by Daniel Shotkin

I was in 9th grade when I first heard the name Rudyard Kipling mentioned in school. My history teacher had decided to inaugurate a unit on imperialism, and Kipling’s zealous verses soon rang loudly through the classroom:

Take up the White Man’s burden—

Send forth the best ye breed—

Go bind your sons to exile

To serve your captives’ need;

To wait in heavy harness

On fluttered folk and wild—

Your new-caught, sullen peoples,

Half devil and half child.

My teacher explained that Kipling exemplified the racist and jingoistic attitudes of late-19th-century European colonial powers. I was surprised because, to me, Kipling represented something else entirely.

I didn’t disagree with my teacher’s assessment—certainly, no one could after hearing a poem called “The White Man’s Burden.” But my confusion wasn’t unwarranted; it stemmed largely from the fact that the Kipling recited by my teacher and the Kipling I had known prior to that fateful history class seemed to be two radically different authors. Read more »

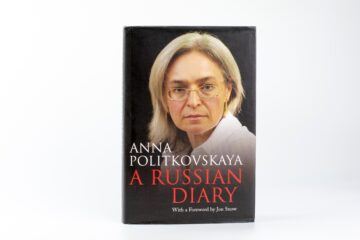

It’s raining in Russia. Thunderheads boil up in the afternoon heat over there, behind the limestone block fortress on the other side of the river. Which is not a wide river. You can shout across it.

It’s raining in Russia. Thunderheads boil up in the afternoon heat over there, behind the limestone block fortress on the other side of the river. Which is not a wide river. You can shout across it. Sughra Raza. On the Train to Franzensfeste. September, 2024.

Sughra Raza. On the Train to Franzensfeste. September, 2024. Even if you are sympathetic to Marx — even if, at any rate, you see him not as an ogre but as an original thinker worth taking seriously — you might be forgiven for feeling that the sign at the East entrance to Highgate Cemetery reflects an excessively narrow view of the political options facing us.

Even if you are sympathetic to Marx — even if, at any rate, you see him not as an ogre but as an original thinker worth taking seriously — you might be forgiven for feeling that the sign at the East entrance to Highgate Cemetery reflects an excessively narrow view of the political options facing us.