by Richard Farr

Even if you are sympathetic to Marx — even if, at any rate, you see him not as an ogre but as an original thinker worth taking seriously — you might be forgiven for feeling that the sign at the East entrance to Highgate Cemetery reflects an excessively narrow view of the political options facing us.

Even if you are sympathetic to Marx — even if, at any rate, you see him not as an ogre but as an original thinker worth taking seriously — you might be forgiven for feeling that the sign at the East entrance to Highgate Cemetery reflects an excessively narrow view of the political options facing us.

For years I had planned to come here, to his final resting place, and pay my genuine if heavily qualified respects. In the end the visit was almost accidental. My wife and I were walking off vast quantities of melted cheese sandwich that had accosted us in Camden Market, our destination was Hampstead Heath, and Google Maps suggested to us that the detour was slight.

The six quid you pay to get in helps the Cemetery Trust keep most of this beautiful sanctuary neat and trim, with broad main avenues and benches spaced at convenient intervals for rest and contemplation. But much of its appeal lies in a strange duality of character. Large sections are so crowded, so ivied, so root-heaved and broken that I was put in mind of Mayan temples in the Yucatan, reduced to fragments and being digested by the rainforest. Stones pristine and sundered. Inscriptions legible and illegible. Some Victorian pillars standing proud and straight but others leaning against one another like end-of-day commuters slumped shoulder to shoulder on the Northern Line.

Hopeful sentiment is engraved here over and over: Never Forgotten; Always in our Thoughts. But you look at relentless climbing nature and wonder how long any of this remembering can really last. Two generations? Three? A bit more, for the famous — but the truth is that they too will “fly forgotten as a dream,” as Isaac Watts has it. Even at George Eliot’s grave, tended lovingly by a woman with gloves and garden tools, the name itself has all but evaporated.

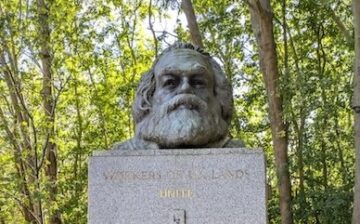

Marx, ten feet tall on his plinth, will last longer than most, but only because of sculptor Laurence Bradshaw’s massive, bombastic, expressionless Great Leader bronze. It seems at once marvelously appropriate and marvelously inappropriate. Lenin would have approved, as so many other followers have. But I was so sure that the resident himself would have been embarrassed by it that I stepped up close and asked his opinion. A low growl resolved itself into a voice. “Funny you should mention Lenin. He always was in the vanguard of aesthetically challenged petit-bourgeois sentimentalism. Can’t stand monuments, personally. Why do I attract people like that?”

Marx, ten feet tall on his plinth, will last longer than most, but only because of sculptor Laurence Bradshaw’s massive, bombastic, expressionless Great Leader bronze. It seems at once marvelously appropriate and marvelously inappropriate. Lenin would have approved, as so many other followers have. But I was so sure that the resident himself would have been embarrassed by it that I stepped up close and asked his opinion. A low growl resolved itself into a voice. “Funny you should mention Lenin. He always was in the vanguard of aesthetically challenged petit-bourgeois sentimentalism. Can’t stand monuments, personally. Why do I attract people like that?”

Certainly not all of them are like that. As we were about to leave, a young woman came by and nearly dropped her phone trying to take a selfie. When I offered to help she thanked me effusively and stood there with a radiant smile that almost dissolved into a giggle as she raised a clenched fist. I captured several angles, wondering whether she had dressed all in red for the occasion. The plinth alone dwarfed her, but her face, unlike the one they’d given Marx, expressed character, depth, and a sense of humor.

Later in the day, across the Heath at Kenwood House, I got to think some more about faces, depth, and memorializing. Upstairs there is a collection of so-called “swagger portraits” representing the (mostly) Jacobean high and mighty in all their finest finery. Lord Thomas Howard de Walden, by an unknown artist, is stereotypical of the genre: a man so randy for prestige that the person has vanished into the clothes. A full and fascinating life, actually, but the portrait is trying far too hard. That collar! That golden chain! That thick knotted cord with its frankly testicular appendages! Everything shrieks of style and money and court influence — except for the ghostly, weak, characterless face. You can’t look at it without wondering whether Howard knew what has been done to him.

Later in the day, across the Heath at Kenwood House, I got to think some more about faces, depth, and memorializing. Upstairs there is a collection of so-called “swagger portraits” representing the (mostly) Jacobean high and mighty in all their finest finery. Lord Thomas Howard de Walden, by an unknown artist, is stereotypical of the genre: a man so randy for prestige that the person has vanished into the clothes. A full and fascinating life, actually, but the portrait is trying far too hard. That collar! That golden chain! That thick knotted cord with its frankly testicular appendages! Everything shrieks of style and money and court influence — except for the ghostly, weak, characterless face. You can’t look at it without wondering whether Howard knew what has been done to him.

English Heritage is currently running a show of these paintings alongside a series of homages, or pastiches, by the artist Stephen Farthing. I like the fact that Farthing has redone Daniel Mytens’s famous portrait of James I without a head at all, the canvas ending at the neck; it makes the point nicely, if a bit bluntly. On the other hand, isn’t the original enough? Imagine a still life of gorgeous, glistening tropical fruit with a single spade-damaged potato at the top: that’s what Mytens has done with poor James’s face. So many of these “swaggers” are already, without modern commentary, revealingly and cruelly self-undermining.

None of this would be quite so obvious, perhaps, except for the fact that when you go downstairs — leaving behind this historically interesting collection of bling, and bling about bling — you encounter a twelve-cylinder anti-swagger masterpiece.

To make a point of saying that Rembrandt’s Self-Portrait with Two Circles is a great painting feels a bit odd, like opining solemnly that the Mona Lisa is a great painting. Too famous, too obvious. But for me the experience of seeing it for real at last, after a thousand reproductions, had the quality of deep aesthetic shock: it is simply and literally breathtaking. Here is the precise geometric opposite of memorializing, of cast bronze pomposity, of swagger. Here the artist’s clothes have been reduced to a nimbus of scumbled brown; his linen cap merely suggested in a few violent slashes of white; his marl stick and brushes made central and dramatic but only by reducing them to four or five diagonal smears that teeter on the edge of nothingness. (How did you do that?)

To make a point of saying that Rembrandt’s Self-Portrait with Two Circles is a great painting feels a bit odd, like opining solemnly that the Mona Lisa is a great painting. Too famous, too obvious. But for me the experience of seeing it for real at last, after a thousand reproductions, had the quality of deep aesthetic shock: it is simply and literally breathtaking. Here is the precise geometric opposite of memorializing, of cast bronze pomposity, of swagger. Here the artist’s clothes have been reduced to a nimbus of scumbled brown; his linen cap merely suggested in a few violent slashes of white; his marl stick and brushes made central and dramatic but only by reducing them to four or five diagonal smears that teeter on the edge of nothingness. (How did you do that?)

And then there’s the face — oh! After a while I had to stand aside and rest my eyes on an empty bit of wall, and I thought of something George Steiner wrote about the kind of experience that motivated him as a critic:

Great works of art pass through us like storm winds, flinging open the doors of perception, pressing upon the architecture of our beliefs with their transforming powers … We seek to record their impact, to put our shaken house in its new order. Through some primary instinct of communion we seek to convey to others the quality and force of our experience. We would persuade them to lay themselves open to it.

Sorry, but I can’t convey it. Marx and Howard should have been so lucky. This face leaves me wordless.