by Ed Simon

Doctor Faustus by Christopher Marlowe

Though there are stories about people trading their souls with the devil in exchange for power and knowledge before, it was the English playwright Christopher Marlowe’s 1592 play that firmly entrenched that variety of character in the literary imagination. Incidentally there was a real Johann Faust in the sixteenth century, a German wizard of whom little certain is known, but the similarly dissolute figure of Marlowe was who granted that mysterious figure a variety of immortality. Drawing inspiration from anonymous pamphlets about Faust, Marlowe crafted one of the most chilling tales about how the insatiable thirst for power can lead to damnation when we’re willing to trade our very soul. Notorious at the time, both for the author’s reputation for heresy and sodomy as well as for claims that the script itself was capable of conjuring demons, it was said that Satan himself was in attendance at the premier to evaluate how accurately he’d been depicted. “Hell hath no limits, nor is circumscrib’d,” said the play’s infamous demon Mephistopheles, “where we are is hell,/And where hell is, there must we ever be.” A despairing vision born in Marlowe’s own life, the second most celebrated Elizabethan playwright after Shakespeare who was rightly valorized for the genius of his “mighty line,” ultimately stabbed to death in a tavern fight at the age of 29.

Faust by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

Marlowe may have been the one to make the diabolical contract a mainstay of European literature, but it was the nineteenth century German poet and polymath Johann Goethe who elevated the story into the canon of eternal works. A genius who dabbled in everything from botany to anatomy, Goethe is nonetheless most celebrated for his brilliant writings responsible for the inauguration of the passionate and emotional literary movement of Romanticism. His Faust, written in two voluminous parts respectively published in 1790 and 1808, was intended to be a “closet drama,” a type of verse play meant to be read rather than performed. Drawing from the same wellspring of German myth as Marlowe, Goethe nonetheless reinvents the details and purpose of the Faust legend. Fleshing out a love interest for the wizard, Goethe also more importantly reorients the focus of the devilish contract into a wildly expansive philosophical vision, having Faust sell his soul not for power or even knowledge, but rather a very Romantic zeal for unadulterated human experience. Most arrestingly, the Faust of Goethe’s poem finds a salvation denied the magician in Marlowe’s play, though the questions raised about human freedom and depravity along the way remain disturbing, this sense that “Man errs as long as he strives.”

“Young Goodman Brown” in Mosses from an Old Manse by Nathaniel Hawthorne

Most known for that mainstay of American high school English curriculums, his novel The Scarlet Letter, Nathaniel Hawthorne was nonetheless one of the great masters of the short story. In brief, piercing provocations, Hawthorne was capable of interrogating the degradations of the soul with probing psychological acuity. Arguably his greatest short story is the disturbing “Young Goodman Brown,” the greatest work to exemplify the guilt, paranoia, and hatred in the Puritan mind, a disposition which would have such an enduring influence on the American character. Hawthorne follows his titular character, a recently married seventeenth century Puritan of that haunted hamlet of Salem, as he takes a nocturnal perambulation through the howling wilderness where he finally encounters the respectable leaders of his community engaged in an orgiastic Black Mass in which the Devil is summoned. Brown, along with his new wife, are encouraged to enter their names into Satan’s book, to sell their soul to the Lord of Evil, though the young Puritan refuses. It’s ambiguous as to whether or not Goodman’s vision is a hallucinatory walking dream or a reality, but regardless it forever impacts the man who is unable to see the supposedly pious ministers and representatives of Salem as anything other than abject hypocrites destined for damnation. The hoofprints of Hawthorne’s Devil make a pathway through American culture, from Stephen Vincent Benet’s iconic 1936 short story “The Devil and Daniel Webster” to Robert Eggers’ 2015 movie The Witch. “Evil is the nature of mankind,” says the Devil, “Evil must be your own happiness.” Where Hawthorne chills is in the possibility that such a wicked axiom might have a kernel of truth in it.

Doctor Faustus by Thomas Mann

The greatest German novel of the twentieth century wasn’t written in an Alpine half-timbered house or in a fashionable Berlin apartment, but rather in the unlikely southern California town of the sunny Pacific Palisades. That’s where Thomas Mann, Nobel Prize winner and refugee from Hitler’s Germany, used the contours of his nation’s most significant literary story to explain how that same nation had fallen for the Satanic allures of Nazism. Published in 1947, Mann’s Doctor Faustus sets its Devil’s contract in twentieth century Germany, replacing the Renaissance wizard with the brilliant avant-garde classical composer Adrian Leverkühn. Narrated by Leverkühn’s childhood friend the professor Serenus Zeitblom, Doctor Faustus nominally tells the story about the former imagining selling his soul to a devilish figure in exchange for his genius at composing, but at its core the novel takes as its task the question of how a nation which produced Beethoven and Goethe could also establish Auschwitz and Dachau. “It seems to me… that despite the logical, moral rigor music may be appear to display,” writes Mann, it “belongs to a world of spirits.” Doctor Faustus takes this observation about the irrational, chthonic, even demonic abilities of art in general, especially when applied to politics, to its logical conclusion. If the borderline-magical ability of theater, literature, and music can entrance and hypnotize us in our lives, it becomes all the more dangerous and infernal when it’s enlisted in the aims of politicians for whom the theater of the rally and the art of propaganda can convince people to commit atrocities.

Rosemary’s Baby by Ira Levin

What Ira Levin’s consummate paperback novel, fit for the beach or the airport, might lack in the gravitas of a Goethe or Mann, it makes up for in its page turning evocation of the levels which humans are willing to stoop in pursuit of that very American obsession with fame. Inextricably bound to the film adaptation of Roman Polanski produced a year after the novel’s 1967 publication, Rosemary’s Baby tells the story of an upwardly mobile artistic couple living on the Upper West Side when it was still possible to rent in that part of New York without diabolical intercession. Guy Woodhouse is a struggling actor whose talents don’t match his ambitions, which means that he’s perfectly willing to be enlisted in the infernal cause of a Satanic coven who gather in their apartment building if it means that his career prospects will thrive. What Guy has traded is Rosemary’s womb. His wife suspects that something is amiss with her unborn child, haunted by nightmarish memories of being raped by the Devil and finding claw marks on her body, but throughout the course of her pregnancy, both Guy, her neighbors, and even her gynecologist gas light her into thinking that everything is in her head. Growing fearful that her baby is intended as a Satanic sacrifice, she ultimately discovers an even more horrifying truth. “I mean, suppose you’d had a baby and lost it; wouldn’t it be the same?” Guy says to Rosemary, “And we’re getting so much in return.” Rosemary’s Baby distills the essence of a particularly self-serving cynicism in the icy dialogue of Guy who prove himself to be of far more common type of person than we might wish, humans proving just as cruel as the devil.

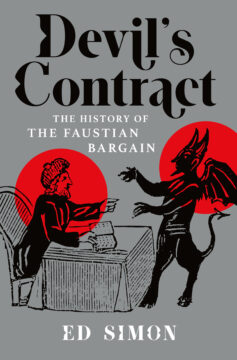

Ed Simon is the editor of Belt Magazine, an emeritus staff-writer for The Millions, a columnist at 3 Quarks Daily, and Public Humanities Special Faculty in the English Department of Carnegie Mellon University. The author of over a dozen books, his upcoming title Relic will be released by Bloomsbury Academic in January as part of their Object Lessons series, while Devil’s Contract: The History of the Faustian Bargain will be released by Melville House in July of 2024.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.