by Andrea Scrima

Sometimes it’s a single detail that hits home: a little girl’s pink shoe, for instance, with remnants of the delicate fabric still intact, unearthed among the hundreds of worn-down shoe soles and other objects found in the course of an archaeological excavation on the grounds of the former Liebenau camp in Graz, Austria. The site has since been paved over, covered in large part by housing settlements and a youth center, kindergarten, and sports field. The tour guides’ voices could barely be heard above the basketball game underway on a nearby court; in this vibrant residential neighborhood of Grünanger, the loud cries and laughter of everyday life suddenly seemed jarring and alien.

“Resettlement Camp V” was founded in 1940 for “Volksdeutsche” or ethnic Germans, who were relocated from the Baltic states and other parts of Europe and the Soviet Union, often involuntarily. It consisted of 190 barracks built to accommodate 5,000 inhabitants. A year later, as the war raged on, forced laborers and prisoners of war were brought here to toil under unimaginably harsh conditions in the nearby Steyr-Daimler-Puch works, which manufactured machine parts for the armaments industry. In April of 1945, the camp became a temporary stopover for Hungarian Jews on a two-hundred-mile-long death march to the Mauthausen concentration camp after the “Southeast Wall” they’d been building, Hitler’s defensive strategy of anti-tank trenches and fortifications intended to halt the advance of the Red Army along the Hungarian border, failed and they were “evacuated.” Over a period of several days, six to seven thousand exhausted and severely undernourished slave laborers arrived on foot. They had already been on the road for a week and had been given nearly nothing to eat; in Graz-Liebenau they were forced to sleep outside, on the bare ground. They received a bowl of watery soup and a single slice of bread. Those who were too sick or weak to continue were forced to lie face down in shallow trenches, where they were shot from behind, in the neck.

In May of 1947, the British occupying forces had the mass graves exhumed. A trial, verdicts, and executions followed. After that, the matter was repressed and forgotten. More than sixty years would pass before historians began investigating the site in earnest; some of the older locals still knew where the buildings once stood. A series of excavations undertaken during the construction of a power plant uncovered rubble and building foundations, personal belongings, and human remains bearing evidence of war crimes. Already a politically sensitive issue, the area became a point of contention; it was eventually declared an archaeological site requiring the oversight of specialists during any future construction projects or excavations.

The tour of the Liebenau camp was intended as a prelude to a theater performance, but the weather proved uncooperative: taking our seats on benches arranged around the open-air stage, there came a cloudburst so sudden and dramatic that it felt like a logical reaction to the devastation and destruction we had been contemplating moments before. We ran for cover; the rain was pelting down at angles that rendered our umbrellas superfluous. As I made my way home in the storm, I wondered if history is ever past, or if we’ve ever properly understood the factors that can lead to fascism and genocide. Studies in human psychology have shown us that, under certain circumstances, ordinary people are capable of committing horrific crimes and then going home to their families and kissing their children good-night—yet we continue to see these crimes and their perpetrators in terms of good and evil, black and white. Are we certain that horrors of this scale can “never happen again”? As one schoolboy said in a film about the history of the Liebenau camp in his pre-pubescent voice: “You should prepare yourself for everything that comes, regardless of whether you think it’s over with or not [. . .] Even if you don’t believe that someone like Hitler can ever come to power again—now, today—it could always happen, and so you have to understand what happened before and know what you have to do.”

~

Sometime later, I opened the laptop, clicked on the Mail icon, and found a newsletter in my inbox with a headline announcing that Israeli forces had surrounded Khan Younis. Above the headline was a photograph of an Israeli soldier in full military gear standing in the ruins of an abandoned apartment. He was adjusting something on his weapon; in the background were walls pockmarked by mortar shells and machine-gun fire, crumbling concrete, a blown-out window. The walls were painted pink. To the right of the window was a wardrobe with one of its doors hanging open; inside it were neatly folded garments in various shades of pink: girl’s clothing, incongruously intact. Behind the soldier, above a dresser whose drawers had been yanked out and emptied, was a shattered mirror, decorated, like the wardrobe, in pink stripes and a silver-colored floral pattern. In the mirror’s remaining shards, I could just about make out a bed and, when I turned the laptop on its side, a doll lying on its back. Was the girl alive, I wondered, did she flee and where to, and how could it be that the newspaper was using this image—a soldier in a young girl’s pink bedroom—without noticing that it was not the soldier, but the girl’s absence and abandoned doll that were the photograph’s more immediate story? She wasn’t merely absent from the picture—she didn’t exist, she’d been erased without commentary, disappeared into the “but” that was inevitably pronounced when anyone attempted to address or assert her basic right to live.

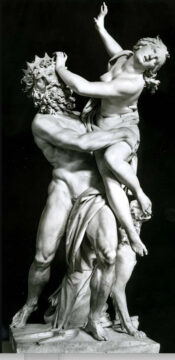

Yes, the civilians, the women and children—but. Yes, the many thousands dead—but. To declare an entire population to be a collective human shield and to claim an absence of other options is to dehumanize the population, regard it as a tool of warfare and hence a legitimate target. I tried to imagine the tunnels underground, with the weight of untold tons of rubble above; tried to imagine the ongoing devastation, the mortar shells exploding overhead and reverberating many yards below through the earth and stone. I thought of the myths of the underworld, of Hades, Charon, and Persephone, who moved between spheres; I pondered an inverted reality in which Hell is above ground and safety far, far below.

I was on a fellowship in Graz, Austria for nearly a year and had been closely following the news in Germany, where I usually live and where it had become nearly impossible to express empathy for the suffering civilians of Gaza without facing outrage and risking serious professional consequences. It had, in fact, become impermissible to even think several complex, contradictory truths simultaneously—the horror of the atrocities committed by Hamas; the displacement of two million people and the thousands of innocents who had died and would continue to die; Israel’s right to defend itself in a perilous region; the undeniable fact of genocide. The United Nations Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Occupied Palestinian Territory had declared Israel guilty of war crimes; the International Court of Justice had ruled that its continued presence in all occupied Palestinian territories was unlawful. Germany, a perpetrator nation, seemed unable to process these basic facts: after decades of “Aufarbeitung” and “Vergangenheitsbewältigung,” the country’s painful and painstaking process of coming to terms with its Nazi past, Germans believed that they’d so successfully absolved themselves of the guilt of the Holocaust that they felt justified in instructing even their own progressive Jewish citizens on the finer points of antisemitism. Angela Merkel once declared that German “Staatsräson”—often falsely translated as the state’s “reason for existence” but more accurately, if profanely, described as the interests of the German state—was linked to its continued support of Israel. Although it went without saying that this support must be contingent on whether or not the country abided by international law, it is now widely regarded as an absolute and has taken on an almost sacred aura. It’s become, in other words, a taboo, and there is no longer any room for discussion—another example of black-and-white thinking, of either/or, although we should know, by now, that there is no unequivocal truth in a situation as ruthless, complex, and intractable as the unfolding tragedy in Israel and the Palestinian territories.

~

In a short story by Swiss author and dramatist Friedrich Dürrenmatt, a student known only as the “twenty-four-year-old” complains to a train conductor that they’ve already been traveling through a tunnel for twenty-five minutes, although the tunnel on the route to Zurich is far shorter. He’s sure of this—after all, he knows the route, takes it back and forth every week. Through an ever-narrowing opening in the rock, the locomotive is hurtling into the darkness at breakneck speed. Searching for an explanation to their alarming dilemma, the conductor and the twenty-four-year-old find a storage compartment, where they climb over piles of suitcases, bicycles, and prams and, after considerable difficulty, finally reach the engine room. They can barely hear each other’s voices above the terrible din. The twenty-four-year-old wants to know whether they shouldn’t finally pull the emergency brake. The conductor, whose name happens to be “Keller” or “cellar” in English, hits a few buttons and switches and pulls the brake—but the massive locomotive fails to obey and races on into the darkness ahead.

In a short story by Swiss author and dramatist Friedrich Dürrenmatt, a student known only as the “twenty-four-year-old” complains to a train conductor that they’ve already been traveling through a tunnel for twenty-five minutes, although the tunnel on the route to Zurich is far shorter. He’s sure of this—after all, he knows the route, takes it back and forth every week. Through an ever-narrowing opening in the rock, the locomotive is hurtling into the darkness at breakneck speed. Searching for an explanation to their alarming dilemma, the conductor and the twenty-four-year-old find a storage compartment, where they climb over piles of suitcases, bicycles, and prams and, after considerable difficulty, finally reach the engine room. They can barely hear each other’s voices above the terrible din. The twenty-four-year-old wants to know whether they shouldn’t finally pull the emergency brake. The conductor, whose name happens to be “Keller” or “cellar” in English, hits a few buttons and switches and pulls the brake—but the massive locomotive fails to obey and races on into the darkness ahead.

During World War II, it took a year and a half to construct the four-mile-long tunnel system inside the mountain at the center of Graz, which branches out in an intricate network of interconnected shafts and caves. During the many days and nights the city was pummeled by bombing raids, a large part of the city’s population found shelter in the Schlossberg tunnels, built by forced laborers and prisoners of war from Poland, Yugoslavia, and Russia. Referred to as “Slavic subhumans” and treated far worse than their Western European counterparts, they’d had to dig out and haul away hundreds of thousands of tons of stone; when the city was under siege, they were forbidden to seek refuge inside the mountain and had to scramble for shelter in the streets amid the shelling. On Easter Sunday of 1945, when the air raids on Graz’s infrastructure reached a pitch of intensity, the railway tracks and tram lines around the main train station were badly damaged, as was the station itself. There are no statistics on the day’s civilian casualties, or how many of these were unprotected “subhumans.” Eight decades later, sitting at my desk in the Cerrini Schlössl on the southern slope of the Schlossberg, I thought about how the basic structures of dehumanization, of human tunnel vision, hadn’t really changed much since that time.

In the ancient Greek myth of Pandora, daughter of Erechtheus of Athens, the human race is denied hope. It’s the last thing left after all the evils of the world have escaped the box Pandora, predecessor to curious Eve, was warned against opening. Christianity, as we know, is a patchwork religion stitched together from the reinterpretations of older pagan myths, and many of its holy days evolved from these stories. It’s often been claimed that Easter’s great miracle was to offer the prospect of rebirth and redemption in place of the hopelessness of antiquity, yet in one of the oldest myths known to humankind, Persephone, who was forced to descend into the darkness of the underworld to meet her kidnapper Hades each year, never failed to return in light and hope with the arrival of each new spring. These are similar, albeit competing stories, yet their original purpose was the same: to help humans understand and accept the inevitability of death, and to celebrate the promise of some kind of existence beyond it or to embrace eternity in the form of life’s recurrent rhythms.

Dürrenmatt’s story picks at the crack between the world we know and the world to come. When fear and misfortune suddenly arrive on an otherwise mundane afternoon on a commuter train, his characters struggle to comprehend the reality of the impending catastrophe. In response to the conductor’s desperate question, “What are we to do?,” the twenty-four-year-old answers: “Nothing. [. . .] God has abandoned us, and so we’re falling towards him.” In this closing line, which fundamentally alters the story and shifts at least one layer of interpretation to the theological, Dürrenmatt seems to be asking whether our imminent end is God’s punishment or part of the unfathomable wisdom of His divine plan. Interestingly, in an edited version from the year 1978, Dürrenmatt left out this final sentence entirely, presenting the dilemma of mortality as an existential, and not a religious, battle taking place in the subterranean regions of the psyche.

~

Just as a theological interpretation changes the meaning of Dürrenmatt’s story, a religious framework fundamentally changes a war narrative and reshuffles the parameters of moral judgment. God is invoked as a blank check; acts are justified that should normally be subject to legal and ethical scrutiny. An agonizing history with atrocities and trauma on all sides is reduced to a story of good and bad, in which, of course, one side is always right and good and the other is always wrong—in other words, evil. A belief in religious destiny allows Hamas to justify the slaughter of innocent civilians in the name of rectifying a gross injustice, while the biblical notion of a chosen people in a world that might once again, without prior warning, decide to annihilate Jews allows the Israeli government to kill over 40,000 Palestinians and decimate Gaza in the name of self-defense. Both groups lay claim to “holy ground,” to destiny, to prophecy. Instead of asking who is right and who is wrong, the more accurate question would be how to remove religion from the discourse altogether—and return to the legal precision and clarity of the Geneva Convention; to human rights accords, bilateral treaties, and international law.

The tunnels of Gaza are deeply unsettling in ways that go beyond military strategy; they tap into something subconscious, some gut fear of the underworld. It’s not just about death, but about subversion, about the darker forces motivating human behavior. Moles live underground; ants and worms live underground. We bury the dead in the ground, but we also bury the past: we fear the reemergence of truths we prefer not to remember or know.

As an American who came to Berlin when Germany’s memory culture was in its nascent phase and who witnessed the fall of the Berlin Wall and German Reunification, I’ve long viewed the reunited halves of the formerly divided country as two parts of a single schizoid self. Because the two Germanys defined themselves in opposition to one another, because each of them claimed a moral superiority over the other, one that was contingent on the depravity of the other—that blamed the fascist past on the other—anything that questioned this dichotomy was a threat. Later, Naomi Klein’s use of the German term doppelganger to describe the mirroring effect between Israel and Palestine led me to view the relationship between Germany and Israel as between two sets of twinned doppelgangers—whereby everything that cannot be integrated into the self, particularly the stain of its own shame, is projected onto the Other, the shadow self. This liminal parallel between the two countries cements a bond that goes beyond atonement for historic guilt; it might explain why Germany has not, in fact, learned what the Holocaust should have taught us all—to see, name, and prevent the persecution and killing of oppressed peoples everywhere; why Israel is not willing to face what should be self-evident—that it is defending, through unspeakable violence, its own sacred status as victim.

~

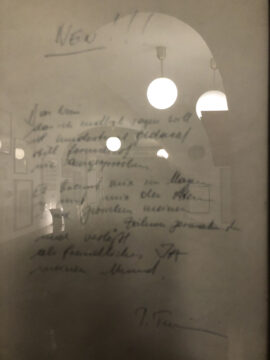

Shortly after the war in Gaza began, I left Graz for the first time to travel to the other side of the mountains visible in the distance from atop the Schlossberg. A friend had invited me on a day trip to Stainz, to a café known for its excellent pastries and art collection. The walls were densely hung with drawings, watercolors, photographs, and small works on canvas; my attention was drawn to a framed poem scribbled in pencil. It was about a “no” that the author “wants to finally say” after having “mulled it over a hundred times / silently formulated it / never said it.” No: a word of protest, of dissent, that seemed to speak directly to my own stunned silence. I had been sitting in front of the computer for days, reading survivors’ testimonies and poring through the horrific images from the music festival and kibbutz towns near the border to Gaza. The unimaginable atrocities that had been committed; the unimaginable atrocities that would inevitably follow. What can dissent mean in the face of an impending catastrophe of this magnitude? And what was the nature of this “no” that raged in the author’s stomach, that made him catch his breath, that he “crush[ed] between [his] teeth” and that came out of his mouth “as a friendly yes”? It was a brief and terrible interstice: the government’s inflammatory rhetoric made it clear that retaliation would be swift, relentless, and brutal.

Later that afternoon, back at home, I realized that the photo I’d taken of the framed note was too blurry to transcribe the poem. The camera hadn’t focused on the words, but on my own reflection in the glass. I’d hoped to identify the author, but was thrown back on myself: evidently, the problem was me and my own suppressed “no.” I tried again. Half-remembering, half-guessing, I was able to decipher a few isolated words and finally found what I was looking for: the author of the poem was the playwright Peter Turrini. The Internet spat out the usual SEO-optimized websites that promptly reduced Turrini’s existential protest to a problem of self-care: from the Catholic Church to coaching and wellness services, everyone seemed happy to offer their own over-simplified interpretation. You really don’t have to be there for others all the time, they concurred: you have to learn to say no and stop overextending yourself.

But what did Turrini mean with this “no” that had burned through his insides and transformed so agonizingly into a forced “yes”? Included in the collection A Few Steps Back, it was one of a series of poems he’d written as a form of therapy during a stay in a psychiatric clinic. It would seem that Turrini’s “no” arose out of an inner conflict, the psychological fallout of a public figure forced to take a stand and to screen what he said for potential misunderstandings and obvious no-nos. In this context, his expression of dissent and his anxiety in voicing it turn out to be a morally critical statement. In extreme times, times of violence and revenge and more violence, we are forced to take sides against our will and our own better judgment. When emotions run high, a more nuanced view is perceived as an outrage.

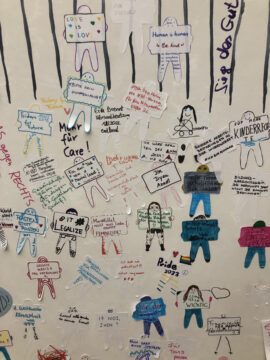

At around this time, I visited an exhibition titled “Protest!” at the Graz Museum, the back room of which had been converted into a “protest workshop.” Spread out on a large table were paper, cardboard, colored pencils, felt-tip pens, and glue, as well as “an analogue demo route planner”: a shrink-wrapped map of Graz pointing to a long tradition of street protest predating WhatsApp and Google Maps. Various questions were scrawled across two whiteboards: “Is there a cure for war?” and “What would democracy be without protest?,” left over, it seemed, from a visiting class of schoolchildren. This was my second time in the exhibition: I wanted to believe in the power of protest, that the world could still change for the better. On the table was a box of little gray men; visitors were invited to make their own tiny signs and glue them to the plastic figurines: “Protect endangered species!”; “Equal rights for everyone!”; and “Stop microplastics!” I sat down, stared at the table, and wished that I had my own army of little gray men—the sight of the empty room saddened me.

Graz looks back on a long history of local and international protest movements: demonstrations against nuclear power plants and the Vietnam War; hunger strikes against housing shortages and bad food in prison; demonstrations for women’s rights, climate protection, and an environmentally friendly transportation policy; protests against the mass-production of meat, right-wing extremism, and compulsory vaccination. Some of these movements have been successful, others remain works in progress or have become obsolete. In the exhibition, the protests that manifested as artworks were the most effective: the poems of the Black Lives Matter movement, for instance, or a series of posters by the Ukrainian group Grafprom designed around text excerpts by the poet Serhiy Zhadan, such as: “Freedom is [. . .] an abstract idea until you are personally threatened by the possibility of losing it.” The work that hit closest to home, however, was the “Rosa Luxemburg and Emma Goldman Appropriated” speech by Reni Hofmüller and Anita Hofer, in which they recited into a megaphone a litany of assertions that are essentially impossible for any sane person to deny: “We assume that every form of rule is based on violence,” and “We assume that humanity is a mass of cowards who cheer for anyone who tells them what they want to hear.” What price does one have to pay to be brave, I wondered; and what would Rosa Luxemburg and Emma Goldman have to say to us today?

Occupying the back wall of the protest workshop was a fifteen-foot-long timeline, where visitors were invited to insert the names of protest movements next to the years they took place. The year 2023 had the most entries: “Fridays for Future”; “Prevent Rent Gouging”; and “Just Smile.” It was November, and I was searching in vain for a word of protest against a war in which more than 15,000 people had already died and thousands more lay under the rubble. I paused, thought of the small army of little gray men, and asked myself if rebellion was something that could be taught or if it had to emerge from within an individual conscience. The room felt eerily empty; the young revolutionaries the workshop had been set up for were all at school. I took a piece of paper from the table, wrote “Save Palestinian Lives” on it, and pinned it to the wall of the empty exhibition space, above the year 2023. As a protest against pointless death, and in the hopes of reaching some young visitor.

~

Early in my stay in Graz, coming out of a public swimming pool one afternoon, I decided to take a different route home than usual. When I got to Griesplatz, I noticed a string of letters on the ground stenciled directly onto the pavement and so similar in color to the asphalt that reading them meant trying to find an angle for the light to reflect across their smooth surface. I followed a sentence from the final period backwards; having happened upon the end of the text and unable to read the words in their proper sequence, I could only take in fragments: “vermin and rabble,” “slapped me around,” “raging flames.” It was already clear to me that it had to be an art project; only gradually did I understand that it was also a memorial commemorating the November pogroms.

A week later, as I tried to track down artist Catrin Bolt’s work Lauftext from its starting point at Radetzkystrasse 8, former home of Chief Rabbi David Herzog, I discovered that the extensive construction underway made this impossible. Farther down the street, I was able to pick up the text midway: the string of words, interrupted by gaps in the asphalt that had been dug open and paved over again multiple times, led me several blocks in the direction of the river. Starting with the fragment “the nasal bone was seriously injured,” I realized that I was retracing, in Herzog’s own words, the path of suffering the seventy-year-old was pushed and shoved along while the old Graz synagogue went up in flames on the other side of the Mur. Herzog’s horrific report took me to the corner of Pestalozzistrasse and continued after the intersection; then, shortly after Friedrichgasse, I read that “a pyre had been set up” for him at the burning temple, “but the police were on guard at Rosenkranzgasse and they wouldn’t let anyone through.” And then, interrupted by two intersections before the bridge: “It was only due to this chance circumstance that the people present at the scene were not performing a dance [. . .] around my charred corpse.” Inaugurated in 2013 and reopened in 2021, the work—whose German title has the dual meaning of “running text” and “a text to be walked along”—carries all the way to Griesplatz: to read Herzog’s words is to follow, in his footsteps, the very path the rabbi was forced to take that cold night of November 9, 1938, when he was dragged from his home, chased through the streets, and nearly burned alive by a murderous mob as the terrible fires of Kristallnacht lit up the nighttime sky. An intervention in urban space as opposed to a conventional memorial, it catches people unawares in their everyday lives and lets the streets tell their own harrowing story. The effect—the here and now of a violent horde and of mass delusion—is all the more immediate and haunting, but also subtler, longer-lasting.

~

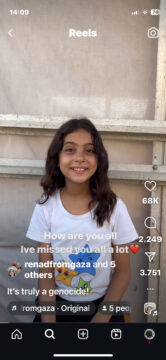

Renad Attallah, a ten-year-old Palestinian girl, has an Instagram account with nearly 700,000 followers. She films herself preparing dishes from traditional recipes, including banana rolls and nut bars; molokheya and bamya, a soup made from jute leaves and a delicious-looking dish of okra and lamb; mahshi and warag or stuffed vegetables and grape leaves; and fattah, which consists of fresh, toasted, grilled, or fried flatbread with rice and meat. Renad sets up her bowls and utensils on the dusty rubble under the shelter of a plastic tent; in an attempt to raise enough money to evacuate herself, her widowed mother, and the rest of her family out of Gaza, she graciously takes her viewers through the steps of preparing each dish from the limited ingredients available. On the days she’s too scared to venture out, she asks her viewers to pray for her and for Gaza. With her sparkling eyes and charming smile, Renad has reported on explosions, on civilian deaths, on shelling and destruction and bloodshed. After a rocket leveled the house next door in mid-August of 2024, she and her family and surviving neighbors were ordered to evacuate the eastern part of Deir al-Balah. She posts a video apologizing that she can’t make her videos anymore, that Israeli soldiers have entered the area from the east and will soon enter from the west, and that it’s far too dangerous to go outside. She is afflicted with a skin disease, and there is no medicine available to treat it. If they receive evacuation orders again, Renad says, there is literally nowhere else for them to go. “Something I haven’t figured out. If there is another displacement, where do we go, exactly? They’re everywhere except this area, and now it seems they’re coming here too.”

It’s the details of a person’s day-to-day life that allow us to identify with them more personally; details that restore a nameless victim’s individuality and humanity. Eighty years ago, in a forensic report submitted to the British occupying forces excavating Liebenau Camp, “Body No. 43” was described as having a tattoo on his chest: a bird with its wings spread, probably a swallow, “darting downwards.” The autopsy also stated that the victim was a dark-haired man of 20 to 25 years of age who had cavities in two teeth and two handkerchiefs in his trouser pocket, with a wristwatch wrapped in one of them. I would have liked to know the young man’s name and the color of his eyes; would have liked to know his birthday, and whether or not he had a sweetheart, or children or siblings; would have liked to know the meaning the swallow in flight held for him; would have liked to know the time his watch stopped ticking.