by Steve Szilagyi

Herb Gobel opened Trophy Recording in downtown Boston in 1948. It was a state-of-the-art studio. Perfect for the artists Herb idolized. Big bands like Artie Shaw and Stan Kenton. Vocalists like Frank Sinatra and Peggy Lee. An era of composers, arrangers and sight-reading musicians. By the time I saw Trophy Recording in 1972, the place had gone to ruin. Cobwebs on the music stands. Cigarette burns and coffee stains on the control board. A flock of pigeons roosting in the ceiling. The proprietor himself didn’t look much better. Pale, bleary-eyed, tie dangling under the open collar of his dingy white shirt.

Herb looked like a man who didn’t know what hit him. But appearances deceive. Herb knew quite well what hit him. Rock ‘n’ Roll.

“It shouldn’t have happened,” he said, pulling a whisky bottle from under the control board. “It should have come and gone. Like all the other novelty fads” – meaning calypso, Hawaiian and “that Desi Arnez stuff.”

No union musicians. Rock ‘n’ Roll was a joke at first. The musical establishment put Be-Bop-a-Lu-La into the same category as Aba Dabba Honeymoon. Guys like Herb thought it would be absorbed into the musical mainstream. Rock ‘n’ roll songs would be arranged for horns, strings and accordions, and life would go on. No union musicians would lose their jobs.

But that didn’t happen. To survive, Herb had to push the music stands into the corner and learn how to record garage bands. It wasn’t hard. Suburban kids with new guitars weren’t very demanding. In time, Herb stopped seeing recording as a craft, and came to view it as a grift.

Herb had only one working microphone. The rest were dead mikes he’d make a show of carefully setting around the drums and amps. “They don’t know the difference,” he said. “If the playback is loud enough, they all go – whooo!”

When Herb was paid by the client (cash only) he stuffed the money into his pocket and disappeared into the Combat Zone for the afternoon. “I don’t know where he goes,” said his assistant, a hopeful musician who swept the floor in exchange for studio time. “I suppose someday he’ll never come back.”

“BLAAANG!” About ten years later, I met another man who owned a recording studio. Ken Lipkin was a drummer who’d played on a few John Lennon albums. He took the money from those sessions and built a studio in New York’s Garment District. Ken’s studio was made for the rock of the early seventies. Mellow. Slightly jazzy. Long solos. Ken had 16 tracks to play with. Musicians could pile instrument on top of instrument, and take weeks fiddling around with one song.

Ken had long stringy hair, a bald spot, and a little paunch. He was usually good humored. Weed helped. By the time he finished his studio, disco was finishing off the kind of rock he liked. Then came punk and New Wave. Simple songs with three chords. Ken laughed about it. “BLAAANG!” he’d grimace and make a mock strumming motion. “BLANGA-LANGA-LANGA-LANGA …”

Punk and New Wave, and electronica groups (“BLEEP-BLOOP”) came through the door. Ken set up the mikes and took their money. None of it was his cup of tea, but it was keyboards, guitars and drums, and he could relate. And the bands were still impressed with his John Lennon anecdotes.

But Ken wasn’t prepared for what came next. Rap. Ken didn’t know what to make of the first rapper who booked a session. It was just one guy, a friend, and an electronic beat box. The rapper called the beat box, “My music.” Listening to the playback, the artist asked Ken to “Bring up the music” – meaning the drum box.

Ken laughed as he recalled his early rap sessions. Like the rest of us, he’d loved Rapper’s Delight by the Sugarhill Gang. And like many of us, he thought it was a one off, novelty hit. But like rock ‘n’ roll, rap was a novelty that took over the world. Pretty soon, Ken closed up shop. Digital recording was coming down the pike, meaning Ken would have had to learn a whole new technology. He and the weed were not into it. And rappers didn’t know from John Lennon.

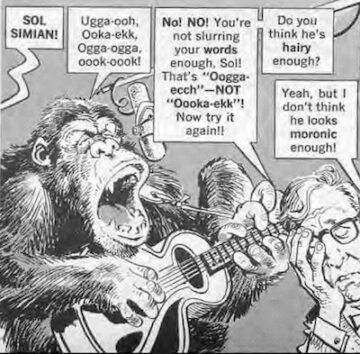

Cruder and more animalistic. Like many men my age, I have the content of every MAD magazine from the 1950s to mid-60s graven on my memory. When I think about Herb Gobel and Ken Lipkin, I remember a strip from 1964. It was called “MAD’s Teenage Idol Promoter of the Year”. The premise was that starting from the days of Sinatra and Bing Crosby, up through Elvis Presley and the Beatles, each generation of pop singers was cruder and more animalistic than the last. Finally, MAD’s promoter proudly unveils what he believes will be the ultimate pop singer: “Sol Simian”, an actual gorilla with a guitar.

In the final panel of the strip, Sol Simian can be seen howling into a microphone:

“Ugga-ooh, Ooka-ekk!”

“Do you think he’s hairy enough?” asks the promoter.

“Yeah,” says someone else, “but I don’t think he looks moronic enough.”

Glossy recordings. My contacts with the recording world faded in the 1980s and 90s, and it wasn’t until the 2020s that I again found myself in a professional studio – a rustic country house in the Midwest, where the high-ceilinged living room was now a sound-optimized performance space.

This studio was built to pamper the tastes and ears of spoiled early 1970s rock stars. The mixing board was as wide as two pool tables across. It had 64 channels, with hundreds of dials, switches and faders. There were a kitchen, bedrooms, and woods outside. Sofas lined the room, so producers and musicians could get comfortable while they got high and endlessly tweaked their glossy recordings.

The huge mixing board is a thing of beauty. But today, it goes entirely unused. The young engineers who run the studio can control 64 channels and more on a single laptop. They could easily run a complex session on an iPad or a phone.

Christopher Mintz, the latest owner, says his ideal customers these days are what he calls blues lawyers. “These are guys that had bands in high school,” he explains. “Now they’re successful professionals, and they want to go back and make that record they always dreamed of. The great thing is, they have lots of money and book whole days. I’ve got a dentist with a group coming in now …”

I stuck around to listen. The dentist’s band was really good! The difference, though, between now and the days of Herb Gobel, Ken Lipkin and their like, is that these days, nobody cares.

The end of scarcity. There are thousands of bands and musicians out there playing music that is as good if not better than anything from the heyday of the big bands, rock ‘n’ roll, country western and R&B.

Conservatories are turning out stupendous jazz players. There are bluegrass bands on every corner. And I firmly believe that every small to medium-sized city in America has at least three blues guitarists as good or better than Eric Clapton. But who has time to listen? Beginning in the late 20th century, technology took over and mainstream pop flowed into a thousand different rivulets.

Gorillas? For all I know there could be hundreds of them out there, each with his or her fans and a couple of thousand views on YouTube.

I like to imagine Sol Simian, the original singing gorilla, sitting at the end of the bar, shaking his head sadly. “The whole business has gone to hell,” he says. “The gatekeepers are powerful and corrupt, and they make sure only the few people at the top are making any money. When our generation dies, everything we thought was music will disappear with us. People will have better things to do.”

The gorilla sighs and goes over to the dusty old jukebox, bends over and plugs it in. His eyes run over the lighted song titles. “Ugga-ooh, Ooka-ekk,” he says. “Now that was a song.”

***

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.