by Azadeh Amirsadri

It’s a warm June day in 1976. I am 17 years old and standing with my family and my 30-year-old husband’s family at the airport In Tehran. My mother, grandmother, and mother-in-law have red eyes and red nose tips from crying and trying hard not to cry in public. My mother-in-law is seeing her firstborn leave again to go overseas, but this time with a new wife instead of going alone. My mother is seeing her daughter start a new life far away from her, and years later she told me a part of her was always not sure she had made the right decision to marry me off so young. In the picture we took at the airport, I am standing by my younger sisters, carrying a very cool beige Samsonite makeup case and from the look of my sisters and me, I doubt we could have known that it would be the last time we were in Iran together as a family, ever. My sisters and I are looking at the camera, I am scared, excited, and sad; my sisters are standing there, wondering probably what will happen next. When I say goodbye to my grandmother who had raised me for the first five years of my life, she discreetly puts a folded one-hundred-dollar bill in my hand and closes her fingers on it. She whispers to me that she wants me to buy something for myself when I get to my destination.

The flight that brought me to America had a stop in the UK and my husband, whom I had met three months earlier, bought himself a white wool Irish sweater at the long layover at the airport, as did the young Iranian woman who sat on the aisle seat next to me. She spoke Persian with an American accent even though she was Iranian, and had come to visit her family and was returning to the States. I disliked her right away for no good reason except that she had bought her Irish sweater and I hadn’t bought anything. I also envied the fact that she was traveling on her own. She and my husband were speaking to each other mostly in English, because it was easier for her, and she was telling him about her college in Boston, how far Philadelphia, our final destination was from the airport in New York, and other things that must have not been worth translating for me, as I didn’t speak English. With their new matching sweaters, smoking Dunhill cigarettes, and speaking to each other, I felt a complicity between them that excluded me.

We landed at JFK airport, a place my grandmother had warned us about because according to her, it was the largest airport in the world. She had asked him to hold my hand there and not let go the whole time, worried I might get lost in the size of that place. Quickly after landing, my husband bought a Popular Mechanics magazine at the newsstand and his colleague who was on the same flight, bought a Playboy magazine. As he was looking at the centerfold picture, he said to my husband, “My magazine’s pictures are better than yours,” making both of them laugh and making me extremely uncomfortable, feeling naked and exposed. The Boston girl got picked up by her boyfriend who lifted her in his arms and I disliked her even more because she could have a boyfriend who loved her and whom she loved, something I wasn’t allowed to have. Read more »

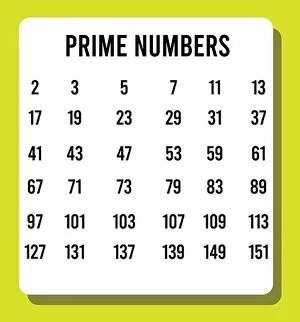

Prime numbers are the atoms of arithmetic. Just as a water molecule can be broken into two hydrogen and one oxygen atoms, 12 can be broken into two 2s and a 3. Indeed, the defining feature of a prime number is that it cannot be factored into a nontrivial product of two smaller numbers. Two primes that are easy to remember are

Prime numbers are the atoms of arithmetic. Just as a water molecule can be broken into two hydrogen and one oxygen atoms, 12 can be broken into two 2s and a 3. Indeed, the defining feature of a prime number is that it cannot be factored into a nontrivial product of two smaller numbers. Two primes that are easy to remember are

When I was growing up, my mother and I would sometimes read or recite poetry to each other. Ours was not a poetic household, and my father would occasionally complain: “If poets have something to say, why don’t they just say it?” But we thought they did say it, albeit indirectly sometimes, and we continued with our Longfellow, a bit more quietly.

When I was growing up, my mother and I would sometimes read or recite poetry to each other. Ours was not a poetic household, and my father would occasionally complain: “If poets have something to say, why don’t they just say it?” But we thought they did say it, albeit indirectly sometimes, and we continued with our Longfellow, a bit more quietly.

Renowned and respected for her scholarship, her history of authorship of many books on dictatorship and her political experience, is it any wonder that Anne Applebaum’s new book Autocracy, Inc. The Dictators Who Want to Run the World has been so critically received; she is an expert on her subject. This slim volume provides us with an incisive exposition and analysis of how autocrats function in the world today, securing their own personal power and wealth, and in Applebaum’s view, posing a threat to democracies.

Renowned and respected for her scholarship, her history of authorship of many books on dictatorship and her political experience, is it any wonder that Anne Applebaum’s new book Autocracy, Inc. The Dictators Who Want to Run the World has been so critically received; she is an expert on her subject. This slim volume provides us with an incisive exposition and analysis of how autocrats function in the world today, securing their own personal power and wealth, and in Applebaum’s view, posing a threat to democracies.

Every time I read or watch anything about the election I hear some variant of the phrase “margin of error.” My mathematically attuned ears perk up, but usually it’s just a slightly pretentious way of saying the election is very close or else that it’s not very close. Schmargin of error might be a better name for metaphorical uses of the phrase.

Every time I read or watch anything about the election I hear some variant of the phrase “margin of error.” My mathematically attuned ears perk up, but usually it’s just a slightly pretentious way of saying the election is very close or else that it’s not very close. Schmargin of error might be a better name for metaphorical uses of the phrase. Philosophical reflection on artificial intelligence (AI) has been a feature of the early days of cybernetics, with Alan Turing’s famous proposals on the notion of intelligence in the 1950s rearming old philosophical debates on the man-system or man-machine and the possibly mechanistic nature of cognition. However, AI raises questions on spheres of philosophy with the contemporary advent of connectionist artificial intelligence based on deep learning through artificial neural networks and the prodigies of generative foundation models. One of the most prominent examples is the philosophy of mind, which seeks to reflect on the benefits and limits of a computational approach to mind and consciousness. Other spheres of affected philosophies are ethics, which is confronted with original questions on agency and responsibility; political philosophy, which is obliged to think afresh about augmented action and algorithmic governance; the philosophy of language; the notion of aesthetics, which has to take an interest in artistic productions emerging from the latent spaces of AIs and where its traditional categories malfunction; and metaphysics, which has to think afresh about the supposed human exception or the question of finitude.

Philosophical reflection on artificial intelligence (AI) has been a feature of the early days of cybernetics, with Alan Turing’s famous proposals on the notion of intelligence in the 1950s rearming old philosophical debates on the man-system or man-machine and the possibly mechanistic nature of cognition. However, AI raises questions on spheres of philosophy with the contemporary advent of connectionist artificial intelligence based on deep learning through artificial neural networks and the prodigies of generative foundation models. One of the most prominent examples is the philosophy of mind, which seeks to reflect on the benefits and limits of a computational approach to mind and consciousness. Other spheres of affected philosophies are ethics, which is confronted with original questions on agency and responsibility; political philosophy, which is obliged to think afresh about augmented action and algorithmic governance; the philosophy of language; the notion of aesthetics, which has to take an interest in artistic productions emerging from the latent spaces of AIs and where its traditional categories malfunction; and metaphysics, which has to think afresh about the supposed human exception or the question of finitude.