by Abigail Akavia

A group of young women performing exercises at the ballet barre and an angry mob chanting “lock her up.” These two situations, where the exact same action is performed by a group of people, may have more in common than it appears at first. Kinesthetic empathy, a recent topic of research for neurobiologists, dance theorists and a range of scholars and professionals in between, offers an interesting perspective on this issue, since it points to the emotional effect of physical activities carried out in group settings.

Empathy is a blanket term for a wide range of interpersonal phenomena: it is probably most commonly understood as an other-oriented feeling of concern or compassion. Empathy can also be defined as an ability to imagine what the other person is going through, or as an intuitive understanding of another person, including an understanding that is more physical than mental. Mirror neurons in the brain—for example, those firing both when we itch our foot and when we see someone else itching their foot—are probably involved in such a body-mediated and body-motivated awareness of the other.

It is remarkable that we can also feel empathy towards a fictional character, say in a book, a film, or in the theater. The latter situation is especially interesting because by understanding how audience members relate emotionally to what they see onstage we may gain access to how the audience as a gathering of disparate individuals becomes a group, a collective whose emotions and reactions can be manipulated and controlled. When the aesthetic medium is dance, the nexus of emotional reactions and physical experience is more obvious, even if not easier to parse; for it is through the body and without the mediation of words that we are “moved.” Read more »

Discussions of the factors that go into wine production tend to circulate around two poles. In recent years, the focus has been on grapes and their growing conditions—weather, climate, and soil—as the main inputs to wine quality. The reigning ideology of artisanal wine production has winemakers copping to only a modest role as caretaker of the grapes, making sure they don’t do anything in the winery to screw up what nature has worked so hard to achieve. To a degree, this is a misleading ideology. After all, those healthy, vibrant grapes with distinctive flavors and aromas have to be grown. A “hands off” approach in the winey just transfers the action to the vineyard where care must be taken to preserve vineyard conditions, adjust to changes in weather, plant and prune effectively and strategically, adjust the canopy and trellising methods when necessary, watch for disease, and pick at the right time.

Discussions of the factors that go into wine production tend to circulate around two poles. In recent years, the focus has been on grapes and their growing conditions—weather, climate, and soil—as the main inputs to wine quality. The reigning ideology of artisanal wine production has winemakers copping to only a modest role as caretaker of the grapes, making sure they don’t do anything in the winery to screw up what nature has worked so hard to achieve. To a degree, this is a misleading ideology. After all, those healthy, vibrant grapes with distinctive flavors and aromas have to be grown. A “hands off” approach in the winey just transfers the action to the vineyard where care must be taken to preserve vineyard conditions, adjust to changes in weather, plant and prune effectively and strategically, adjust the canopy and trellising methods when necessary, watch for disease, and pick at the right time.

On the morning of August 20, 1968, the Czech playwright Vaclav Havel had a serious hangover. He was at his country home in Liberec after a night of boozing it up with his actor friend

On the morning of August 20, 1968, the Czech playwright Vaclav Havel had a serious hangover. He was at his country home in Liberec after a night of boozing it up with his actor friend  by Leanne Ogasawara

by Leanne Ogasawara

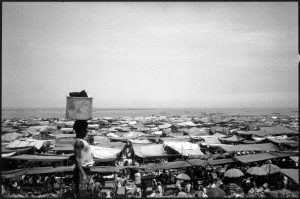

My wife and I took a peek into the interior of Papua New Guinea twenty years ago.

My wife and I took a peek into the interior of Papua New Guinea twenty years ago.