A conversation between Philip Graham and Michele Morano:

Michele Morano: Philip Graham has long been one of my favorite writers to read and to teach because of his insights, humor, and ability to challenge what we think we see. A versatile author of fiction and nonfiction— whose work has appeared in The New Yorker, Paris Review, Washington Post Magazine, McSweeney’s and elsewhere—Graham chooses subjects that explore the rippling surfaces and deep currents of domesticity at home and abroad. Each of his books illustrates Graham’s powers of perception, interpretation, and experimentation, along with his irrepressible interest in people, the more varied and unlike himself, the better. And each has contributed to the perspective of his latest project.

Michele Morano: Philip Graham has long been one of my favorite writers to read and to teach because of his insights, humor, and ability to challenge what we think we see. A versatile author of fiction and nonfiction— whose work has appeared in The New Yorker, Paris Review, Washington Post Magazine, McSweeney’s and elsewhere—Graham chooses subjects that explore the rippling surfaces and deep currents of domesticity at home and abroad. Each of his books illustrates Graham’s powers of perception, interpretation, and experimentation, along with his irrepressible interest in people, the more varied and unlike himself, the better. And each has contributed to the perspective of his latest project.

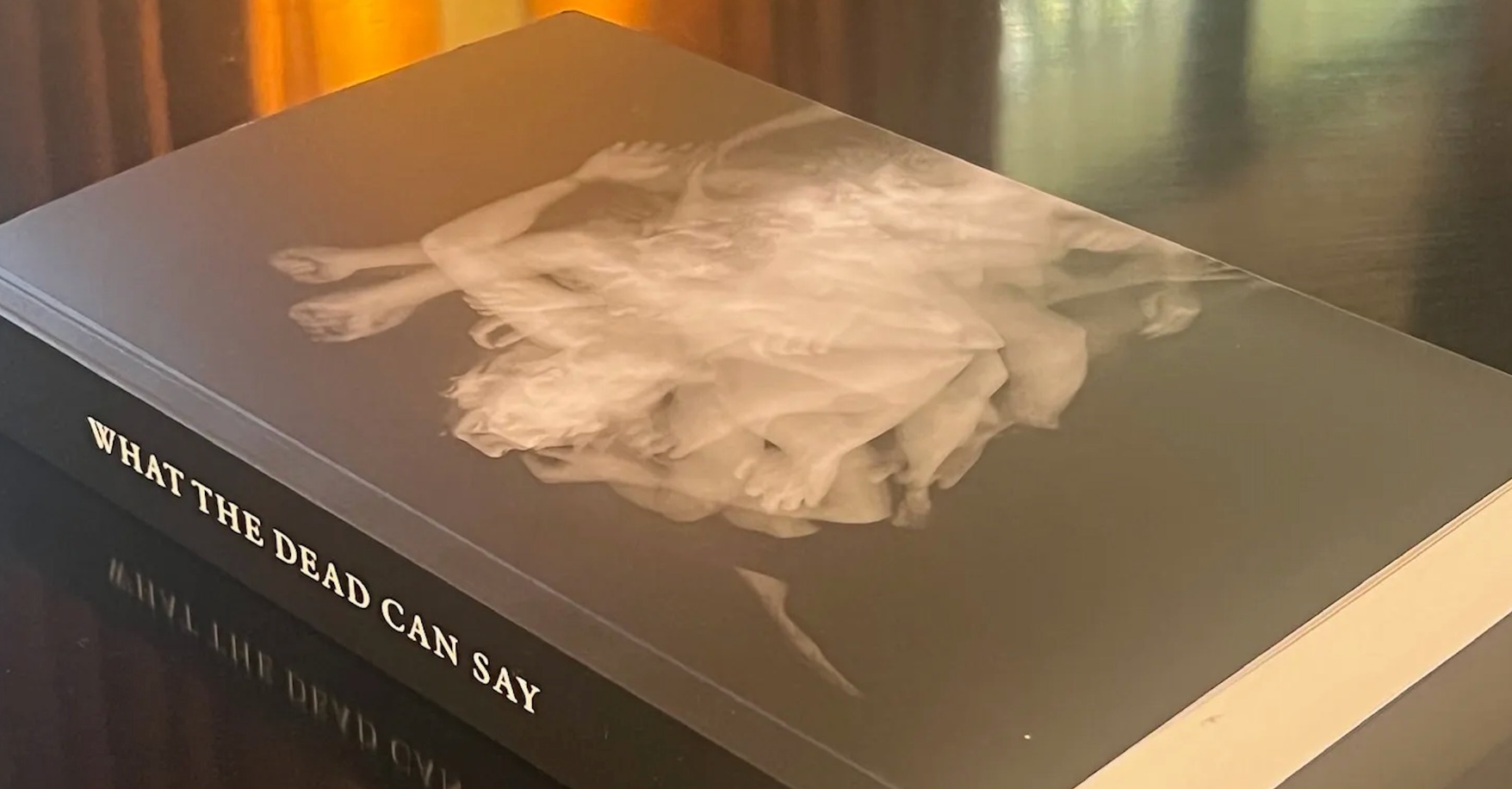

Graham’s eighth book, the novel What the Dead Can Say, is being released in serialized form in fall 2024, or perhaps it’s more accurate to say that it’s continuing to be released, in a process that began in June of 2023. If that seems mysterious, imagine happening upon a FREE copy of this book, distributed in a unique way over the last year. It’s beautifully designed, printed on quality paper, and boasts an enticing cover with no author’s name, content summary, or origin story. A straight-up ghost tale, this delightful novel takes readers on a journey through life as we know it with an otherworldly narrator who, right here in our midst, cannot help but collect other ghosts’ stories as she moves through the mortal world. It’s a beautiful, fascinating—dare I say haunting?— book for which Graham chose not to follow the traditional publishing path, though his seven previous books have been published by Scribner, Random House, William Morrow, Warner Books and the University of Chicago Press.

In a recent conversation conducted via email, I asked Graham about this choice, along with many others that resulted in the production and dissemination of a terrific, uniquely curated, work of literature.

MM: Philip, would you begin by tracing for us how you came to write a ghost story? What was the inspiration for this book, and what sorts of challenges (interior or exterior) did you encounter while writing it?

Philip Graham: First, thank you, Michele, for all those kind words. I’m a great admirer of your own work, and I’m really looking forward to our conversation.

The inspiration behind What the Dead Can Say goes back thirty years, to the summer of 1993, when I gave my father a funeral in absentia in a small West African village.

My wife Alma Gottlieb is an anthropologist, and since 1979, across a period of fourteen years, we lived for extended periods off and on with the Beng people of Côte d’Ivoire. In the summer of 1993, late word arrived from the U.S. that my father had died; I realized I wouldn’t be able to return home in time for the funeral. What to do? My father had heard so many stories from me about the Beng people, it didn’t take a great leap of imagination for me to ask the village elders if he could be given a funeral according to their customs.

The funeral was filled with rituals, a couple of animal sacrifices—a chicken and a sheep—and a village gathering for an evening of songs, prayers, food and drink. Kokora Kouassi, a religious leader in the village and an old friend, presided. In one of his prayers he said to my father’s spirit:

Rest calmly, the earth

Will be soft for you.

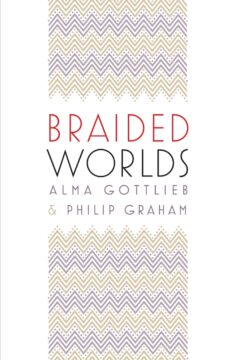

MM: Yes, you and Alma co-wrote two beautiful books about your time among the Beng, Parallel Worlds and Braided Worlds. In the latter you describe how grief after your father’s death intersected with Beng beliefs, and the impact their death rites had on your sense of the afterlife.

MM: Yes, you and Alma co-wrote two beautiful books about your time among the Beng, Parallel Worlds and Braided Worlds. In the latter you describe how grief after your father’s death intersected with Beng beliefs, and the impact their death rites had on your sense of the afterlife.

PG: To our surprise, days after the funeral, Kouassi told us that my father had appeared to him in a dream, bearing messages for us from Wurugbé, the Beng afterlife. Having been given a Beng funeral, my father was now considered a member of their afterlife, one in which the dead live social lives invisibly among the living. In the following days, Kouassi told us two more dreams with my father’s messages, and at one point he said something quite beautiful about my dad’s new existence in the spirit world: “Wurugbé is for white and black people—in Wurugbé, people are the same. They all live together.”

Through these dreams, Kouassi tried to reassure me that my dad, though seemingly far away, was actually close by. The empathy of my friend’s words inspired me, and soon ten characters arrived unbidden in my imagination, inspiring me to write short sketches of them in my notebook. I felt certain they would populate some future novel. They were all ghosts and, though located in the US, the afterlife they inhabited was similar to the Beng’s, with the dead living invisibly among the living.

Ever since then, I worked on the novel that eventually became What the Dead Can Say, while publishing four other books of fiction and nonfiction. Over those years it was my one consistent writing project, its various starts, stops, and breakthroughs sometimes in the foreground, sometimes in the background.

MM: That’s a fascinating start to a book. I’m reminded of the scene in Parallel Worlds when you first arrived in the Beng community. You set up a writing table outside the front door of your home but found it impossible to work because villagers kept stopping by to chat. That only changed when you explained what you were doing to Kokora Kouassi, and he understood writing to mean communicating with spirits.

To what extent was that true with this novel? As you created the protagonist Jenny, a ghost with the gift of absorbing all the memories (ie. stories) of other ghosts she comes into contact with, did you feel like you were tapping into an unseen world around you? I guess another way to ask this question is: what kept you coming back to this novel over a long period and across other projects?

To what extent was that true with this novel? As you created the protagonist Jenny, a ghost with the gift of absorbing all the memories (ie. stories) of other ghosts she comes into contact with, did you feel like you were tapping into an unseen world around you? I guess another way to ask this question is: what kept you coming back to this novel over a long period and across other projects?

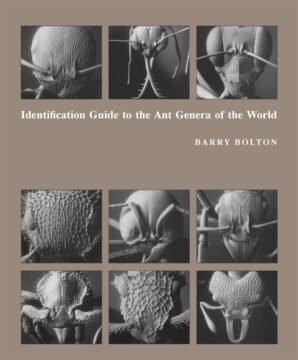

PG: Those ten characters simply wouldn’t let me go. During that summer when they first came to me, I was revising my first novel, How to Read an Unwritten Language (which was published two years later, in 1995), and yet I couldn’t help adding details in my notebook about the lives of these new ghostly characters. Which at first were largely mysterious to me! For instance, Jake, the ghost who was once a car mechanic and who develops a love of books in the afterlife by listening in on the audiobooks played by passing cars. I know a good deal about books, but nothing about cars, so researching his profession went hand-in-hand with exploring his psychology. And then there’s Tama, a myrmecologist who decides to continue her research in the afterlife by settling into an ant nest. So many books about ants to consult, including Barry Bolton’s collection of close-up, electron microscope portraits of ant faces.

MM: Tama’s story made a huge impression on me. The level of detail is extraordinary, and the amount of information offered through first-person observations changed the way I think about ants. And yes, I was going to ask about research because the characters are so fully drawn, with detailed contexts.

MM: Tama’s story made a huge impression on me. The level of detail is extraordinary, and the amount of information offered through first-person observations changed the way I think about ants. And yes, I was going to ask about research because the characters are so fully drawn, with detailed contexts.

PG: The real challenge was Jenny, whose chapters alternate with the chapters of the nine other individual ghosts. She’s the spine of the book. Jenny dies at the age of three, and denied her own life to live, she develops, over the course of the novel, the ability to absorb the memories of other ghosts. Jenny becomes the most complex of the novel’s ten characters, and the writing of her, the learning of her, took a long time.

Finally, I realized that Jenny wasn’t only a character in the novel, she was its narrator as well. She’s a storyteller. All the stories of the other ghosts are stories that she is telling; she’s offering versions of their lives as she understands them. She has picked through their memories and created narratives of their lives. So the novel begins with her telling a story, and then another, before she begins to recount her own life and afterlife.

MM: In terms of Jenny as narrator, can you tell us about creating a narrative arc with all those stories? How and when did you know where they were headed? That last question also points toward the afterlife of the novel, which is fascinating.

PG: Jenny is telling the story of her growing up. She died at the age of three, so she had a lot of “living” left to do in the afterlife. That’s one reason she’s able to absorb the memories of the ghosts she encounters. These ghosts become inadvertent mentors, each one opening a window into a new phase of Jenny’s afterlife.

And to whom is she telling these stories? Another ghost, who threatens her with an unusual sort of confinement. So Jenny has become an unwilling Scheherazade, telling stories while biding her time, planning her possible escape. And the reader is eavesdropping on this drama, as well as the individual dramas of the stories she’s telling.

MM: That tension unfolds across the novel, as we learn about that other ghost while taking in the various stories Jenny has collected. It’s like you’re spinning plates, each one fascinating, and then the reader realizes that you, too, are turning around, entering into a spin. It’s a marvelous structure.

Once the novel was completed, how did you decide on an alternative way of releasing it?

PG: The book’s structure was set very early, and by 2001 I had a full manuscript in place. Yet its emotional core was still developing. Over the years I gave public readings from it, published seven of the chapters as free-standing stories, and many friends read the manuscript and gave me invaluable advice. When I finished what I considered the final version in March of 2022, I felt it had been more than sufficiently vetted, editorially. I also knew that I had little stomach for entering once again into the maw of traditional publishing, with all its inevitable compromises. Not with this book! It meant too much to me. In recent years the corporatization and commercialization of publishing has accelerated alarmingly, as numerous articles have observed, with hair-raising titles like “Is the Publishing Industry Broken?” “But What About the Books?” “Book Publishing’s Broken Blurb System,” and “How Has Big Publishing Changed American Fiction?”

Think of the hurdles a writer has to go through in the current system, in order to reach a reader: agent, editor, marketing staff, overworked in-house publicist, then the slim chance of enough positive book reviews (if any reviews at all) to land copies of one’s novel or memoir on a bookstore’s shelves, the spine facing out for maybe three months before being shipped back. Unless, of course, you’re a TV star and you’ve written a cookbook.

I began to consider attempting something completely different, inspired by the example of independent filmmakers who take creative control, believing enough in their artistic vision to assume the financial risk and letting the chips fall where they may.

First I hooked up with a very cool design team: Amie Cooper of the Actualizers (a company that manages book production), who then brought Amy Fortunato, a superb book designer, to the project. We honed my vision of a novel that would intentionally reject most of the norms of commercial book presentation. There are no (lying or exaggerated) blurbs on the back cover, no (puffed-up) bio of the author on the back flap, and no (give-too-much-away) description of the book on the inner flap. No title or author’s name on the cover, and a cover image of my choice. No author’s name on the title page, except for the pseudonym “Author Unseen.” Not a single sales pitch to be found. And not a single editor or a marketing staff to say No to anything I came up with. A writer with agency, what a concept!

First I hooked up with a very cool design team: Amie Cooper of the Actualizers (a company that manages book production), who then brought Amy Fortunato, a superb book designer, to the project. We honed my vision of a novel that would intentionally reject most of the norms of commercial book presentation. There are no (lying or exaggerated) blurbs on the back cover, no (puffed-up) bio of the author on the back flap, and no (give-too-much-away) description of the book on the inner flap. No title or author’s name on the cover, and a cover image of my choice. No author’s name on the title page, except for the pseudonym “Author Unseen.” Not a single sales pitch to be found. And not a single editor or a marketing staff to say No to anything I came up with. A writer with agency, what a concept!

And this was only the beginning.

MM: There was no sales pitch because you weren’t selling hard copies, right? It’s a stunning book, an art object, really. The paper is high quality, the cover is gorgeous, the book feels weighty in the hand. Its minimalist design seems to make way for the stories to move freely. Receiving the printed copies must have been such a different experience from receiving the first shipment of your novel from a traditional publisher. How many books were in that first “print run”? And what happened once you had them?

PG: No bar code, so no possible sales. Instead, I would gift them. But how to distribute this print run of 1,000 copies?

Little Free Libraries.

For a few years I had been noticing the little libraries in my neighborhood, how books would arrive and depart over the course of a few weeks. The best of these libraries seemed to have developed a healthy exchange of books among avid readers. It turns out that there are now 150,000 Little Free Libraries scattered across the country, and the Little Free Library organization has an app that lets you locate every one of them on a map. Each registered library receives its own dedicated pop-up page, usually accompanied by a photo of the library, and a statement by the library’s steward about what sort of books are preferred. Alma and I spent a good deal of time scrolling through that app, identifying any Little Free Library aiming at readers that might most welcome the presence of my novel. Slowly we curated what became a five-month trip that would take us through 28 states, up and down the East Coast, then across the country from Rhode Island to New Mexico, then up and down the Mountain states and then up the West Coast, from Los Angeles to Seattle, depositing the vast majority of the print run in those little libraries we’d identified.

For a few years I had been noticing the little libraries in my neighborhood, how books would arrive and depart over the course of a few weeks. The best of these libraries seemed to have developed a healthy exchange of books among avid readers. It turns out that there are now 150,000 Little Free Libraries scattered across the country, and the Little Free Library organization has an app that lets you locate every one of them on a map. Each registered library receives its own dedicated pop-up page, usually accompanied by a photo of the library, and a statement by the library’s steward about what sort of books are preferred. Alma and I spent a good deal of time scrolling through that app, identifying any Little Free Library aiming at readers that might most welcome the presence of my novel. Slowly we curated what became a five-month trip that would take us through 28 states, up and down the East Coast, then across the country from Rhode Island to New Mexico, then up and down the Mountain states and then up the West Coast, from Los Angeles to Seattle, depositing the vast majority of the print run in those little libraries we’d identified.

MM: Several of those libraries are located in Chicago, not far from my home, and I had the pleasure of driving you and Alma around to them one morning in September. That was an enlightening experience, first because it introduced me to just how many registered Little Free Libraries there are and then because of the assessments about where your novel would keep good company. We rejected quite a few because the curation seemed unlikely to draw the reader you’d written for. This is every author’s dream, right? To hand-select the situation in which the book finds an audience, except that some of us might be uncomfortable with the serendipity involved, not to mention the five-month road trip!

PG: The whole endeavor was much easier imagining than planning and accomplishing. There were times, such as driving around northern Indianapolis and finding not a single little library that hosted decent books, or traveling on an isolated stretch of road linking northern Colorado with southern Wyoming, or the hours of numbering the 1,000 copies of my novel in black ink and then signing each copy with invisible ink, that I sometimes regretted ever coming up with this wild idea. But most often, Alma and I reveled in our 10,000 miles of experience. And driving around Chicago with you was a particular treat, since you quickly embraced the thrill of the hunt.

MM: Your book distribution is just the beginning of this novel’s release, but before we get to what comes next, what were some of the highlights or just wild experiences of that trip?

PG: First, our country is so physically varied and beautiful, and we have become just as diverse culturally. We did some shopping in an African grocery store in Wichita, Kansas. In a Columbus, Ohio suburb we saw a long line of women in chadors waiting outside to buy ice cream cones. Interracial couples everywhere. Pride flags and Black Lives Matter and No Hate posters everywhere, in Red as well as Blue states. And what a surprise, to drive through enormous wind turbine farms in Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas.

PG: First, our country is so physically varied and beautiful, and we have become just as diverse culturally. We did some shopping in an African grocery store in Wichita, Kansas. In a Columbus, Ohio suburb we saw a long line of women in chadors waiting outside to buy ice cream cones. Interracial couples everywhere. Pride flags and Black Lives Matter and No Hate posters everywhere, in Red as well as Blue states. And what a surprise, to drive through enormous wind turbine farms in Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas.

But above all, the Little Free Libraries offered their own surprises. A little library in Amarillo, Texas that offered the complete works of Oscar Wilde. In Madison, Wisconsin, a LFL that offered books on one shelf and food for the homeless on another. In Baltimore, a library that offered seeds for hopeful gardeners. South Philadelphia is dotted with tiny parks, and each of them hosts a Little Free Library (and every one we came upon contained a lively selection of books). In Lewisburg, Pennsylvania, a LFL in a butterfly park. A LFL painted in Pride flag colors on a dirt road outside of Cheyenne, Wyoming. A little library embedded in a towering tree in Iowa City. So many beautiful, lovingly-constructed little libraries: in the shape of a lighthouse (Portland, Maine), a library made out of the parts of a grand piano (Beacon, New York), or shaped like an apartment house (Wilmington, Delaware) or an Afghani bus or a castle (Chicago). And then there was the LFL in Eugene, Oregon, on Cheshire Lane, that was guarded by a sculpture of the Cheshire Cat, perched on the overhanging branch of a nearby tree.

But above all, the Little Free Libraries offered their own surprises. A little library in Amarillo, Texas that offered the complete works of Oscar Wilde. In Madison, Wisconsin, a LFL that offered books on one shelf and food for the homeless on another. In Baltimore, a library that offered seeds for hopeful gardeners. South Philadelphia is dotted with tiny parks, and each of them hosts a Little Free Library (and every one we came upon contained a lively selection of books). In Lewisburg, Pennsylvania, a LFL in a butterfly park. A LFL painted in Pride flag colors on a dirt road outside of Cheyenne, Wyoming. A little library embedded in a towering tree in Iowa City. So many beautiful, lovingly-constructed little libraries: in the shape of a lighthouse (Portland, Maine), a library made out of the parts of a grand piano (Beacon, New York), or shaped like an apartment house (Wilmington, Delaware) or an Afghani bus or a castle (Chicago). And then there was the LFL in Eugene, Oregon, on Cheshire Lane, that was guarded by a sculpture of the Cheshire Cat, perched on the overhanging branch of a nearby tree.

And because Alma and I had curated which LFLs we’d visit solely on the basis of the quality of the books they contained, and because a well-kept Little Free Library knows no socio-economic boundaries, we traveled to a diverse array of neighborhoods in whatever town or city we found ourselves. More than once we’d come upon a little library with a bilingual collection of books, accompanied by a pasted note on the window welcoming the newest immigrant population to the neighborhood (and what a delight, to find in one of those libraries a Spanish language edition of Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude).

And because Alma and I had curated which LFLs we’d visit solely on the basis of the quality of the books they contained, and because a well-kept Little Free Library knows no socio-economic boundaries, we traveled to a diverse array of neighborhoods in whatever town or city we found ourselves. More than once we’d come upon a little library with a bilingual collection of books, accompanied by a pasted note on the window welcoming the newest immigrant population to the neighborhood (and what a delight, to find in one of those libraries a Spanish language edition of Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude).

There are curious, serious readers everywhere. There’s something spiritual about a Little Free Library: each one is a form of public service, and a kind of Rorschach blot of a street’s or neighborhood’s taste in reading. Yet as a literary phenomenon, this network of little libraries remains largely under the radar. Throughout our travels, I felt honored to enter the invisible slipstream of fellow citizens who love and freely share books.

MM: What a fascinating perspective on the reading public, as well as on folks who love and respect books as objects. Let’s say I’m a lucky visitor to a Little Free Library where an intriguing novel, What the Dead Can Say, catches my eye. There’s no author listed, but there is a QR code inside the book, hidden behind the back flap, and when I scan it, something delightful happens. Tell us about that?

MM: What a fascinating perspective on the reading public, as well as on folks who love and respect books as objects. Let’s say I’m a lucky visitor to a Little Free Library where an intriguing novel, What the Dead Can Say, catches my eye. There’s no author listed, but there is a QR code inside the book, hidden behind the back flap, and when I scan it, something delightful happens. Tell us about that?

PG: The hidden QR code was the idea of my son-in-law, Andrew Samuels. He suggested that it link to my author’s website, but I didn’t want my identity revealed so easily. Yet his idea of a QR code intrigued me. While still in the process of designing my book I eventually thought, why not link to an Instagram page, where Alma and I could download photos of the little libraries where I’d be depositing copies of my novel? Yet what a boring Instagram page that would be: hundreds of photos of Little Free Libraries, one after the other after the other . . .

Then in May of 2022, while the book’s physical design was still being fine-tuned, Alma and I were driving on a Rhode Island side road near the coast and came upon a Little Free Library that stood next to a cemetery. How could I not stop and take photos, from an angle that would include both the library and the nearby tombstones?

Over the next few days that image kept returning to me, until I realized it could be the beginning of a story, set 20 years after the events of the last page of the printed book, where Jenny—the central character of the novel—discovers the pleasures of Little Free Libraries, and that her narrative could be fueled by my own coming travels across the country. In a sense, Jenny would be hovering invisibly by my side, and together we would improvise the developing story of her journey. So, the hidden QR code became a portal to an extension of the novel and made the 10,000 mile trek around the country more interesting, because serendipity and coincidence often ruled the twists and turns of Jenny’s additional story.

MM: Again, this seems like a writer’s dream: to continue inhabiting a character after the novel has ended. What has the process of writing this after-story been like?

MM: Again, this seems like a writer’s dream: to continue inhabiting a character after the novel has ended. What has the process of writing this after-story been like?

PG: Initially I didn’t have a story arc in mind. I simply thought that, like me, Jenny would travel (though invisibly) from one little free library to another. I was open to whatever narrative might develop.

Eventually I decided that the cemetery beside that little library would be a good place to start. Jenny is hiding there from other ghosts (she asserts that no ghosts like graveyards), because she recently absorbed a ghost’s memories that were so terrible she can’t imagine passing them on. She’s hiding from the temptation of sharing memories again and intuitively understands that the solution to her dilemma lies in books, in reading. And so begins Jenny’s journey from one Little Free Library after another.

MM: So the Little Free Library tour was both an end-point for the novel and a catalyst for continued writing. Can you tell us about that, as well as about how you knew when Jenny’s story wound down?

![]() PG: Often during our travels, while depositing a book I’d also pick one up. I enjoyed so much The Examined Life: How We Lose and Find Ourselves, by the psychoanalyst Stephen Grosz, that I actually read it twice, and so Jenny of course finds and reads it too, and quotes from it in one of the early Instagram stories. She does the same with a novel by Rachel Cusk, Outline—another of my discoveries. Coming upon a little library built out of the parts of a piano inspired an extended Jenny story—it reminds Jenny of another of her ghosts, a troubled violinist who died in Budapest.

PG: Often during our travels, while depositing a book I’d also pick one up. I enjoyed so much The Examined Life: How We Lose and Find Ourselves, by the psychoanalyst Stephen Grosz, that I actually read it twice, and so Jenny of course finds and reads it too, and quotes from it in one of the early Instagram stories. She does the same with a novel by Rachel Cusk, Outline—another of my discoveries. Coming upon a little library built out of the parts of a piano inspired an extended Jenny story—it reminds Jenny of another of her ghosts, a troubled violinist who died in Budapest.

But perhaps the oddest example of Jenny’s and my parallel travels concerns the writer Pat Barker. In a little library on Cape Cod, I came upon her Booker Prize-winning novel about World War I, The Ghost Road. I’d always wanted to read this book, and so I plucked it for myself. Yet, after reading about 20 pages, I realized that this novel wasn’t stand-alone, but the last of a trilogy. Ah well, I thought, maybe I’ll come upon the other two books later in this trek. And sure enough, two weeks later, in Albany, New York, I came upon The Eye in the Door, the trilogy’s second novel. But for the months-long remainder of the trip around the country, no further luck.

Then, in Berkeley, California, only days away from completing our long Little Free Library journey (the last stop would be Seattle) I found the first book, Regeneration. I could finally begin reading Barker’s trilogy! Which I did (along with, as always, my fictional Jenny). On page 103 I came upon a scene of horror that reminds my fictional Jenny of what started her journey to begin with—a ghost’s memory that so unsettled her. This recognition leads Jenny to the end of her story. And so, as Alma and I finished up our trek, so did Jenny—a parallel development that it would have been impossible for me to plan.

MM: That’s an awesome series of events. As someone who loved the novel and has followed its Instagram page, I’m eager to read the rest of Jenny’s story. When and how will you make that available?

PG: What the Dead Can Say has its own afterlife! This fall, we’ve just launched a digital serialization of the novel. We’ll release one chapter each week, on the Ghost online platform. Yep, Ghost! The perfect alternative to Substack—which, unfortunately still allows white supremacists to monetize their rantings.

However, the digital version of What the Dead Can Say is not identical to the printed book; it offers lots of bonus content. First, a section titled “What Jenny Could Have Said (but didn’t),” is placed at the end of each chapter, and develops one or two hidden narratives in that chapter. For instance, in the What Jenny Could Have Said section following the chapter featuring Jake (“Rewind”), Jenny tells us three of his dreams that she managed to uncover, dreams he had never allowed himself to remember—to his great emotional loss.

Each chapter also features one or two spare line drawings by my daughter-in-law, the artist Emily K Mell, images that I think beautifully capture the spirit of the novel. And Amy Fortunato has created a beautiful design environment for this version of the book, as she also did with the print version and the Instagram cycle of stories.

Each chapter also features one or two spare line drawings by my daughter-in-law, the artist Emily K Mell, images that I think beautifully capture the spirit of the novel. And Amy Fortunato has created a beautiful design environment for this version of the book, as she also did with the print version and the Instagram cycle of stories.

And then there’s the Jennyverse Chorus, a section on the site where 21 authors (including you!) read brief excerpts from the novel’s 21 chapters. Which brings me to one more difference from the print edition of the novel. While the print version has 19 chapters, the digital serialization on the Ghost online platform has two bonus “final” chapters. The 20th is a revised and expanded version of the Instagram story narrative that takes place twenty years after the last page of What the Dead Can Say. The next, and truly final chapter takes place over one hundred years later, and recounts a journey that Jenny embarks on after some necessary hesitation, a journey that perhaps no other ghost has ever attempted before. I’ve always seen Jenny as an endlessly curious ghost, and I’d like to gift her in this last chapter with an afterlife deserving of her imagination and pluck.

MM: It’s worth emphasizing that in this age of authors doing ever-more of the editing and publicity for the work, you took that situation to its logical conclusion and did the distribution, too. I know you were able to do that because as a retired professor you had the time and the means (not to mention an awesome coordinator and co-pilot in your wife Alma) to embark on that road trip. But I know early-career writers who have taken themselves on cross-country book tours, driving between independent stores, and then staying with friends as you did.

PG: Bravo and brava to them! If I had known this before my own trek, I could have shared notes and tips.

I don’t see my Little Free Library journey as a template for other writers, though. As you mention, I have, at this late point in my life, the time and a lack of institutional restraint to go about my business. And I never could have accomplished this mad scheme without the extraordinary logistical and emotional support of Alma. If there’s anything to be learned from my experience, it’s that writers don’t have to be afraid to discover their own agency in the creation and the distribution of their work, at whatever point in their career.

At the same time, I can’t deny that I have had mostly positive experiences with editors, publicists and book cover designers in the various New York and university publishing houses that launched my earlier books. People who work in publishing love books. They champion authors. But they are working in a system that over the years has increasingly become ever more commercialized and creatively restraining. As for bookstores, I adore them and the brave souls who labor mightily to keep them afloat. In nearby Providence, I regularly patronize three independent bookstores, and I can’t imagine life without them. But they too work within a system that, at least for this book project, I wanted to sidestep in order for my novel to find its own peculiar way.

Perhaps I should mention here that each copy of What the Dead Can Say also contains a small printed card with the words, “Compliments of Author Unseen.” And below that appears my favorite quote by the French-Canadian writer Jacques Poulin (from his marvelous novel, Autumn Rounds): “Books were constantly moving around and traveling, and it was the best thing that could happen to them.” I like to think that every copy of my mysterious book, a gift delivered by hand to Little Free Libraries across a wide patchwork of states, has found or will eventually find a home. Right now, some copies might still sit on a little library shelf, waiting to be chosen. Other copies have been picked and taken home; they sit on a night table or balance within a stack of books beside a reading chair, waiting to be read. And perhaps some copies, having been read and enjoyed, now join a shelf of other favored books. Some might be lent to friends who are fellow readers. Every book can now live out its own little fate.

MM: I suspect that’s the case in Chicago, at least in my neighborhood, where your novel quickly disappeared from the Little Free Library I regularly walk past—and hasn’t returned! Those of us who have hard copies of the book are very lucky, and I’m delighted that everyone else now has electronic access to What the Dead Can Say. I’ll be re-reading it on Ghost and enjoying the pleasures of serialization. Thank you, Philip, for taking the time to talk about this fabulous project.

***

Michele Morano is the author of the essay collections Like Love and Grammar Lessons: Translating a Life in Spain, and of many short works published in journals and anthologies including Best American Essays. She teaches creative writing at DePaul University in Chicago.

Philip Graham is the author of eight books of fiction and nonfiction, including The Art of the Knock: Stories, The Moon, Come to Earth: Dispatches from Lisbon, and (as Author Unseen) What the Dead Can Say. His work has appeared in The New Yorker, Washington Post Magazine, Paris Review and elsewhere. A co-founder of the literary/arts journal Ninth Letter, he is currently the Editor-at-large for the journal’s website.

***

Cover image for What the Dead Can Say is by Paul Maria Schneggenburger: “The Sleep of the Beloved, no. 52”