by Carol A Westbrook

In our third year of medical school we began our clinical studies. After two full years of classroom work, it was time to apply what we learned to real patients. One can spend years in the library, reading all the books and journals that you can get your hands on, but there is no substitute for seeing a patient with disease. The stories I’m recounting here are all true, as I experienced at the University of Chicago Hospitals (then called Billings Hospital) while I was a medical student in 1977-78. I’ve changed the patients’ names, and I’ve made up some details I couldn’t recollect.

Billings hospital had a locked psychiatry ward, and it admitted patients for brief interventional stays, with a Medicare limit of two weeks. If a longer stay were required, the patient would have to be transferred to a chronic care facility. Patients could be either voluntary admissions or legally committed.

Psychiatry rotation for a third-year med student was 1 month long, of which 2 weeks were spent on the inpatient service. That was just long enough for the student to admit a patient and follow them through discharge; we each had our own individual patient. We had a four-member team (3 students and one resident) The resident took call every third night, which means they stayed overnight and answered the pager for problems on the ward or in the emergency room. We students were expected to come along. We did not carry our own pagers, but we took orders from our resident, who did carry a pager. Although call requires an overnight stay—with little sleep—it can be one of the most valuable experiences of med school, because that’s when you get to see the extreme cases, the ones you’ll never forget.

THE FOG COMES ON LITTLE CAT FEET

My very first day on service our team was on call. The resident would meet us students on the ward. On our way there the resident’s pager sounded, and it was the ER (emergency room)! The resident tossed the pager to me:

“Dr. Westbrook, go down to the ER and see what they want. I’ll be tied up for a half hour, so see if you can hold the fort until I can get down there.”

I ran down to the ER and was directed to room #4. In the room, a frightened-looking middle-aged woman was standing on a chair, with a terrified look on her face. She was very agitated.

“Help me! Get it away from me! It’s going to kill me!”

I talked slowly and quietly. I asked her name – it was Mae N, and asked her what it the problem.

She quieted down a lot, and told me that the fog was coming for her.

“If it touches me, it will kill me. You have to help me push it away.”

“I’ll do everything I can to help you,” I said. “But you have to tell me more.”

So she began to tell me about this fog, and who could see it (only her), and where it came from. I kept her talking, about her family, her kids, and anything on her mind. She quieted down and we talked for over about 15 minutes so she could describe what was going on.

Then I asked her how to get rid of this fog, and she continued, “they were in my purse, I took one twice a day and that pushed it away, but they are all gone.”

I suddenly realized that she was talking about her medication.

“Were these pills that pushed it away?”

“Yes.”

“When is the last time you took any,” I asked.

“Last week. Then they ran out. I couldn’t get any more because my clinic closed. ”

“May I see the empty bottle?” I asked, and she handed it to me.

I read the label. It was an often-prescribed antipsychotic medication that is used to help people with schizophrenia control their symptoms and lead a normal life. It soon became apparent that Mrs. N was hallucinating because she ran out of medication. When my resident appeared, he ordered a Thorazine injection, started her back on her medication, and admitted her to our ward on 3West. Soon she quieted down and said the fog was receding.

Mrs. N was a classic schizophrenic who was previously well-maintained on antipsychotic medications; stopping her medication precipitated an acute psychosis, manifest as her being threatened by an evil fog. This evil fog was a recurring theme in her hallucinations. Fortunately, she responded well to resuming her medication, avoiding the danger of escalation to a more dangerous condition.

She was back to her normal self soon, and wished to go home. Her family was with her, and reassured us that she managed just fine at home. They could keep an eye on her and call the nurse or bring her in as needed. She was safe to go home and we discharged her to a follow-up appointment at the university clinic.

DON’T LET ANYONE KNOW THAT I’M HERE

“Dr. Westbrook,” my resident said, “You’re up for the next admission. Go down to the ER and meet Mr. Ray G., a 60-year-old retired mail carrier. Do his history and physical and, if appropriate, admit him to our ward in the hospital. I’ll help you write up the orders.”

I quickly headed downstairs to the ER to pick up my admission. Mr. G was in a cubicle with the curtains drawn, pacing impatiently.

“I’m so glad you’re here!” he said, with relief in his voice. “Please take me upstairs as soon as possible, and we can do the history and physical later. The ward is locked, isn’t it? I don’t want anyone to know that I here. I especially don’t want my brother-in-law to find me and spray me with his aerosol can. The spray is fatal. To avoid him, I took the 55th street bus , changed direction, walked a couple of blocks to the South Shore train and walked from the station. I lost him after the 55th street bus, but he’ll soon figure out I’m coming here. So please let’s be careful!”

He cracked the curtains, looked around, peered out at the waiting room, and said, “he’s not here yet. We still have time. But let’s hurry before he spots me, or I’m a goner!”

I took his paranoia seriously, and worked up his admission as quickly as I could. The following day I attended the group therapy session to which Ray had been assigned. Except for his paranoia, Ray appeared to be a perfectly normal 50-year-old man, formerly a mail carrier but now on medical disability. He was friendly, with a good sense of humor; he enjoyed telling his story of being chased by his crazed brother-in-law who was sporting an aerosol can spraying deadly toxins. Ray feared his wife’s brother, and truly believed he was in danger of death at this man’s hands.

During rounds the next day, our attending pointed out that Ray had an uncommon form of schizophrenia, called “paranoid schizophrenia with a fixed delusion.” It was felt to be hard to treat, with a persistent delusion that the patient firmly believes is real. That was in 1978. In 2013, however, the American Psychiatric Association determined that this behavior was just another manifestation of schizophrenia. While the term for thie specific form of schizophrenia is now outsdates, paranoia is still a key symptom that experts look for when diagnosing and treating schizophrenia. He would likely be kept for another week and treated with anti-psychotics until he was safe to go home.

FOR WHOM THE BELL TOLLS

Mauve B. was a woman of about 50. Her family said that she had a long history of depression and had been on medications on and off over the years, but was never hospitalized for it. Recently she had been changed to a different medication, and within a week she began hallucinating, losing touch with reality. She was talking, but not to anyone we could see, and she didn’t talk to any of us. As we listened, she appeared to be at a funeral. Her own funeral. She was wide-eyed, looking at a distant sight and trying to get out of the guerney. It was necessary to hold her down with restraints.

“Do you hear those bells? I hear them. They are tolling for me. I must go. They want me dead. I have a knife and I’ll kill myself. Sweet Jesus, I am coming. Send your angels to carry me into your arms! I am ready to die, the world has no use for me,” she said, as she reached out to the sky with open arms. You could almost believe she was looking into the afterlife, perhaps into heaven. It was dramatic and compelling, but also frightening.

Her husband worried that she would try to kill herself, and wanted to bring her to safety. He called an ambulance to take her to the ER. At first, she cooperated, but then she became disoriented and combative. She kept trying to leave the car to “reach up to the angels.” By the time they got to the ER, it took two people to restrain her. She was given an injection of an antipsychotic medication, and admitted to the hospital ward under close supervision, with a suicide watch in place.

She calmed down, returning to normal behavior in a day or two. During group session she explained that she had been depressed recently. Both of her sons had gone off to college, leaving her an “empty nester.” Coincidentally she was also going through menopause. Her anti-depressive medication was changed to something stronger, and that’s when she became suicidal; soon her hallucinations began. After two week of intensive therapy she returned to normal, and was discharged home.

Several months later I was on the Chest service. Chest was a throwback to the old days of tuberculosis. Now it was mostly asthmatics and chronic lung disease. I was paged for a new admission, and was I surprised to see Mauve. She had tried to kill herself by stabbing her chest with an ice pick! She had collapsed a lung and was brought by ambulance to the ER, where she was admitted to the surgery service for chest tube placement. The chest tube will help reinflate her lung and allow her to breathe. Her psychiatric condition was stabilized with medication, and she was transferred to the chest service for recuperation.

“Why Dr. Westbrook, what a pleasure to see you again! “

“What a surprise, Mrs. Mauve. What happened?” I asked.

She told me about the stabbing but regretted it; she did not feel suicidal anymore. “And I’m sure we’ll have a good time together!” she said. I reassured her that we would.

When she first presented, it was difficult to tell if Mrs. Mauve had schizophrenia or severed depression. Major depressive disorder with psychosis may cause symptoms including hallucinations or delusions during a depressive episode. It is a dangerous condition because the patient may have side effects from exhaustion as well as the risk of suicide. Treatment is usually medical, and the prognosis is good.

ONE OF OUR OWN

Psychiatry rotation ended, and I moved on to Internal Medicine. Dr. L was the attending physician on our 3-student team. He was well-known to be one of the best clinical teachers in the school—and one of the most demanding. We had patient rounds with the resident at 7 am every day, and teaching round with Dr L at 10 am, during which we presented our patients and analyzed their medical problems. Each student followed 5 to 9 patients, and call was every third night. It was a grueling service; at night, we students had to keep up with reading books and journal articles about our patients’ conditiond in order to be prepared for attending rounds the next morning. We were stressed and sleep-deprived.

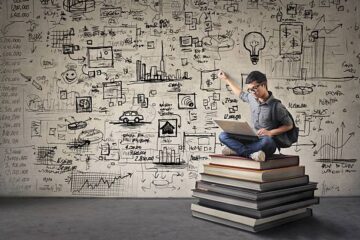

This is the price we had to pay for having Dr. L. as our teacher, and it was well worth the effort. He would analyze one of our patients, standing next to the whiteboard with marker in hand, drawing diagrams and arrows to show interconnections between the organ systems and how they led to the diagnosis; it showed where medication effected treatment—it was a beautiful, almost poetic experience.

Our second day on service our team was on call. We were all up late, doing the history and physical, examining the newly-admitted patients, writing our notes, and going to the residents’ library to find articles about the diseases. Thomas, one of the students (not his real name) was especially enthusiastic. At about 11 pm he came back to our workroom with a huge pile of xeroxed articles and journals that he could barely carry. He started scanning them and talking continuously to all of us about the diseases and how they were interconnected. He began to write on the whiteboard and soon it was covered with symbols. His talking began to get wilder and wilder as he pointed out connections and his new discoveries—almost a parody of Dr. L. We were impressed with his research and deep understanding.

Tom was still going strong at 4 am; the rest of us went to our call rooms to catch a few winks, knowing we had to be up and ready for rounds in 3 hours.

Tom did not show up for rounds that day, and he was not in the call rooms. We split up the work on his patients and got through our morning chores. At 10:00 attending rounds Dr. L showed up.

“I’m sorry, “Dr. L. said to our assembled team. “Your colleague, Dr. Thomas, will not be coming back to this service. At present he is hospitalized. As you have probably realized, he is having a manic attack, probably brought on by stress and sleep deprivation, possibly on top of an underlying manic-depressive condition.”

The two of us med students looked at each other, in shock. We were horrified that we didn’t recognize Tom’s unusual behavior for what it was—a manic episode! We should have known better!

We didn’t see Tom anymore that semester, nor for the rest of medical school. I didn’t keep in touch, but saw him again at our 30th reunion. We shook hands and then hugged. Thomas seemed pretty normal. He did, in fact graduate from our medical school with our class, and was now in private practice in internal medicine. He introduced his wife, and bragged about his 3 children. I shook his hand again, said goodbye, and wished him well; I didn’t ask after his manic-depression, but I suspect it was now a thing of the past.

For the four years of med school we learned about diseases from lectures, books, and journal articles, but most importantly from our patients. One can spend years in the library reading all the material you can find, but there is no substitute for seeing a patient with the disease, and this is why being on call is so valuable. This is especially true of psychiatric disorders. It is hard to imagine what it is like to be schizophrenic and hallucinating until you meet a person who will tell you what it’s like, the fear, apprehension, and disorientation that they feel. I am grateful that we can help them cope and return to a normal life.