by Mark Harvey

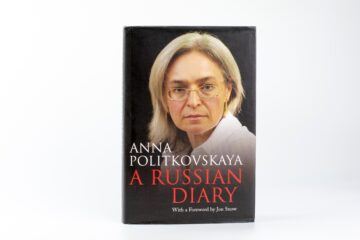

On September 1, 2004, a middle-aged Russian journalist named Anna Politkovskaya boarded a plane in Moscow on her way to Ossetia to cover a hostage crisis in the town of Beslan. During the flight, she drank a cup of tea that almost killed her. After she drank the tea, she became disoriented, began to vomit, and ultimately lost consciousness. She was taken to a hospital in Rostov-on-Don, where doctors concluded she had been poisoned.

Politkovskaya had been reporting on the human rights abuses in Russia and Chechnya for some time and was a harsh critic of Vladimir Putin. In one of her books she had written, “If you live in Russia, you cannot help but notice that Putin’s Russia is a world of violence, lies, and injustice.”

Throughout her career, Politkovskaya received death threats and was heavily surveilled by the Russian government. But the intimidation didn’t stop her, and she wrote hundreds of articles for the independent newspaper Novaya Gazeta and several books highly critical of Putin. In her 2004 book, Putin’s Russia, she bravely wrote about the corruption, human rights abuses, and oligarchy in Russia with an unflinching style.

In short, she was a daring, hardworking investigative journalist who risked her life to write about the cruel and criminal aspects of Russia. She was assassinated in the elevator of her apartment building on October 7, 2006—Vladimir Putin’s birthday.

Politkovskaya’s story is a moving example of the commitment of the best journalists. Unfortunately, the circumstances of her assassination are nothing new or even unusual. Journalists from Sri Lanka to Mexico have been assassinated because of their relentless efforts to bring out the truth. Veronica Guerin, an Irish journalist born at about the same time as Politkovskaya, dedicated the later years of her career to writing about the drug trade in Dublin. She, too, wrote fearlessly about some of the most dangerous men in the world, even interviewing some of them for her investigations.

The first attempt on Politkovskaya’s life was a poisoned cup of tea; Guerin’s was being shot in the leg by a masked man in January 1995. It didn’t stop her courageous journalism and she continued to write until the end of her life when she was assassinated by two gunmen on a motorcycle in 1996.

Fortunately, we don’t have many outright assassinations of investigative journalists in the United States. And we’ve had some great journalists who have brought down presidents, uncovered corporate scams, written about drug cartels (even if those cartels are registered corporations selling opioids), and chased serial killers. But there are few occupations more reviled by MAGATS than journalism. It doesn’t matter how carefully an article is researched, sourced, and fact-checked: if the piece challenges one of their ilk or their ideas, they trot out their favorite shibboleth, “Fake News.” But the free press—the hardworking, resourceful, and fully funded investigative journalists—are one of the institutions keeping our democracy from totally blowing apart.

The First Amendment in our Bill of Rights guarantees a free press, but the idea and defense of a free press came many years before the writing of our Constitution. Some credit the poet John Milton, author of Paradise Lost, for the early defense of a free press. Twenty-three years before he wrote his 80,000-word blank verse poem about the struggle between God and the Devil, Milton wrote Areopagitica, a pamphlet on the importance of the right to freely express ideas, good ones and bad ones. The British critic Christopher Ricks wrote, “Milton is a poet who wrote as though he’d just remembered the invention of words, and was determined to use every one of them.” But Areopagitica was one of the few works where Milton was concise: it was only 30 pages long.

Milton wrote Areopagitica in 1644 during the English Civil War, more than a hundred years before the American Revolution. It’s said that he wrote the pamphlet in protest of the cruel treatment of “Freeborn John” Lilburne, a political activist and sometime printer. When Lilburne printed and circulated unlicensed books, he was tried and convicted for violating the Licensing Order of 1643, essentially a law requiring anything that was printed to be approved by the monarchy. For his refusal to obey the laws of censorship, Freeborn John was tied to an oxcart at Fleet Prison, stripped of his shirt, and then flogged with a three-thonged whip as he was dragged the two miles to Westminster. He received as many as 500 lashes on the journey. At Westminster, he was pilloried. Even stooped in the pillory, Lilburne continued to rail against censorship until the government gagged him and put him in prison.

Milton himself had been censored for one of his writings defending divorce, which was considered heretical at the time. So he took Lilburne’s punishment to heart. Milton was a deeply religious Puritan so there is some irony in his being a great defender of unfettered speech and writing, given the Puritanical flavor of censorship in America today. But Milton invoked God to defend freedom of speech and the press. In one passage in Aereopagitica, he wrote,

For who knows not that Truth is strong, next to the Almighty; she needs no policies, nor stratagems, nor licensings to make her victorious; those are the shifts and the defenses that error uses against her power.

He believed that human beings had a God-given ability to discern the truth and that it would do them no harm to read near everything under the sun. He even believed that reading false manifestos could be good for a person’s education, writing, “Let Truth and Falsehood grapple; who ever knew Truth put to the worse, in a free and open encounter?”

Close to a hundred years later on the far shores of America, Ben Franklin defended freedom of the press with the same vigor as Milton in his 1731 essay, Apology for Printers. He wrote,

Printers are educated in the Belief that when Men differ in Opinion, both Sides ought equally to have the Advantage of being heard by the Publick; and that when Truth and Error have fair Play, the former is always an overmatch for the latter.

It’s impossible to know if Franklin read Aereopagitica, but he had the same spirit of Milton in challenging the oppressive British crown. Combined with his writing and the power of his press, Franklin challenged the British colonial rule long before the American Revolution and he challenged slavery long before the Emancipation Proclamation. Though 37 years his elder, Franklin worked with Thomas Jefferson in writing The Declaration of Independence and, it must be assumed, influenced Jefferson in his vehement belief in a strong press.

Jefferson was the founding’s strongest advocate for the media. He wrote, “Were it left to me to decide whether we should have a government without newspapers, or newspapers without a government, I should not hesitate a moment to prefer the latter.”

Edmund Burke is credited with naming the media the Fourth Estate. The first three estates were the clergy, nobility, and House of Commons. In France, the media is called le quatrième pouvoir, which means the fourth power after the executive, legislative, and judiciary.

Call it what you will, but the meta quality of good investigative reporting acts as a sort of critic and conscience for societies and nations. There are plenty of magazines, television shows, blogs, and the like that aren’t worth the pulp or pixels they’re printed on. But the courageous journalists and publishers with the same courage as Anna Politkovskaya, Veronica Guerin, Freeborn John Lilburne, or Ben Franklin have moved us forward and, at times, kept us from reverting to a near feudal mindsets. Most journalists are underpaid and overworked. The good ones spend long hours poring over public documents, burning shoe leather to chase down leads, bear the abuse heaped on them, and go out to do it another day.

In America, they have exposed the inhumanity of slavery, the abuse of child labor, vast government coverups, the dumping of toxic waste into rivers, lethal defects in automobiles, spy rings, pedophiles among the clergy, and more.

Newsrooms in America have been gutted over the last twenty years, and more than 2,000 newspapers have been shuttered in that time. This has left many communities without a local news source and led to what is being called “news deserts.” The lack of local news leads to more government corruption, poor policy decisions, less cohesion within a community, and often the consumption and spread of conspiracy theories.

The demise of American news sources is due to ad revenue stolen by digital behemoths like Google and Facebook as well as the consolidation of small papers under huge corporations. It’s an unhealthy combination that has vastly weakened the fourth estate.

But out of all this there is an encouraging turn to independent, non-profit investigative reporting. Perhaps the most glorious example of this trend is an organization called ProPublica. It’s a long way from Westminster, where Freeborn John was pilloried and gagged several hundred years ago, to the office of ProPublica in New York City. But there is a long trail of brave men and women who have suffered prison and torture and even lost their lives on the path to the birth of one of the world’s great investigative reporting operations in 2007. In its relatively short existence, ProPublica has won seven Pulitzer prizes, numerous Peabody Awards, George Polk Awards, and even Emmys for its in-depth reporting.

Few Americans know what ProPublica is and it certainly doesn’t have the millions of readers of, say, The New York Times. But ProPublica stories are constantly being picked up by the huge media outlets and then either shared verbatim, copied, or used as springboards to further report on an issue. It’s ProPublica that exposed the loopholes in our tax system that allow billionaires like Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk to pay little income tax. It exposed how poorly The Red Cross managed its money and resources during major disasters such as Hurricane Sandy. It exposed the poor response of law enforcement during the Uvalde massacre in Texas. In a series called “Dollars for Docs” ProPublica uncovered the coordinated efforts of huge drug companies to pay doctors to prescribe their drugs. These are just a few examples of what this non-profit news organization does.

All across the country there are other examples of independent investigative news organizations emulating ProPublica. In Montana, The Montana Free Press has done excellent reporting on the relationship between wildfires and climate change. The Mississippi Today reported the gross misuse of tens of millions of dollars of funds meant for families in need to build things like university volleyball courts and to pay Brett Favre over a million dollars for speeches he allegedly never gave. Aspen Journalism has reported extensively on water grabs in western Colorado and toxic spills into pristine rivers. The Texas Tribune uncovered the failure of the Electric Reliability Council of Texas to anticipate and prepare for the great power failure of 2021 that left millions of Texans without power.

All across the country there are other examples of independent investigative news organizations emulating ProPublica. In Montana, The Montana Free Press has done excellent reporting on the relationship between wildfires and climate change. The Mississippi Today reported the gross misuse of tens of millions of dollars of funds meant for families in need to build things like university volleyball courts and to pay Brett Favre over a million dollars for speeches he allegedly never gave. Aspen Journalism has reported extensively on water grabs in western Colorado and toxic spills into pristine rivers. The Texas Tribune uncovered the failure of the Electric Reliability Council of Texas to anticipate and prepare for the great power failure of 2021 that left millions of Texans without power.

The Institute for Nonprofit News (INN) reports that it has more than 350 nonprofit news organization members today, nearly four times its membership in 2010. I think this is a most encouraging trend. Strong, in-depth, fearless journalism is not only what makes America great––it is what makes America good.