by Andrea Scrima

Americans are often smiled upon for their need to identify with their ancestors’ heritage; there’s something naïve and childlike about it, as though we were hoping to find a family somewhere, waiting with open arms for the long-lost child who has finally come home. We describe ourselves with the usual hyphenated ethnic adjectives, we say we’re one quarter this, half that, etc., but the truth is, we create fictional narratives to orient ourselves in a society too young to understand that the identities we claim often have little to do with the culture they purport to originate in. When I think about the cultural clichés we grew up with—the Italian mother leaning out of a tenement window, calling her son home to dinner in a 1960s television commercial; the way we gleefully mimicked her by crying out “Anthoneeeeeeeee!”—I recall the laughter and pantomime and how everyone understood what was meant. But what did it mean? That we were second generation, and thus not as “ethnic” as the old-world Italians portrayed—that we were not Anthony Martignetti racing home through the streets of the Italian north end of Boston on Wednesday, “Prince Spaghetti Day,” but were secure enough in our American identity to mock him? And that in spite of the fondness we felt for our cultural heritage, we’d been enlisted in the very racism that had been leveled at our parents, that had branded them as outsiders, and that had trapped them in a lower social status, a stigma that proved difficult to shed.

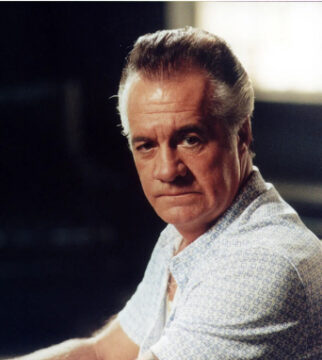

In an attempt to understand my relationship to the Italian-American identity, I recently began watching episodes of The Sopranos, which I avoided when it first aired twenty-five years ago. I was on a nine-month stay in New York at the time, living in a loft on the Brooklyn waterfront, and I remember the ads in the subways—the actors’ grim demeanors; the letter r in the name “Sopranos” drawn as a downwards-pointing gun. I’ve always been bored by the mobster clichés, by the romanticization of organized crime: as an entertainment genre, it’s relentlessly repetitive, relies on a repertoire of predictable tropes, and it has cemented the image of Italian Americans we all, to one degree or another, carry around with us. But the charisma of Tony Soprano, played by James Gandolfini, exerts an irresistible pull: I jettison my critical abilities and find myself binge-watching several seasons, regressing for weeks at a time, losing touch with what I was hoping to find.

In an attempt to understand my relationship to the Italian-American identity, I recently began watching episodes of The Sopranos, which I avoided when it first aired twenty-five years ago. I was on a nine-month stay in New York at the time, living in a loft on the Brooklyn waterfront, and I remember the ads in the subways—the actors’ grim demeanors; the letter r in the name “Sopranos” drawn as a downwards-pointing gun. I’ve always been bored by the mobster clichés, by the romanticization of organized crime: as an entertainment genre, it’s relentlessly repetitive, relies on a repertoire of predictable tropes, and it has cemented the image of Italian Americans we all, to one degree or another, carry around with us. But the charisma of Tony Soprano, played by James Gandolfini, exerts an irresistible pull: I jettison my critical abilities and find myself binge-watching several seasons, regressing for weeks at a time, losing touch with what I was hoping to find.

One day, in the midst of this period, I hear myself talking about the show to a friend, hear the Staten Island accent creeping back in. What part of me is becoming reactivated, what pleasure is there? And what pain? Old feelings of belonging to a kind of clan identity, of belonging somewhere, before that somewhere revealed itself as a fiction, before it became uninhabitable. I grew up with people like the Sopranos. When I was in high school, I babysat for a family who spoke just like the Sopranos, whose house looked a lot like the Sopranos’s, only smaller. They were all seriously overweight. The father would drive me home at night in his enormous Cadillac, and even though he himself was enormous, to my great relief a considerable distance still separated us on the front seat. When he paid me, the dollar bills smelled of his aftershave. I’m not sure if they were involved with the mob; they shared a surname with a politician who was charged with racketeering and went to prison a few years later, but I don’t know if they were family. Other mob-related memories: headed with my friend Sally to the local off-track betting office on Hylan Boulevard, where her father stood outside, next to the entrance. I see him pulling a grapefruit-sized wad of fifty-dollar bills out of his pocket, peeling several off, and handing them out to her, just like that. I had only seen people carrying wads of money around in their pockets in the movies. Sally was embarrassed that her father didn’t live at home, that he was in organized crime. I maintained a poker face for her sake, and although his criminality repelled me, I was also envious.

There’s been a lot of talk about how The Sopranos speaks to issues impacting women’s lives, for instance rape, prostitution, and domestic abuse. Due in large part to Gandolfini’s performance, the series is as popular today as it was when it first aired, yet disappointingly, there is little to no feminist perspective evident in the show’s portrayal of female characters. One senses—or perhaps it’s primarily women viewers who sense—that their parts were written by a male author; they’re given so little individual agency or room to be anything more than the roles they embody in relation to their men. With her sprayed hair, acrylic nails, and Catholic homilies, Carmela is the materialistic, status-minded, sexually neglected wife and dedicated mother; she acquires depth as the series progresses, but in the end, despite her religious trappings, she remains Tony’s enabler, keen on extracting as much wealth as she can before he’s offed. As for her mobster wife friends, they’re all makeup and hairdo and dressed to kill, but bafflingly gullible as to who is responsible when their husbands and sons go missing. And at the other end of the Madonna/whore continuum: of the pole-dancing Bada Bing! hookers with their surgically implanted breasts and platform shoes—who undulate in a manner so mind-numbingly uniform as to be curiously devoid of all eroticism—only one is portrayed as an individual, a doomed young woman from an abusive background whose most cherished dream is to get married and have a kid. Then there’s Gloria, the successful Mercedes dealer, who suffers from borderline personality disorder and is incapable of maintaining healthy relationships, while the mobster’s pampered daughter Meadow manages to compartmentalize everything she already knows about her father’s true line of business. Among the mob wives, Angie is the only one to achieve any real financial independence—but this is after she is left nearly penniless by her husband’s disappearance. Even the straight-talking Svetlana, a Russian immigrant with a prosthetic leg, comes across as typecast: she is the tough-as-nails, vodka-swigging Eastern European with a level head and few illusions.

There’s been a lot of talk about how The Sopranos speaks to issues impacting women’s lives, for instance rape, prostitution, and domestic abuse. Due in large part to Gandolfini’s performance, the series is as popular today as it was when it first aired, yet disappointingly, there is little to no feminist perspective evident in the show’s portrayal of female characters. One senses—or perhaps it’s primarily women viewers who sense—that their parts were written by a male author; they’re given so little individual agency or room to be anything more than the roles they embody in relation to their men. With her sprayed hair, acrylic nails, and Catholic homilies, Carmela is the materialistic, status-minded, sexually neglected wife and dedicated mother; she acquires depth as the series progresses, but in the end, despite her religious trappings, she remains Tony’s enabler, keen on extracting as much wealth as she can before he’s offed. As for her mobster wife friends, they’re all makeup and hairdo and dressed to kill, but bafflingly gullible as to who is responsible when their husbands and sons go missing. And at the other end of the Madonna/whore continuum: of the pole-dancing Bada Bing! hookers with their surgically implanted breasts and platform shoes—who undulate in a manner so mind-numbingly uniform as to be curiously devoid of all eroticism—only one is portrayed as an individual, a doomed young woman from an abusive background whose most cherished dream is to get married and have a kid. Then there’s Gloria, the successful Mercedes dealer, who suffers from borderline personality disorder and is incapable of maintaining healthy relationships, while the mobster’s pampered daughter Meadow manages to compartmentalize everything she already knows about her father’s true line of business. Among the mob wives, Angie is the only one to achieve any real financial independence—but this is after she is left nearly penniless by her husband’s disappearance. Even the straight-talking Svetlana, a Russian immigrant with a prosthetic leg, comes across as typecast: she is the tough-as-nails, vodka-swigging Eastern European with a level head and few illusions.

Of all the characters in The Sopranos, it’s the conflicted Dr. Jennifer Melfi, played by Lorraine Bracco, with whom I most identify. Tony Soprano begins seeing her in the hopes that she can help him with his panic attacks; she is the conservatively dressed, level-headed psychiatrist Tony tries but is unable to rile up or seduce. Over the course of the series, however, she begins to unravel. In sessions with her own therapist, she denies having sexual feelings for Tony but soon admits that she’s drinking. She defends her commitment to her patient, and when the therapist challenges the professional ethics of treating a sociopathic criminal, she becomes defiant and storms out of the office, mimicking Tony’s abrasiveness, his obscenities. She fears Tony, she despises him at times, but she cannot bear to end their sessions. Is he her link to a part of her upbringing that she left behind to get an education and embark on a medical career? She is one of many women who must learn how to blend into an academic or professional milieu, tone things down, resist the goombah clichés. How to smooth out the ethnic edges, the accent—it’s a performance, like being an American in drag. It’s required to blend in, to not trigger the Wasp elites with images of the fictional characters of The Godfather, A Bronx Tale, Goodfellas. As for myself, when I try out the mannerisms I grew up with, it’s also in drag: I am imitating an accent I no longer master, one that’s changed over time, grown foreign to me.

Of all the characters in The Sopranos, it’s the conflicted Dr. Jennifer Melfi, played by Lorraine Bracco, with whom I most identify. Tony Soprano begins seeing her in the hopes that she can help him with his panic attacks; she is the conservatively dressed, level-headed psychiatrist Tony tries but is unable to rile up or seduce. Over the course of the series, however, she begins to unravel. In sessions with her own therapist, she denies having sexual feelings for Tony but soon admits that she’s drinking. She defends her commitment to her patient, and when the therapist challenges the professional ethics of treating a sociopathic criminal, she becomes defiant and storms out of the office, mimicking Tony’s abrasiveness, his obscenities. She fears Tony, she despises him at times, but she cannot bear to end their sessions. Is he her link to a part of her upbringing that she left behind to get an education and embark on a medical career? She is one of many women who must learn how to blend into an academic or professional milieu, tone things down, resist the goombah clichés. How to smooth out the ethnic edges, the accent—it’s a performance, like being an American in drag. It’s required to blend in, to not trigger the Wasp elites with images of the fictional characters of The Godfather, A Bronx Tale, Goodfellas. As for myself, when I try out the mannerisms I grew up with, it’s also in drag: I am imitating an accent I no longer master, one that’s changed over time, grown foreign to me.

Another set of misunderstood identities is explored in a Sopranos episode in which Tony takes Paulie and Christopher along on a business trip to Naples. They meet with a family of the Camorra to propose an overseas car smuggling operation. To pay respect to their American guests, the hotel staff address them by the term “Commendatori” or “Knight Commanders,” a chivalric title originally introduced by the royal House of Savoy. The term leaves a deep impression on Paulie; he uses it with varying success as he takes his evening stroll. It’s an awkward episode: with their lack of language skills, their pretensions of being Italian, and again and again their “capeesh,” Tony and his men come across as clowns. Paulie seems to think that Italian cuisine consists exclusively of spaghetti and meatballs; when he is served a Neapolitan delicacy—squid-ink bucatini with mussels—he can no longer contain his disappointment and asks if he can’t just have “macaroni and gravy.” Someone has to translate, explain to the waiter that he means “tomato sauce.” A man sitting opposite Paulie at the dinner table smiles reassuringly and then, in an aside to his neighbor, remarks, “And you thought the Germans were classless pieces of shit.”

This is Paulie’s first time in the “Old Country”; he falls prey to his own sentimentality, expects Italy to return the love and embrace its long-lost son. Lying in bed post-coitus, Paulie tells a hooker impatient to put on her clothes and leave that he and Tony are “Napolitan,” but that some of the other guys are “Sicilians,” pronouncing the word in what he thinks is Neapolitan dialect and tacking on the English plural. The prostitute takes a drag on her cigarette and corrects him by repeating the word in proper Italian, underscoring his counterfeit identity. When he asks her where she’s from, she answers “Ariano Irpino.” Paulie responds with an astonished “You’re shitting me! That’s where my grandfather is from, il mio Nonno!” He sits up in bed, all smiles; he expects a reaction from her, he expects emotion of some kind. It’s his “Roots” moment, but she’s bored. Still under the spell of the coincidence, he continues: “We come from the same town, our families probably knew each other!” The prostitute shrugs; it’s over that way, she says, “è là,” nodding to the window, then scratches her foot. Paulie craves connection, an appreciation of the significance the moment holds for him. I sit in front of the screen, watching intently. Ariano Irpino is the town closest to Greci; it’s where Fabio lives, where the missed train from Foggia was supposed to take me. I press the pause button and think of myself sitting on a darkened bus in a thunderstorm and watching the blue dot on Google Maps approach the road that leads to my ancestors’ village. I feel ridiculous, exposed; Paulie is mirroring my own fantasies that Italy will open its arms to me, will finally recognize its wayward daughter and beckon her home.

This is Paulie’s first time in the “Old Country”; he falls prey to his own sentimentality, expects Italy to return the love and embrace its long-lost son. Lying in bed post-coitus, Paulie tells a hooker impatient to put on her clothes and leave that he and Tony are “Napolitan,” but that some of the other guys are “Sicilians,” pronouncing the word in what he thinks is Neapolitan dialect and tacking on the English plural. The prostitute takes a drag on her cigarette and corrects him by repeating the word in proper Italian, underscoring his counterfeit identity. When he asks her where she’s from, she answers “Ariano Irpino.” Paulie responds with an astonished “You’re shitting me! That’s where my grandfather is from, il mio Nonno!” He sits up in bed, all smiles; he expects a reaction from her, he expects emotion of some kind. It’s his “Roots” moment, but she’s bored. Still under the spell of the coincidence, he continues: “We come from the same town, our families probably knew each other!” The prostitute shrugs; it’s over that way, she says, “è là,” nodding to the window, then scratches her foot. Paulie craves connection, an appreciation of the significance the moment holds for him. I sit in front of the screen, watching intently. Ariano Irpino is the town closest to Greci; it’s where Fabio lives, where the missed train from Foggia was supposed to take me. I press the pause button and think of myself sitting on a darkened bus in a thunderstorm and watching the blue dot on Google Maps approach the road that leads to my ancestors’ village. I feel ridiculous, exposed; Paulie is mirroring my own fantasies that Italy will open its arms to me, will finally recognize its wayward daughter and beckon her home.

The clichés the series deals in also extend to the Italian identity: after her pedicure, the head of the clan, the imprisoned boss’s wife Annalisa, counts her toenail clippings to be sure the maid hasn’t stashed one away to use in some kind of malevolent spell against her. She later burns them. Annalisa is a powerful matriarch who runs the family business and reigns over a large brood of children, mobster underlings, and her senile father, yet she is portrayed as steeped in sinister Old-World pagan beliefs. She takes Tony on a day trip to the Cave of the Sibyl, said to be the site of the mythical Cumaean prophetess who presided over the Apollonian Oracle. In one of the series’ many misogynistic moments, Tony, who came on to Annalisa earlier, but without success, now rebuffs her advances. He doesn’t like that she has power, doesn’t like that she drives a hard bargain, and maybe, at this point, he’s spooked. He tells her he doesn’t shit where he eats; it’s his way of saying that he doesn’t want to mix sex and business. His instinct is telling him to remain on guard; the implication is that she’s a kind of siren, a witch whose seductive prowess threatens to spell the hero’s demise.

The clichés the series deals in also extend to the Italian identity: after her pedicure, the head of the clan, the imprisoned boss’s wife Annalisa, counts her toenail clippings to be sure the maid hasn’t stashed one away to use in some kind of malevolent spell against her. She later burns them. Annalisa is a powerful matriarch who runs the family business and reigns over a large brood of children, mobster underlings, and her senile father, yet she is portrayed as steeped in sinister Old-World pagan beliefs. She takes Tony on a day trip to the Cave of the Sibyl, said to be the site of the mythical Cumaean prophetess who presided over the Apollonian Oracle. In one of the series’ many misogynistic moments, Tony, who came on to Annalisa earlier, but without success, now rebuffs her advances. He doesn’t like that she has power, doesn’t like that she drives a hard bargain, and maybe, at this point, he’s spooked. He tells her he doesn’t shit where he eats; it’s his way of saying that he doesn’t want to mix sex and business. His instinct is telling him to remain on guard; the implication is that she’s a kind of siren, a witch whose seductive prowess threatens to spell the hero’s demise.

In the end, the character of Dr. Melfi is also sacrificed to a sexist trope: after her colleagues stage a thinly disguised intervention, she is compelled to read the recent literature on sociopaths and their purported immunity to the psychotherapeutic method. At what becomes her final session with Tony, she tells him, in an uncharacteristically sarcastic tone, that she is terminating their arrangement. Melfi has been rattled by what she’s read; apparently, she has so little trust in her own professional assessment and so little faith in her work that she caves in to her colleagues’ pressure. She betrays her own better judgment that Tony’s suffering is, in fact, genuine and that their therapy sessions of seven years have been meaningful. The show takes back all the power it gave to her character: we thought she was strong and dedicated to her work, but it turns out she’s been doing little more than sublimate her sexual desire. She is, like all women, inconsistent, lacking in confidence, and gratuitously cruel, and her unpredictable behavior only serves to confirm Tony’s view of the “weaker” sex.

One character is drawn uncomfortably close to home: although I’ve never joined an ashram, I see a distorted version of myself reflected in Tony’s older sister Janice. An unmarried “artist” who fled the family as soon as she could, she makes videos and gets by on side jobs and fly-by-night projects. Early in the series, we take her for a critical observer, a prodigal daughter whose role is to verbalize what everyone else can’t or won’t see. But we soon realize our mistake: instead of allowing a female character to achieve true creative autonomy, to feel a calling unrelated to marriage and children and excel in something, the show’s writers portray her as a ruthless grifter combing her mother’s basement walls with a metal detector, out to get her disability checks, her house, her squirreled-away fortune. We never experience Janice actually engaged in the all-absorbing task of creating serious work: she is a stereotype, her claim to being an artist the kind of sham siblings often suspect it is. Lazy, disinclined to work, she’s always on the lookout for a way to play the system; she confirms everything artists’ families have always thought of them. She goes from being Catholic to Buddhist to born-again Christian, which inspires her to her next get-rich-quick scheme: she’s learning the guitar to make it big in the Christian music industry. Instead of allowing her to be a successful émigré from the crime world, the show’s writers heap an entire mess of clichés on her. I try to imagine her role written differently; I try to imagine her enjoying a rich artistic life. Why does she go in for her high school boyfriend, the gangster Richie Aprile? Is this a believable character, and what does this tell us about how society views women in the creative fields?

One character is drawn uncomfortably close to home: although I’ve never joined an ashram, I see a distorted version of myself reflected in Tony’s older sister Janice. An unmarried “artist” who fled the family as soon as she could, she makes videos and gets by on side jobs and fly-by-night projects. Early in the series, we take her for a critical observer, a prodigal daughter whose role is to verbalize what everyone else can’t or won’t see. But we soon realize our mistake: instead of allowing a female character to achieve true creative autonomy, to feel a calling unrelated to marriage and children and excel in something, the show’s writers portray her as a ruthless grifter combing her mother’s basement walls with a metal detector, out to get her disability checks, her house, her squirreled-away fortune. We never experience Janice actually engaged in the all-absorbing task of creating serious work: she is a stereotype, her claim to being an artist the kind of sham siblings often suspect it is. Lazy, disinclined to work, she’s always on the lookout for a way to play the system; she confirms everything artists’ families have always thought of them. She goes from being Catholic to Buddhist to born-again Christian, which inspires her to her next get-rich-quick scheme: she’s learning the guitar to make it big in the Christian music industry. Instead of allowing her to be a successful émigré from the crime world, the show’s writers heap an entire mess of clichés on her. I try to imagine her role written differently; I try to imagine her enjoying a rich artistic life. Why does she go in for her high school boyfriend, the gangster Richie Aprile? Is this a believable character, and what does this tell us about how society views women in the creative fields?

We watch them get raped, battered, maimed, and killed; we watch them commit suicide or remain trapped in their learned passivity. The mobster wives, in a kind of pseudo-feminist gesture, wage a stereotypical suburban “war of the sexes” in which the men are criticized for their dedication to TV sports, for the trail of dirty socks they leave behind, for the unwashed plates in the sink. Only Janice strikes back by killing the man that physically abuses her—but this is portrayed less as an act of self-preservation than as evidence of her own innate criminality. She is, after all, the boss’s daughter: violence is in her blood.

The Sopranos has been said to unpack and challenge the power structures of patriarchal abuse—but by depicting it in evocative ways and with charismatic characters, the series also perpetuates the pattern. How could it not? While the sexual politics on display mirror gender roles in the Italian-American community and much of the rest of society, they also reflect it back to the show’s viewers as a plausible reality, as something to emulate. Paradoxically, women enjoy the series as much as men, devour it like a guilty pleasure, find themselves entertained by things they would never want or tolerate in their own lives. But perhaps there’s some other instinct at work, an understanding that the male characters don’t fare all that much better, that they’re trapped in a crisis of masculinity. Grappling for status, forced to subject themselves to the humiliations of the mob family hierarchy, to pay “respect” in a highly ritualized sado-masochistic social order in which homoeroticism is the hotly denied flip side of homophobia, they mistrust one another, second-guess one another. The Bada Bing! strip club offers them refuge: here they can feel in charge, take out their frustrations on the women, imagine themselves on top and not at the boss’s beck and call. Underdogs with little to no education—their ongoing mispronunciation of words they’ve heard somewhere but have never seen in written form constitutes a leitmotif all its own—they are caught in a world that offers them few alternatives. If Italian-American families have traditionally produced blue-collar workers, and organized crime is seen by some as a step up in power and mystique, the life these men have chosen turns out to be crueler than the wage-earning labor they despise. For the most part, the men in The Sopranos are petty criminals desperate to prove themselves, men with few options, men who have maneuvered themselves into a corner where the only way to survive is violence and the only way out either prison, witness protection, or death. The Sopranos sheds light less on the glamorous life of the fabled Italian-American gangster than on the male anxieties of the immigrant working class—and how women pay the price for men’s feelings of inferiority, for their resentment and rage.