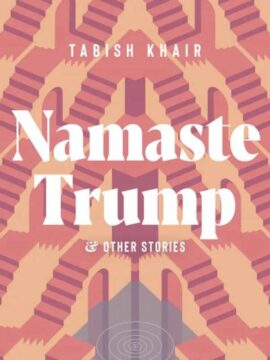

Similarly, at least two stories from Khair’s 2023 collection Namaste Trump, ‘Shadow of a Story’ and, especially, ‘Namaste Trump’, have coronavirus as a fulcrum. The narrator of ‘Shadow of a Story’ is angered by India’s plight amid the 2021 catastrophe of ‘pyres burning, bodies floating down the Ganges during the pandemic’ (167).

The titular tale ‘Namaste Trump’ is set earlier on, around the time of the American president’s state visit to India in February 2020, and examines the onset of Covid. The story centres on a young servant with physical and mental disabilities, employed under near-feudal conditions by a wealthy Hindu Right family. As Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s migrant labour crisis escalates, the family sends the boy back to his village in Bihar. Disconnected from his supposed home and attached to the metropole, Chottu flees to live among marginalized city-dwellers. Eking out an existence in a nearby dump, he contracts the virus there and goes on to die from it.

Khair’s portrayal of the deep divisions between rich and poor exposed by Trump’s visit resonates with this chilling analogy made by the novelist and activist Arundhati Roy in 2021:

Khair’s portrayal of the deep divisions between rich and poor exposed by Trump’s visit resonates with this chilling analogy made by the novelist and activist Arundhati Roy in 2021:

The precise numbers that make up India’s Covid graph are like the wall that was built in Ahmedabad to hide the slums Donald Trump would drive past on his way to the ‘Namaste Trump’ event that Modi hosted for him in February 2020. Grim as those numbers are, they give you a picture of the India-that-matters, but certainly not the India that is. In the India that is, people are expected to vote as Hindus, but die as disposables.

Khair’s ‘Namaste Trump’ takes a gothic turn in examining the India that is. Accordingly, the disposable Chottu returns as a vengeful ghost, haunting his exploitative employers and reminding them of the ethical consequences of their neglect.

Khair now lives in a village off the town of Aarhus, a locale that looms large in both How to Fight Islamist Terror and The Body by the Shore. He describes himself as part of a long, complex and obscured history of ‘small town cosmopolitanism’. Two specific minor cities feature in this thinking: not only Aarhus on the eastern coast of Denmark, home of the Jyllands Posten newspaper and its cartoons affair of 2005, but also Gaya in India’s eastern province of Bihar. He has encountered parochialism and prejudice in these small, sometimes small-minded places, which provide material for his fiction. Khair nonetheless avows that cosmopolitanism does not have to entail living in the world’s biggest and most multicultural cities. This is because, the author believes, reading takes you to other realms, creating ‘brave (new and old) words’.

In a chapter, ‘The Making of a Muslim’ he wrote for an essay collection edited by Caroline Herbert and me nearly a decade ago, Khair describes being a young writer who had just left Gaya and was trying to make a living as a journalist in Delhi. He sparked healthy debate with his fellow Muslims at that flashpoint moment in the late 1980s by subjecting Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses to nuanced evaluation. However, he soon faced greater backlash from the Hindu Right for criticizing the Mahabharata TV serial. After writing a further article about Islam in India, Khair incurred local hostility in Gaya, but his father, a religious Muslim, intervened and defused the situation. Later, after moving to Denmark, a reporter there distorted his story so as to sensationalize Muslim blowback against Khair’s qualified praise for Rushdie. Instead of highlighting the entanglement of local conservatism with global issues, the Danish journalist’s report bore the misleading headline: ‘Budding Indian writer pays dearly for supporting Rushdie’. These were some of the novelist’s early encounters with what he calls ‘fundamentalist’ approaches to literature.

Rushdie pops up again, along with Amitav Ghosh (about whose writing Khair and I have written in the same volume) in the pandemic-inflected tale ‘Shadow of a Story’. Its frame narrative features a speaker who seems semi-autobiographical of Khair, given that he recalls his early zeal for Rushdiean seas of stories while researching a PhD in Gaya. Once Covid-19 comes to Indian shores, however, this narrator has to grapple with friends’ faith in ‘consuming and bathing in cow dung […] as a cure or a protection’. Confronted with misinformation, he loses his faith in narrative, thinking: ‘Stories are also terrible things, like God, who, after all, is the greatest story of all!’ The narrator’s equation of religion with fake news implies an atheism which will be modified in Khair’s own theorizations into agnostic criticism.

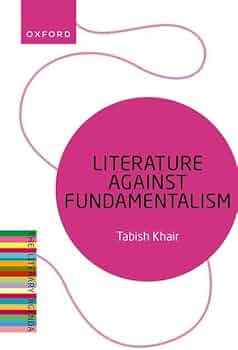

His new nonfiction work is really a short literary manifesto. Literature Against Fundamentalism argues that literature counters both religious and political extremism by promoting complex reading and critical thinking. ‘Fundamentalists’ of all stripes, including new atheists like Christopher Hitchens and Richard Dawkins, simplify texts, missing subtleties and smoothing out uncertainties. Such fundamentalism, whether Muslim, Christian, Marxist/Leninist, corporatist, or atheist, ‘insists on authoritative readings, authoritative iterations of the text, totally ahistorical or narrowly historical contextualization of the text, controls over translations, a narrow priesthood-scholarship of accredited commentaries’. Learning to read closely fosters understanding and combats such reductive mindsets prevalent in society. The ‘antidote’ to fundamentalist interpretations, according to Khair, lies not in conveying alternative messages but teaching literary skills.

His new nonfiction work is really a short literary manifesto. Literature Against Fundamentalism argues that literature counters both religious and political extremism by promoting complex reading and critical thinking. ‘Fundamentalists’ of all stripes, including new atheists like Christopher Hitchens and Richard Dawkins, simplify texts, missing subtleties and smoothing out uncertainties. Such fundamentalism, whether Muslim, Christian, Marxist/Leninist, corporatist, or atheist, ‘insists on authoritative readings, authoritative iterations of the text, totally ahistorical or narrowly historical contextualization of the text, controls over translations, a narrow priesthood-scholarship of accredited commentaries’. Learning to read closely fosters understanding and combats such reductive mindsets prevalent in society. The ‘antidote’ to fundamentalist interpretations, according to Khair, lies not in conveying alternative messages but teaching literary skills.

Khair further contends that literature demands an ‘agnostic’ approach to reading. Building on Edward W. Said’s idea of secular criticism, Khair’s modification is one that encompasses doubt, engages with both language and reality, and recognizes the fluidity and contingency of both. As he writes:

The position adopted is, once again, that of an agnostic: it rests on the assumption that one has to both trust and distrust, believe and not believe, empathize and judge, and one has to come to a contextualized conclusion through such a process of reading.

His language here is reminiscent of Rushdie’s offhand instructions ‘Believe, don’t believe’ from Midnight’s Children. Such a dual lens of credulity combined with scepticism, essential to truly understanding literature, extends beyond the text itself and becomes a crucial mode for interpreting the world.

Rather than countering extremism with equal but opposite arguments, Khair posits that agnostic engagement with texts is vital for human existence. Such an approach necessitates an active ‘excavation’ on the part of the reader. Excavating and co-creating empowers readers to decipher coded language and tackle gaps and silences within both oral and textual stories.

It is in relation to gaps and silences that Khair’s analysis chimes with Jacques Rancière’s theorization of the paradox of ‘mute speech’. The French scholar defines this as a resonant silence that through ‘the music of its muteness’ eloquently attests to wisdom mere words cannot convey. Rather than ‘corralling’ the text’s muteness, its ‘gaps’ and ‘incongruences’, Khair holds that agnostic reading readily embraces them.

It is in relation to gaps and silences that Khair’s analysis chimes with Jacques Rancière’s theorization of the paradox of ‘mute speech’. The French scholar defines this as a resonant silence that through ‘the music of its muteness’ eloquently attests to wisdom mere words cannot convey. Rather than ‘corralling’ the text’s muteness, its ‘gaps’ and ‘incongruences’, Khair holds that agnostic reading readily embraces them.

Yet this way of reading does not accept false claims, instead encouraging readers to probe ‘alternative facts’ in a post-truth, digitalized world. By pushing the limits of language and metaphor, literature teaches us to at once trust and question ideas – relying on ‘neither-both’ thinking, in Khair’s vivid terminology.

This leads to the word ‘contextualiz[ation]’ which rounds off the block quote and which is pivotal to Khair ’s vision. He takes pains to stress, however, that contextualized criticism does not entail a relativist framing of the world. Championed by some postmodernists and poststructuralists, such a philosophical stance also veers into extremism. Its proponents sometimes go as far as intimating there is no reality outside of subjective thought, language, and the text. Relativism often rests on my truth, whereby the individual observer ‘becomes the truth, as if their observation is beyond any context’. By contrast, contextualization entails an awareness of the differences in perception caused by viewers’ various standpoints. Agnostic reading fosters open-minded contextual thinking without getting stuck in the intellectual cult-de-sac of extreme relativism.

Literature Against Fundamentalism is deeply concerned with science as an important adjacent paradigm to the arts. In one of the most interesting sections of the volume, which departs from its usual canonical preoccupation with Anton Chekhov, William Shakespeare, Emily Bronte, and Mark Twain, Khair examines writing by the plant scientist Merlin Sheldrake and ecological storyteller Robert Macfarlane. These authors’ work on fungi and mycorrhizal networks illuminates cooperative, non-hierarchical relationships that exist in nature. The Danish-Indian novelist acknowledges Macfarlane’s influence on his own writing, praising Underworld: A Deep Time Journey as ‘admirable’ for the way it ‘press[es] language to the utmost’. Khair also mentions Sheldrake, describing a walk the biologist went on with the nature writer in Epping Forest, about which Macfarlane writes in Underworld.

Literature Against Fundamentalism is deeply concerned with science as an important adjacent paradigm to the arts. In one of the most interesting sections of the volume, which departs from its usual canonical preoccupation with Anton Chekhov, William Shakespeare, Emily Bronte, and Mark Twain, Khair examines writing by the plant scientist Merlin Sheldrake and ecological storyteller Robert Macfarlane. These authors’ work on fungi and mycorrhizal networks illuminates cooperative, non-hierarchical relationships that exist in nature. The Danish-Indian novelist acknowledges Macfarlane’s influence on his own writing, praising Underworld: A Deep Time Journey as ‘admirable’ for the way it ‘press[es] language to the utmost’. Khair also mentions Sheldrake, describing a walk the biologist went on with the nature writer in Epping Forest, about which Macfarlane writes in Underworld.

Sheldrake and Macfarlane affirm that it is the job of authors to bend language into non-anthropocentric representations of the nonhuman, and Khair understands the assignment. In The Body by the Shore he takes it as his task to depict those ‘networks of sustenance’ that exist between trees and are facilitated by fungi. Khair’s references to roots and shoots in this novel enable plant-based perspectives on hidden subterranean networks, while hinting at the possibility of transformed models to address Covid’s metamorphoses.

Khair’s newest works The Body by the Shore, Namaste Trump, and Literature Against Fundamentalism reinforce his longstanding commitment to defying the simplistic narratives that undergird both extremism and corporatism. By advocating for an agnostic approach to reading, Khair encourages us to engage critically with texts as well as the reality that is out there but impossible for a single individual to grasp. In doing this, a flexible contextual specificity that thwarts rigid interpretations is vital.

In each of his published texts, Khair addresses the limitations of language, striving to push its boundaries and amplify silences that speak volumes. His writing urges readers to question, and ultimately to peer beyond surfaces into what Sheldrake is quoted as calling ‘the understorey’s understory’. This makes literature a sharp tool against the forces of extremism, cutting through the polarizing fog of our post-pandemic world.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.