by Rachel Robison-Greene

Public philosophy isn’t new. The image that many people conjure up when they picture a quintessential philosopher—the image of Socrates—is the image of a public philosopher. Socrates didn’t write articles. He didn’t publish in peer reviewed journals. He had conversations with members of his community about subjects that matter. The practice of public philosophy is thriving today in a surprising number of forms. Different approaches give rise to meta-level questions about the nature of philosophy in general and the nature of public philosophy in particular. I’ll provide a non-exhaustive discussion of some of these approaches and then I’ll discuss perks and pitfalls of one approach in particular.

One of the most common forms that public philosophy takes is work written for a broad audience rather than an academic one. Public philosophers of this type write articles for media outlets and blogs as well as books intended for consumption by non-specialists. This work relays information or offers arguments. One advantage of such an approach is that experts can (ideally) summarize a critical mass of information succinctly, making it possible for the community to get at the heart of a philosophical issue quickly. 1,000 Word Philosophy, for instance, presents enduring philosophical questions along with summaries of some of the most compelling answers on offer in easily digestible articles.

Another form that public philosophy can take is facilitating active engagement with the history of philosophy. Public philosophers of this type might host open talks and panel discussions with experts. They might put together community reading groups. In Italy, a group of public philosophers has put together a philosophy museum that is open to the public. This form of public philosophy emphasizes the enterprise as a great conversation taking place across the duration of human history.

The third type of public philosophy and the type that I’ll discuss at length here is the approach that brings communities together to facilitate important conversations. This occurs in many settings: street corners, libraries, coffee houses, pizza parlors, and this approach acknowledges the philosophical spirit in everyone: the ability to give and respond to reasons, the capacity to develop and react with apt emotions in particular circumstances, the potential to weigh evidence and evaluate the trustworthiness of sources, and so on. Community members are actively participating in crafting and critiquing arguments. My husband, Dr. Richard Greene and I have put on many such events. We call them “Ethics Slams.” We’ve discussed issues such as climate change, gun control reform, and cancel culture. We begin by presenting a list of philosophical goals and commitments and then proceed to moderate open mic public conversations. Read more »

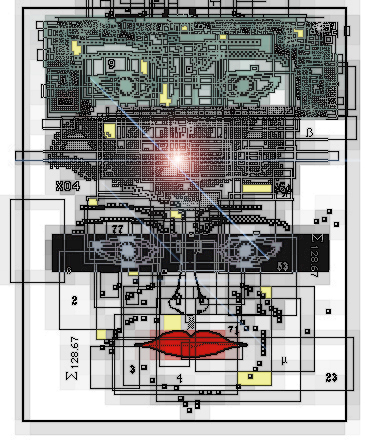

Sughra Raza. Approaching Washington, November 2024.

Sughra Raza. Approaching Washington, November 2024.

Oops. During most of 2024, all the talk was of deep learning hitting a wall. There were secret rumors coming out of OpenAI and Anthropic that their

Oops. During most of 2024, all the talk was of deep learning hitting a wall. There were secret rumors coming out of OpenAI and Anthropic that their

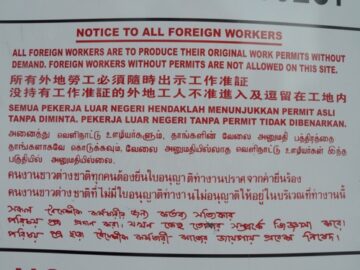

My great-grandparents were among the 12 million immigrants who passed through Ellis Island and equally a part of the wave of 20 million immigrants who entered the United States between 1880 and 1920. America’s fast-growing economy needed more manpower than its existing population had available, and the poorer classes of Europe were the beneficiaries including four million Italians (largely southern) and two million Jews.

My great-grandparents were among the 12 million immigrants who passed through Ellis Island and equally a part of the wave of 20 million immigrants who entered the United States between 1880 and 1920. America’s fast-growing economy needed more manpower than its existing population had available, and the poorer classes of Europe were the beneficiaries including four million Italians (largely southern) and two million Jews.

An empire, threatened on its flank, vents spleen

An empire, threatened on its flank, vents spleen

Some people use religion to get their life together. Good for them. I’m all for it. Although I myself am an atheist, I don’t think it much matters how someone gets their life together so long as they do.

Some people use religion to get their life together. Good for them. I’m all for it. Although I myself am an atheist, I don’t think it much matters how someone gets their life together so long as they do.

On the one hand, nothing has changed since August 2020, when I wrote

On the one hand, nothing has changed since August 2020, when I wrote