by Mary Hrovat

Mission to Earth: Landsat Views the World, Nicholas M. Short, Paul D. Lowman, Jr., Stanley C. Freden, William A. Finch, Jr. (published 1976)

I found this book in a library at Indiana University when I was a student in the mid-1980s. I spent hours fascinated by the beauty of the photographs and the quiet, precise poetry of the geographical and geological terminology in the accompanying text.

Satellite images were not as readily available back then, and this book provides a rich banquet of them. Maps in the front of the book show where to find images of each part of the planet. First I looked up places I knew or had visited, and then I looked up places I wanted to visit or was curious about, and finally I just browsed. I’d always been interested in maps, with their place names and the history behind them. This book expanded that experience by giving me the geological, ecological, and human context of each image. It was endlessly interesting.

The book also expanded my horizons in another way. I had no theological qualms about the age of Earth or the universe, but I’d been shown a narrow world, growing up—a world centered on sin and redemption, where Earth is ultimately a way station between two eternities. I’d been a homebody as a child, caught up in my parents’ religious scruples and anxiously examining my behavior for not only sinful tendencies but also insufficient devotion to the divine.

This book was one of the things that released me to a wider view of life; it nurtured an enchantment with Earth, its dynamic intricacy and complex history, its reality as a thing in itself rather than a divine stage set. It absorbed me in the features and processes of the living planet. I didn’t realize it at the time, but I can see now that it sowed the seeds of a view of Earth itself as sublime and holy, in a completely natural sense.

I loved the patterns that appear when you look at Earth from a satellite: sand dunes, watersheds, the features left behind by glaciers. I was excited to learn how legible the landscape is when you look at it in terms of geological processes and how Earth can be seen as a set of interlocking systems. The crops and plant species that grow in a particular location, and the reasons they grow there, are linked to Earth’s history at each particular place. The beautiful descriptions of each image drew me gently out of myself, in the best possible way.

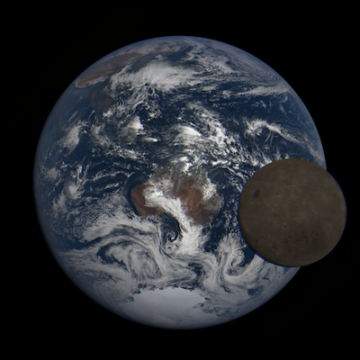

At the same time, I was becoming fascinated by space exploration. I sought out images of Jupiter and Saturn and their moons from the Voyager missions. I also read about the Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo programs, and about the possibilities for humans to live on other planets or moons or in space colonies. The images in the Landsat book left me craving a view of Earth from space. It seems somewhat paradoxical to me now, but at the time I thought it might be possible and even desirable to leave my home planet behind, at least for a while.

∞

The Firmament of Time, Loren Eiseley (published 1960)

I found this book in a very small library on a 9200-foot peak in a tiny community called Sunspot, in southern New Mexico, in the summer of 1987. I was at the Sacramento Peak Observatory, part of the National Solar Observatory, as a research assistant. I’d just returned from a brief visit to Phoenix for my maternal grandmother’s funeral.

Granny had lived with us throughout my childhood, and she was the first person close to me to die. I’d left my parents’ religion several years earlier and didn’t believe in heaven and hell, but I didn’t have much of a sense of the meaning of death in the absence of the concept of eternal life. While I was in Phoenix, I responded to Mom’s religious statements supportively; I didn’t share her beliefs, but I knew they comforted her. As I drove back to New Mexico, I began to consider how I might be consoled and reconciled to Granny’s death.

One night shortly after I returned to the observatory, I felt restless and unsettled. As I often do when at a loose end, I sought the company of books, in this case those in the observatory’s library, a very informal setup in the house across the street from where I was living. The books appeared to be a random and interesting assortment rather than a curated collection. The wonderful title of this book caught my attention, and I pulled the book from the shelf, leafed through it, and carried it off to read.

The Firmament of Time is a set of six lectures on how a natural, or secular, view of life emerged. When I first read it, I was most interested in how we could understand human life in terms of nature rather than as part of a religious story, and how humans are related to nature. (The second essay is called “How Death Became Natural.”) I feel fortunate to have found the book at that moment, and it gave me much to think about.

What stays with me most indelibly is a passage I happened across while I stood alone in the library leafing through the book. It put my family’s grief into a much larger context. In the fourth lecture, Eiseley quotes from a talk he had given earlier, about a Neanderthal burial site discovered in a French cave near La-Chapelle-Aux-Saints in 1908: “Here, across millennia of time, we can observe a very moving spectacle. For these men … had laid down their dead in grief. Massive flint-hardened hands had shaped a sepulcher and placed flat stones to guard the dead man’s head. A haunch of meat had been left to aid the dead man’s journey. Worked flints, a little treasure of the human dawn, had been poured lovingly into the grave.”

Eiseley goes on to describe these as human actions, essentially the same as those we perform today when we grieve a loss. When I first read them, I remembered how we had dropped roses gently onto my grandmother’s casket after it was lowered into the ground, a symbolic, fruitless, essential gesture. It’s hard to articulate why, but Eiseley’s words comforted me then and comfort me now.

∞

The History of Earth: An Illustrated Chronicle of an Evolving Planet, William K. Hartmann and Ron Miller (published 1991)

I was given this book as a Christmas present in the early 1990s. I had graduated by then and was working at the university library in Bloomington, not in astronomy. My mental model of the universe had expanded sufficiently to encompass a more complete view of Earth’s history, and still my mind was stretched and boggled as I came to grasp it in the pages of this book. I knew the names and the rough order of various geological periods, but mostly I’d learned about the more recent ones. I hadn’t understood how recently (in geological terms) life had emerged on Earth. This book might have given me my first inkling that the term habitable should be qualified when applied to planets: habitable for certain types of organisms, at certain times in its history, over some of its surface.

I spent hours with this book, absorbing stories I hadn’t known and thrilling at the illustrations, which consist of artist’s conceptions of events in Earth’s history. The chapters about the earliest stages of Earth’s history were the most interesting to me on my first reading. I was floored by a painting of Earth halfway through its history: eroded volcanic features without a hint of vegetation.

I also learned about more recent events. For example, I learned that five to six million years ago, during the Miocene, much of the Mediterranean basin dried out, leaving vast salt beds at the bottom of the basin. A land bridge connected Europe and Africa where the Strait of Gibraltar is now located. A painting in the book envisions one of the waterfalls that were thought to periodically refill the basin with dramatic rapidity between 6.5 and 5 million years ago. (This episode is called the Messinian salinity crisis. It still fascinates me.)

Because this book is over 30 years old, I’m sure that some of the scientific research it describes has been superseded by more recent work. I still browse through it sometimes, though. It reminds me that the familiar Earth I see every day has been many other Earths. The Landsat book introduced me to the idea that the geological landscape is a palimpsest. This book revealed the depth of layers in that palimpsest and showed that much of Earth’s history happened so long ago that every trace of it has vanished.

∞

Rare Earth: Why Complex Life Is Uncommon in the Universe, Peter D. Ward and Donald Brownlee (published 2000)

I read this book shortly after it was published because I was curious about the various factors that affect Earth’s habitability. Reading this book enhanced my appreciation for Earth, its systems and processes, its beauty and its vulnerability.

Ward and Brownlee describe in detail 18 factors that affect Earth’s habitability. These factors include the characteristics of Earth’s larger context—the size of the Milky Way and the solar system’s location in the galaxy, as well as the size of the sun and Earth’s distance from it. They also include characteristics of the solar system and Earth itself, such as the presence of other planets and the composition of Earth’s atmosphere. You perhaps will have gathered how much I enjoy seeing the big picture, and a book that traces Earth’s history back to the origin of the chemical elements is wondrous reading indeed. I hadn’t known that plate tectonics, tides, and even the presence of Jupiter contribute to making Earth habitable.

The authors assumed that animal life on other planets would be broadly similar to that on Earth; I wonder whether there are other kinds of complex life that we can’t easily imagine and that don’t require the conditions that complex life on Earth does. However, stability is a key factor in Earth’s habitability, and the development of complexity likely requires stable conditions.

Again, this book is more than 20 years old, and some of the science has undoubtedly changed. But at least one factor, the presence of plate tectonics, seems to be gaining recognition as a feature, possibly an uncommon one, that influences the habitability of a planet. In any event, this book gave me a greater appreciation of the sweet spot we occupy in space and time, and also of the brevity, in geological terms, of habitable periods on Earth. It brought home to me the complexity of the environmental systems we tinker with so heedlessly.

For various reasons, I’d become much less enamored of human space travel by the time I read this book. The book itself strengthened my growing sense that I wouldn’t want to live in space even if I could. I no longer think humans should colonize the solar system or establish space colonies, and I doubt that they’d succeed if they tried. Instead, rather than bring our bad human habits to untouched worlds, I think we should care for and appreciate the planet we’ve been given, and learn to live within its limits. (Sorry, younger space-obsessed self.)

∞

I didn’t seek these books out as guides for the long, convoluted process of leaving the religion in which I was raised. I didn’t even recognize at the time that they were part of that process. I was drawn to them by the exhilaration of learning about complex systems and deep history and expanding my mental model of the universe. It’s such a heady thing when a short-lived human mind comprehends, however partially and incompletely, the larger processes of which its life is a part.

But I’ve received even more than that. Only now can I trace the ways that these books, and others like them, have drawn me toward an appreciation of immanence over transcendence, a sense of the richness and depth of the present moment, a love of the details of quotidian events and the everyday things that surround me. And the journey continues.

∞

You can read more of my work at MaryHrovat.com.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.