by Mark R. DeLong

Once a real irritant and frustration, the routine has become a slap-stick show staged in our living room. Today, it’s only slightly tinged with impatience. Someone wants to watch a movie, which is a challenge itself, since that means having to find one worth watching. But there are lists, online reviews, thumbs-up (and down) from friends, and Rotten Tomatoes flung (or not) and Metacritic. You make a guess. You land on a title, and that’s when you engage The Bureaucracy. From that point on, your smartphone’s glass screen no longer stays your own. The flat and wide display across the room becomes possessed by something else—just as you agreed would be the case back when you clicked “I agree” on the annoying “End User License Agreement.” You never read it. You’re in good company; no one reads the “EULA.” The run-up to the show is, well, a ping-pong of passwords, a inchoate suspicion or hope that the app you’re using will actually connect to … to … something that will “cast” your movie to the display.

“Cast” is a word loaded with magical innuendo, word of spells and the luck of fishing.

I like to think that the rituals of my devices somehow unite a community—in my case, I guess, a community of Android phone users who dangle Google-provided services through a Chromecast dongle that hangs limply from the edge of an ancient plasma flat-screen. But unlike ritual’s usual rigidity, the technological rituals mystify with nuance; they follow subtly different paths, so you never really learn the trail by heart. (And, it’s not just Google in the priestly robes waving the thurible.)

Half of the adventure of watching a movie at home is just getting to sound and picture.

Product v. Bureaucracy?

Beyond a certain age, a writer attempting a comparison/contrast description is beset with the danger of becoming sappily nostalgic or, worse, bitter—an “Old,” muttering curses, clenched fist, body taking the shape of a complaint. Clare Coffey comes close to that in her entertaining essay, “Things Use to Work in This Country“—the title itself invokes the nostalgic and has probably been uttered at one time or another by a significant segment of the Boomer population. Coffey admits to a bit of nostalgia, but she also points to a state of things: “Things use to, literally, work.”

But when I say “things used to work,” the object of inherited nostalgia is not only manufacturing standards before planned obsolescence and offshoring. Things used to, literally, work. You turned a knob, and sound came on, because the knob controlled the mechanism that tuned the radio to the broadcast that the big metal radio towers dotting the landscape beamed at you. I am not a gearhead of any description and don’t care much about how the insides of electrical devices work, but I know exactly what I, personally, have to do to operate my end of the GE radio. There are no downloads, no platforms, no passwords, no little pull-down menus, no verifications or account recovery protocols. There is no streaming. Personal technology used to be a machine. Now it’s a bureaucracy.

The essay is mainly a lament, though it also praises an old product. “Personal technologies” like Coffey’s beloved radio relied on its mechanical and internally complete qualities. In the case of her P2940A Model General Electric “World Monitor,” the product was an endpoint, invisible to “upstream” radio transmission infrastructure. Certainly, it benefitted from the “bureaucracy” that radio infrastructure implied (think: FCC, station licensing, programming, antennae, physical infrastructure), but the old radio, in the United States at least, didn’t apparently participate in the bureaucracy. It just consumed the benefits of the bureaucracy.[1]

Coffey is right when she claims that products have increasingly become parts of a “bureaucracy.” The term “personal technology” has become ambiguous, or perhaps more accurately, it doesn’t apply in the same way as it did when Clare Coffey’s family radio was new.

What’s important to note is that Coffey’s description conveys the sense of control and mastery that she feels with the products of fifty years ago. That practical control, though, has noticeably slipped from the consumer’s grasp, especially in the last decade. Even in 1984, when Coffey had already listened to her GE radio for about a decade, Christopher Lasch observed, “The consumer feels that he lives in a world that defies practical understanding and control, a world of giant bureaucracies, ‘information overload,’ and complex, interlocking technological systems vulnerable to sudden breakdown.” He cited the failure of the power grid in Northeast U.S. and the near meltdown of the Three Mile Island nuclear power plant as examples of paralyzing and incomprehensible breakdowns (to consumers, at least, if not to engineers).

Coffey’s essay points to an apparent faltering of “practical understanding and control” of devices, a slippage occasioned in part by a fuzzification of the border separating a physical product (a GE radio) and “services” that a device delivers—services that require continuing transactions and persistent relationships with “providers.” Breakdowns of devices no longer require a near catastrophe. A lost password will do, a bug, a device “compromise,” some minuscule device flaw, or just a human desire to have some time away from prying digital eyes.

We should view those bureaucratic elements of new products as the product itself, something that is in some curious, even perverse, way part of a package we “own.” Really, even ownership seems to be called into question by some modern (say, post-2010) personal technology—maybe even a lot of it—since it gathers and claims ownership of personal information about us. Unlike Coffey’s radio, devices see us in their digital bureaucratic way, often in order to direct us and, especially, our purchases.

Ties that continually bind

Consider the Tesla vehicle in your neighbor’s driveway. It has the appearance of a car not that unlike what your father had, but its workings and the car’s service feel, well, more diffuse. The car comes with strings attached, and they make the experience of ownership an abiding agreement, more a tether than a hand-off at the edge of a car lot. You have to consent to this relationship, too. The modern Tesla has features that allow the company to keep tabs on the vehicle which, the company says, have the effect of “allowing for advanced features and an enhanced driving experience.” But Tesla lets customers choose not to have their car connected: “However, if you no longer wish for us to collect vehicle data or any other data from your Tesla vehicle, please contact us to deactivate connectivity…. If you choose to opt out of vehicle data collection (with the exception of in-car Data Sharing preferences), we will not be able to know or notify you of issues applicable to your vehicle in real time. This may result in your vehicle suffering from reduced functionality, serious damage, or inoperability” (my emphasis). Aside from the rhetoric of that last sentence, which certainly raises alarm bells and pushes car buyers toward consent, the statement highlights the notion of the machine as a “bureaucracy.”

“So, uh, just sign here, please.”

Or consider that new humongous flat-screen TV you saw at Costco. It’s likely just as able to watch you as you are able to watch it—and for good business reasons. Television manufacturers have discovered that advertising and viewer data revenues are so significant that Vizio, for example, saw a dramatic inversion in sources of profits between 2020 and 2022. Industry analysts at Omdia show that in the first quarter of 2020, Vizio traced $49 million of its profit to hardware and $9 million to “platform services” which include advertising and viewer data services. By fourth quarter 2022, that balance had reversed, with $89 million credited to “platform services” and a scant $3 million to hardware. (In the first quarter of 2024, Vizio reported a loss of $7.2 million on hardware but made up a $88.3 win on services.) Ars Technica‘s Scharon Harding reported that GroupM found that the steep growth in “services” is likely to continue for the industry as a whole: “smart TV ad revenue grew 20 percent from 2023 to 2024 and will grow another 20 percent to reach $46 billion next year,” Harding wrote.

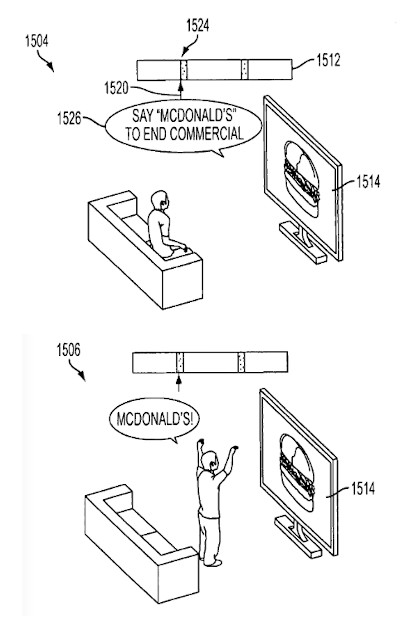

New TVs increasingly include “automatic content recognition” (ACR) which allows the TV manufacturers to learn what you’re watching, whether it’s streamed, or a local station broadcast, or your own DVD run on a device in your media cabinet. Many televisions are fitted with cameras and microphones, too, “for Zoom calls.” A newcomer TV company, Telly, offers “the smartest TV at the revolutionary price of free.” The low, low price comes with surveillance and advertisements attached, since Telly customers exchange data and certain use restrictions for the 4K devices. In addition to survey data collected on sign up, Telly gets personal information goodies after the television is installed, including TV settings, usage, searches, and “how many people are within 25 feet of the TV,” Harding noted.

Though television manufacturers disclose such bureaucratic surveillance features to purchasers, as Harding wrote, “there are plenty who don’t know the extent to which their TVs are monitoring them. Complexity in understanding and controlling TV tracking is especially relevant as more sets incorporate microphones and cameras. Terms of service are often complex, wordy agreements buried in elusive TV settings or online, and companies have ways of strong-arming TV owners into accepting such agreements. Further complicating matters, it’s possible for consumers to disable tracking from the TV OS provider, such as Google, but still be tracked by the TV OEM, like TCL.”

Of course, there is an upside to having a television watch over you: You’ll never watch a movie alone.

After the movie, it’s time for bed. In 2019, Shoshana Zuboff pointed out a “rendition” of data that Sleep Number beds accomplish. In exchange for the bed’s and its app’s features, the company says that bed collects “biometric and sleep-related data about how You, a Child, and any person that uses the bed slept, such as that person’s movement, positions, respirations, and heart rate.” The bed “collects all the audio signals in your bedroom.” (Presumably, the company could extrapolate other activities that take place.) All of this data is sharable with third parties, and might be used for advertising, and the company notes that can take place “after You deactivate or cancel the Services and/or your SleepNumber account or User Profile(s).”

So, as is the case with watching television, you’ll never sleep alone in your bed.

Cars, televisions, beds, and a host of other products—in a perverse way, they are all working very, very well in this country. Their features go well beyond those of, say, Coffey’s GE radio and reach so deeply into your life that the old chestnut “You’re not the customer; you’re the product” seems rather quaint. Of course, many have wondered whether their refrigerator, washing machine, or oven really need to be connected to the Internet or paired with their phones.

How many have actually decided not to purchase devices designed to be invisible roommates who report to some remote commercial bureaucracy?

[1] Before 1971, Coffey’s radio would have been licensed and taxed in the UK, where televisions are still taxed (color: £169.50, black-and-white: £57.00), and so made visible to a governmental bureaucracy.

For the bibliographically curious: Coffey, Clare. “Things Used to Work in This Country.” The New Atlantis 75, no. Winter 2024 (2024): 86–89; https://www.thenewatlantis.com/publications/things-used-to-work-in-this-country. The phrase is much older than Facebook and older than the Internet: “You’re Not the Customer; You’re the Product,” Quote Investigator, July 16, 2017. https://quoteinvestigator.com/2017/07/16/product/. The Telecommunications Act of 2003 (UK; https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2003/21/contents) lays out a bureaucratic infrastructure for broadcasting, which includes a licensing requirement for televisions. Such a tax has been a feature since the Wireless Telegraphy Act of 1904 (now repealed). Jen Caltrider, Misha Rykov, and Zoë MacDonald looked at car manufacturers’ privacy policies and determined that “It’s Official: Cars Are the Worst Product Category We Have Ever Reviewed for Privacy” *Privacy Not Included: A Buyer’s Guide for Connected Products. Mozilla Foundation, September 6, 2023. https://foundation.mozilla.org/en/privacynotincluded/articles/its-official-cars-are-the-worst-product-category-we-have-ever-reviewed-for-privacy/. A good article from Ars Technica: Harding, Scharon. “Your TV Set Has Become a Digital Billboard. And It’s Only Getting Worse.” Ars Technica, August 19, 2024. https://arstechnica.com/gadgets/2024/08/tv-industrys-ads-tracking-obsession-is-turning-your-living-room-into-a-store/. Zuboff, Shoshana. The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power. London: Profile Books, 2019.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.