by Barry Goldman

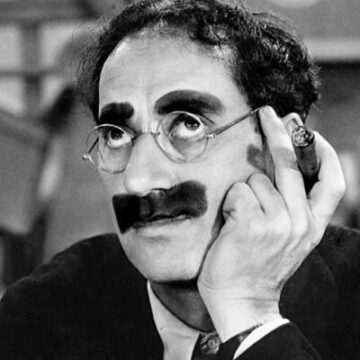

Those are my principles, and if you don’t like them… well, I have others. —Groucho Marx

It’s easy to ridicule politicians for their lack of principle. Mitch McConnell comes immediately to mind. When Antonin Scalia died nine months before the 2016 election, President Obama nominated Merrick Garland to replace him on the Supreme Court. McConnell refused even to give Garland a hearing. He said, “The American people may well elect a president who decides to nominate Judge Garland for Senate consideration. The next president may also nominate someone very different. Either way, our view is this: Give the people a voice.”

Four years later when Ruth Bader Ginsberg died 47 days before the 2020 election, President Trump nominated Amy Coney Barrett. The voice of the people did not figure in McConnell’s calculations. He fast-tracked Barrett’s nomination, cut off debate, and engineered her confirmation eight days before the election, after millions of Americans had voted.

Predictably, there were loud cries of hypocrisy. Just as predictably, they had no effect. The universe of politicians is not a good place to look for moral principle.

How about the courts? The whole idea of the rule of law is that laws are supposed to be based on principle, applied without fear or favor, and above politics. The reality, of course, is otherwise.

In the Dobbs case overruling Roe v. Wade, Justice Alito wrote that the Court, “cannot allow our decisions to be affected by any extraneous influences such as concern about the public’s reaction to our work.”

Then, in Trump v. Anderson, the 14th Amendment disqualification case, the Court said if it allowed Colorado to disqualify Trump, the “disruption” would be “acute” and “Nothing in the Constitution requires that we endure such chaos.”

Similar self-contradiction is everywhere. Textualists claim to be strictly applying the plain meaning of the text. And sometimes they do that. But not when the text – as in Section 3 of the 14th Amendment – plainly, clearly, and unambiguously calls for something they don’t want.

When I was in law school, we learned the Supreme Court will not consider any matter unless there is a real “case or controversy” with a real plaintiff and actual harm. No hypotheticals, no speculation. We also learned about “judicial restraint.” As Justice Roberts would later put it, “If it is not necessary to decide more to dispose of a case, then it is necessary not to decide more.” The Supreme Court has always rigorously applied these principles. Unless they have the votes, and there is something they want to do.

In 303 Creative the court decided a woman who had never designed a website for any kind of wedding wouldn’t have to design one for a gay wedding if she didn’t want to. The issue was completely hypothetical, and the ruling made a mockery of judicial restraint. But the Court went ahead and did what it wanted to do because if you have the votes, nothing else matters. Not the law, not the facts, not precedent, not history. The dissent pointed out, “the Court, for the first time in its history, grants a business open to the public a constitutional right to refuse to serve members of a protected class.” It is not a coincidence that the class in question is gay people. The majority of the court disapproves of gay people. That’s all there is to it. If we are looking for principle, we’re going to have to look elsewhere.

None of this is terribly surprising. Politicians are politicians. And members of the court, alas, are politicians too. But if we are going to criticize the Alitos and McConnells of the world, we are going to have to demonstrate that we are not guilty of the same hypocrisy. That may not be so easy.

Take the case of voter suppression. Folks on my side of the debate like to say Republicans are afraid of voters. They know their positions on issues like gun control and reproductive rights are unpopular. If the question of access to medication abortion or regulation of assault weapons were freely and fairly presented to the voters, the Republicans would lose. They know that. They also know they can rely on their highly motivated base. So they try to restrict voting by people who are not members of that base.

Of course, they can’t say that out loud. They can’t say, “We are trying to make it hard for Black people and young people to vote.” They need a cover story. They have to pretend to care about something called “voter fraud.” There is no such thing in the real world. The number of actual cases of voter fraud is effectively zero, but that’s not the point. If you say you are concerned about voter fraud you can use that excuse to impose measures that achieve your real objective – making it more difficult for the opposition to vote.

Well, they can’t fool me. I see what they’re doing. And I support all the efforts to make it easier to vote. I think there should be same-day registration and automatic voter registration issued with driver’s licenses and mail-in ballots and absentee ballots on demand and more polling places and longer hours. And if I could think of other things that would make voting easier I would support them too.

Why? Because I believe in democracy and the voice of the people.

Fine. Very high-minded. But let’s push back on that a little. Suppose I learned that, contrary to my previous understanding, higher voter turnout favors Trump. The more people who vote, the greater the likelihood that Trump gets back into the White House. Whatever it takes to convince me of that, suppose I’m convinced. Now what?

I know my answer. If I thought higher turnout favored Trump, I would instantly and fervently transform into a voter suppressionist. I would oppose everything I formerly supported and support everything I formerly opposed. And I would do it vehemently.

But what has become of my principle? My belief in democracy? And, most painfully, what is the difference between me and Alito or me and McConnell?

I have two answers to propose. Neither is satisfactory. The first one comes from the evolutionary psychologist Rob Kurzban. In his book Why everyone (else) is a hypocrite, Kurzban says the brain is modular. Different regions evolved to solve different problems. There is no unified self, it just seems like there is. What appears to be self-contradiction goes away if we abandon the idea of the self.

Susan Blackmore reaches the same conclusion in her fascinating book, The Meme Machine:

Whatever the brain is doing it does not seem to need help from an extra, magical self. Various parts of the brain carry on their tasks independently of each other and countless different things are always going on at once. We may feel as though there is a central place inside our heads in to which the sensations come and from which we consciously make the decisions. Yet this place simply does not exist.

Interesting, maybe even true, but hard to believe. Something like Robert Sapolsky’s view that there is no free will.

The second proposal comes from Bertrand Russell:

Every philosopher, in addition to the formal system which he offers to the world, has another, much simpler, of which he may be quite unaware. If he is aware of it, he probably realizes that it won’t quite do; he therefore conceals it, and sets forth something more sophisticated, which he believes because it is like his crude system, but which he asks others to accept because he thinks he has made it such as cannot be disproved.

In this view, my professed belief in democracy is a fig leaf. It is produced for external consumption. My real view is much more crude. It is the belief that Trump is a uniquely dangerous psychopath, and preventing him from getting back into the White House is more important than anything else we could be doing.

I don’t like this idea either. If I get to abandon my “principles” whenever I determine they have become sufficiently inconvenient, the concept loses its meaning. And I can’t criticize people like Alito and McConnell for being hypocrites. But there it is.