by Rebecca Baumgartner

It feels like every week tech journalism brings us a dispatch about the “end” of something: we’re told now that we’re reaching the end of foreign-language education due to advances in AI translation.

It’s true that no field of study is immune from journalistic swagger about our AI-saturated future, but this seems especially true for the arts and humanities, which have been said to be declining for a long time – and which, because their defenders struggle to articulate a compelling ROI, make them appear, to some people, ideal for outsourcing. According to this view, learning French is on a level with monotonously picking orders in a warehouse: If nobody wants to do it, let’s make the AI do it. And it seems that fewer and fewer of us want to learn French – and most other languages, too.

I think the world would be a better place if no human being had to pick orders in a warehouse ever again. By all means, let the robots knock themselves out trying to optimize how quickly we get our Amazon orders. They don’t have a soul to crush. But unlike the rote, mindless work that many humans currently have to do to make a living, creating and enjoying culture isn’t a burden we should rush to relieve ourselves of. Cultural products are not something that can – or should – be optimized in the way that AI models (and the humans behind them) lead us to believe they can.

By the way, it’s important to note that this has nothing to do with whether AI language models can translate a given text “correctly” (however that’s defined for a given text). It’s not even a question of whether the resulting translation is good or not, according to some normative standard of eloquence or naturalness.

Nor is it a matter of whether we can tell when a particular text was translated by AI or by a human; the value of cultural artifacts does not rest on a determination of how skilled we are at seeing through the tissue of artifice that went into making them. (If humans can see the Virgin Mary on a piece of toast, then the fact that we can be fooled into perceiving a mind behind a piece of AI writing says less about the power of the technology and more about the overly sensitive meaning-making and pattern-spotting abilities of the human mind.)

These issues are interesting and worth discussing, but they are not my primary focus here, which is to examine the value we accrue from the process of creating, learning, acquiring skills, and stretching ourselves – the kind of process involved in learning a foreign language – and what we lose when we waive the labor and joy of this process by deferring to AI tools. I believe the value of undertaking such projects is irreplaceable.

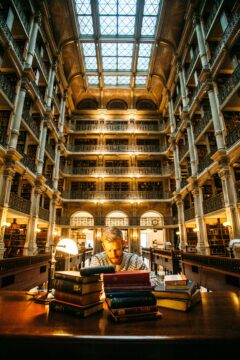

Learning as a Process of Unselfing

In her book The Sovereignty of Good (1970), philosopher Iris Murdoch describes foreign-language learning as one example of an “unselfing” activity, something that, like the enjoyment of art, “transcends selfish and obsessive limitations of personality” and takes us out of the “recognizable and familiar rat-runs of selfish day-dream.” Writing about learning Russian, she says:

“…I am confronted by an authoritative structure which commands my respect. The task is difficult and the goal is distant and perhaps never entirely attainable. My work is a progressive revelation of something which exists independently of me. Attention is rewarded by a knowledge of reality. Love of Russian leads me away from myself towards something alien to me, something which my consciousness cannot take over, swallow up, deny or make unreal. The honesty and humility required of the student – not to pretend to know what one does not know – is the preparation for the honesty and humility of the scholar who does not even feel tempted to suppress the fact which damns his theory.”

We might also add that such honesty and humility in the face of something outside oneself is also a preparation for the honesty and humility required to be a person who doesn’t succumb to despair or evil.

This may sound overblown, but it’s something I think we should take seriously. This is because, in Murdoch’s words, “Developing a Sprachgefühl [an intuitive feel or instinct for language] is developing a judicious respectful sensibility to something which is very like another organism.” Learning a foreign language – like learning a musical instrument or any number of other skills that bring us in contact with the world – demands that we set aside the “anxious avaricious tentacles of the self” and submit to a structure and community of which we can become a part, if we pay close enough attention.

This doesn’t have to be as austere as it sounds. In fact, it’s electrifying; it’s about love. It’s about quieting our frenzied selfishness to instead see what’s really out there, what this other “organism” of the unfamiliar language has to show us. The willing submission to a body of knowledge is a kind of “undogmatic prayer” that stretches “between the truth-seeking mind and the world.” This is possible because for Murdoch (as for me), intellectual disciplines are also necessarily moral disciplines:

“In intellectual disciplines and in the enjoyment of art and nature we discover value in our ability to forget self, to be realistic, to perceive justly. We use our imagination not to escape the world but to join it, and this exhilarates us because of the distance between our ordinary dulled consciousness and an apprehension of the real.”

Taking it even further: If you zoom out far enough, learning anything at all has no point. It’s not as though the world cares whether we understand it or not. But the ultimate pointlessness of learning any particular thing, far from being a source of despair, should be a source of pleasure to us.

If you accept this as true, then questions like “What will I ever use this for?” or “How much will learning this increase my earnings?” are irrelevant. Or as the author of the “end of foreign-language learning” piece put it, “[AI video-generator HeyGen’s] language technology is good enough to make me question whether learning Mandarin is a wasted effort.”

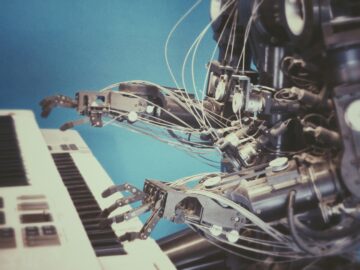

That mindset is the opposite of prayer and the opposite of learning; it’s a demand to drag that which is outside of us back into the rat-runs of selfish daydream, and it’s a demand we should resist. Instead (and much more enjoyably), we get a “self-forgetful pleasure in the sheer alien pointless independent existence” of whatever the object of our attention is – Russian, math, the piano, birds, stars, trees. Practicing our chosen art “affords us a pure delight in the independent existence of what is excellent…it invigorates our best faculties and, to use Platonic language, inspires love in the highest part of the soul.”

But Murdoch’s delight in what is excellent doesn’t necessarily have to be some sort of glorification of the lonely individual achieving greatness above a sea of mediocrity. It can and should be brought down to earth a bit and integrated with our role as social beings. As writer Matthew Crawford puts it in his book The World Beyond Your Head (2015):

“…membership in a community is a prerequisite to creativity. What it means to learn Russian is to become part of the community of Russian speakers, without whom there would be no such thing as ‘Russian’…These communities and aesthetic traditions provide a kind of cultural jig [in the sense of a device that guides the operation of a tool], within which our energies get ordered.”

Handing over to artificial minds the creativity that invigorates our best faculties and orders our energies within a community, merely for the sake of convenience (or to avoid “wasted effort”), comes with a price that we may not be able to predict and will very likely regret paying. If we skip out on French class and just let Google Translate or ChatGPT or DeepL or HeyGen handle foreign languages for us, we might find certain things easier, but we will also give up an opportunity to engage with the world and experience life outside our heads, and thereby create more interesting, more loving, more honest, and less selfish versions of ourselves.

Who Makes the Map and Why?

Despite the foregoing rallying cry, I take it as a near certainty that our society will continue to relegate more and more life-affirming tasks to AI so that we can reserve only the most soul-crushing ones for ourselves.

If and when we eventually use a universal translator to do the dirty work of conjugations and cross-linguistic understanding for us, we risk losing a skillset that we may be taking for granted. Putting aside the philosophical argument for a moment, even when learning a foreign language doesn’t feel enriching or life-expanding, it could be worth persisting in for compelling reasons we don’t yet know, because we can’t fully predict how the use of a certain technology will affect the way we think and act in the future.

One domain in which this process is already playing out is our rapidly diminishing understanding of local geography due to our reliance on ubiquitous GPS technology. “Passive navigation processes,” such as using Google Maps to get around, flatten and oversimplify our understanding of the geographical features and waypoints in our area. “In this way,” write the researchers of a 2019 study about how mobile maps have changed our perceptions of geography, “mobile maps discourage users from thinking and learning about the area around them.”

The idea that mobile map technology causes us to fail to notice and learn things about our immediate environs is distressing enough, but it gets even darker. It’s not just that we’re gradually losing a skill that humans have evolved for very good reason and might still need to keep sharp; it’s also a question of what that fading knowledge is being replaced with and who benefits from its degradation. In the situation described within the study, our intuitive grasp of navigation is being replaced, in part, with a representation of our environment that is anchored in and shaped by corporations – specifically, Starbucks. According to the researchers:

“mobile device map users frequently referred to a particular business, a Starbucks location, in a location-finding task…the map application providers’ business strategies, chiefly advertising, lead to an emphasis on business-type points of interest in mobile maps, which could shape users’ subsequent geographic knowledges. This has implications not only for mobile device use, but how technology companies’ maps potentially affect everyday understandings of the world around us.”

In other words, the cognitive processes involved in orienting ourselves in the world are being shaped in part by the market saturation of a particular corporation and visual portrayals of that market saturation on a map. The researchers noted that users of Google Maps or Apple Maps were making sense of the world around them by “seeing cartographic points of interest that are framed and presented to fit the mapmaker’s economic imperatives.” One study participant, who had been asked to use Google Maps to navigate to a university library, was quoted as saying, “I searched for Starbucks because I knew that would probably come up faster than the specific library.”

Perhaps not everyone will be bothered by this, but I find it deeply disturbing. I would like to believe that the places and landmarks I see on a map are presented to my view because they are objectively worth my navigational attention, not because the company in question exerted financial pressure to render the map into their own personal billboard. The study’s authors are clear-eyed about what this could eventually lead to:

“The next logical step is placing location-based ads within directions. Much like ads on the map, businesses could pay to place an advertisement within your directions whenever you happen to be driving by a franchise.”

Perhaps, one could argue, ads in maps aren’t such a big deal. But as the Starbucks study shows, we have evidence that the way tech companies choose to represent the world around us is already affecting how we perceive the world. The researchers also mention another app, this one by Microsoft, that used local data to route travelers around “undesirable” neighborhoods. While we don’t know exactly how Google and Apple (for example) turn their financial priorities into code on the back-end, we do know that businesses and their revenue potential for Google and Apple are a central part of the map design, particularly in the context of “ranking algorithms [“promoted places”], de facto urban racial segregation, third-party software developers, and geodemographic targeting.”

Likewise, when AI tools translate a text for us, it’s worth questioning whether and how the economic imperatives of companies like OpenAI and Google shape and constrain a particular translation which is presented to us as “the” translation for the text we inputted, passing unquestioned under the aegis of mega-corporations that we’ve gotten used to interacting with and therefore give the benefit of the doubt.

It doesn’t take a huge leap of logic to imagine how our knowledge of other languages and cultures, if subordinated carelessly to AI translation models, could eventually be commandeered by corporate interests – for example, by prioritizing some translations, interpretations, or linguistic choices over others based on criteria we would not choose for ourselves, assuming we had allowed ourselves to have a say in the matter.

It’s even plausible to imagine a time when the major language learning apps advertise on particular generative AI tools (or vice versa). I for one don’t relish the idea of the cartoonish Duolingo owl popping up to offer me a deal on a premium subscription while using Google Translate. Another way this scenario could operate in the realm of foreign language translation is that paying users of a particular third-party language app could be given access to translations pulling from larger or better-quality data sets compared to regular members of the public, introducing unequal levels of access to what is arguably a kind of public utility.

Language is political, technology is political, and both are embedded in economic systems, and it’s naive to pretend that a combination of the two will ever be, or remain, value-neutral. Maps reflect the financial priorities of the mapmaker.

Incidentally, this gives the lie to the facile platitude that technology is “just a tool” and that it’s up to us to choose whether to use it for good or evil. This is true up to a point, or when describing some Platonic ideal of technology to a young child, but in reality, that moral choice has often already been made for us without our awareness or with our tacit agreement. Who actually reads EULAs and T&Cs? Do you recall giving permission to Google Maps to show the Starbucks icon more prominently on your maps whenever you look up directions? Do you remember agreeing to let Google Maps monetize your navigational data? Odds are you did, whether you’re aware of it or not.

Calling these technological behemoths “just a tool” that we choose to use for good or evil places too much of the moral responsibility on individuals instead of corporations, who stand to benefit when we rush through these types of choices or have no other option but to acquiesce if we want to function in the modern world. In the words of the authors of the map study: “Users have some flexibility in what they do with a technology, or a map, but their actions are delimited by the built-in material structure created by the designer.”

At the very least, this Starbucks-as-landmark scenario should give us pause before we thoughtlessly surrender the practice or development of a particular skillset to a corporation performing a public service via proprietary technology – especially a relatively nascent and unregulated technology like generative AI, which cannot explain why it makes the choices it does, cannot be held accountable for the information it offers, and is operating under the economic incentives of giant tech companies that view the “informational heritage of humanity,” which we all helped build, as a source of private profits.

The Language of Russian Serfs

This is of course not to say that human translators and foreign-language learners are bias-free; but their biases are unlikely to be influenced by multi-trillion-dollar conglomerates, and are presumably no worse on average than the biases that all of us strive to overcome in the course of our respective jobs and lives. A certain “bias allowance,” honed over millennia of evolving social intelligence, is baked into our interactions with other people. We don’t yet have the cognitive immune system to recognize all the new and different ways that AI models are biased and fallible. As philosopher Daniel Dennett has pointed out, “Artificial people will always have less at stake than real ones, and that makes them amoral actors.” We’re not equipped to know how to deal with amoral actors; we’re too quick to trust anything that looks like it has a mind. Just ask Ginny Weasley.

Human translators will also generally have good reasons for making the particular literary or linguistic choices they make and can explain those reasons to us in satisfying ways, whether we agree with them or not. They can also offer sensible explanations for any errors they make (like the mistranslation of sapere aude I wrote about previously, which, though disappointing, is an immanently understandable mistake, in that you can see the through-line of how audere was mistaken for audire). Large language models and the tools that use them, by contrast, are trained to be bullshitters. They’ll make up a reason if we ask for one, but it will be disconnected from anything real.

Any human translator worth their salt would be willing and able to tell us exactly why they made the choices they did – in fact, pugnaciously defending particular translation choices seems to be the main reason for getting into the field of translation in the first place. To take just one example: While trying to decide which English translation of Gogol’s Dead Souls to read, I came across multiple somewhat rarefied but fascinating debates about all the various socio-political factors (in addition to the normal linguistic ones) that go into translating 19th-century Russian literature into English. For example:

“If you [the translator] have a rule that a Russian serf can’t sound like an American slave, you’re doing more than preserving an illusion of Russianness – you’re also passively asserting that serfdom is unlike slavery (just as using ‘serfdom’ instead of ‘slavery’ to describe the system does). This is especially true if the translated Russian slaves speak in the voice of free but poor northern whites or Englishmen…To me it seems like you either have associations with a particular non-Russian set of people, or you have bland universality….Can you make an American reader respond to the speech of 1850s Russian serfs the way she would respond to the speech of 1850s American slaves, without her feeling something’s out of place?”

This is not only not the type of question an AI translator (or its human chaperones) would ever think to ask, but it is also by no means certain that an appreciation for the necessity of answering it, much less the ability to come up with a valid answer, is within the power of such technology. Good luck getting an AI translator to coherently explain why they did or did not choose to have Russian serfs use the word “ain’t” in the English version. These are the kinds of issues human translators think deeply about, because they know such issues matter. They’ll differ on what they think is best, but they will at the very least have some kind of coherent opinion on the matter and a rationale to back it up. AI translation tools aren’t even aware there’s anything up for debate in translating 19th-century Russian literature, much less contributing to that debate.

You’ll often hear the word “frictionless” used to describe the goal of AI translation. In this view, we shouldn’t be able to sense the “friction” between languages; the reading comprehension task should be as silky as a dolphin, all signs of contact between different linguistic systems and their accompanying cultural meanings smoothed out to the point that we don’t know we’re reading a translated text. This goal is presented as a default, as though of course we all want to forget that there is anything foreign about what we’re encountering.

But this goal of frictionless contact is only one possible stance out of many. Some human translators aspire to this frictionless form of translation, and others don’t. This is the tension described above between the various options for representing Russian serfs and the language they use: One option is to present Russian serfs as though they are something socially equivalent in the target language, such as English peasants or American slaves – something familiar to an English-speaking reader. A second option is to create a “bland universality,” an Everyman that inhabits a made-up world that looks like Russia but where the people just so happen to speak English and we all agree to pretend there’s nothing weird about this. A third option is to preserve as much of the characters’ “Russianness” as possible – this is probably the option with the most “friction” because it is most unfamiliar. The particular context of a story and each translator’s preference should determine which option (or combination of options) is used, but each one comes with its own trade-offs.

We shouldn’t necessarily assume that when an AI translates something with the “friction dial” turned all the way down, this means the translation is better or more accurate. Maybe a little bit of friction is good. Language encounters, to say nothing of the complexities of the text itself, necessarily entail some amount of friction, and smoothing it all away could leave us with a beautiful falsehood.

When explaining why he made a translation choice that rendered a particular sentence clunkier and less elegant, Slavic scholar and translator Robert A. Maguire said in his 2002 article Translating Dead Souls: “It is not pretty, but it is more accurate…a conscientious translator must be willing to sound ugly or stumbling when the Russian dictates it.” Notice that he said “when the Russian dictates it” – this is exactly the submission to the real that Murdoch spoke of in her own language-learning. This is undogmatic prayer and unmasochistic humility. This is, in Murdoch’s words, “the disciplined overcoming of self.” Learning and humility go together because there is so much we don’t know. She goes on to say, “Humility is not a peculiar habit of self-effacement, rather like having an inaudible voice, it is selfless respect for reality and one of the most difficult and central of all virtues.”

AI tools do not have this selfless respect for reality; there is no reality, there is only data and those trained on it. Part of what it means to be a bullshitter is not admitting or caring about what is unknown. Instead, the bullshitter is indifferent to the very goal or idea of truth; it’s just saying stuff, and whether you choose to act on that or not makes no difference to it.

It’s not clear to what extent we’ll ever get explanations of why a given AI model chose one translation option over another, or what criteria went into making that choice. Nor is there a guarantee that a translation of the same text from one (identical) prompt to another will be consistent or logically predictable. There is no coherent worldview or philosophy of language driving these decisions, and readers are forced to take each offered translation at face value. As long as this is the case, AI translation efforts should be confined to surface-level transactions like translating a food label to make sure you’re not accidentally buying goat milk at the Bioladen. Not that they are being confined in this way, of course. As usual, our easily bestowed trust is outstripping the degree to which the technology has proved itself worthy of that trust.

It’s also unclear to what degree the black-box nature of AI translation is a feature or a bug – in other words, how much of it is due to the expected limitations of an artificial mind using natural language, versus how much of it is due to Google, OpenAI, etc. deliberately wanting to keep the recipe of their secret sauce a secret. We’re not sure to what extent the limitations of the system are artificial (so to speak) and thus hypothetically optional, and to what extent they are inherent to the system. (This is also unknown in the case of how mobile maps get developed, by the way.)

This is one of the dangers of relying on the good intentions of companies providing services that are increasingly used as public utilities. A service that presents itself as objective, such as a map or a translation service, yet is functioning, at least partially, according to self-serving ends (or shareholder-serving ends), should worry us.

The Professional Smile and the Anonymous Lover

David Foster Wallace, in his essay “A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again,” describes the corrosiveness of this kind of self-serving dishonesty in terms of an advertisement that pretends to be art:

“An ad that pretends to be art is – at absolute best – like somebody who smiles warmly at you only because he wants something from you. This is dishonest, but what’s sinister is the cumulative effect that such dishonesty has on us: since it offers a perfect facsimile or simulacrum of goodwill without goodwill’s real spirit, it messes with our heads and eventually starts upping our defenses even in cases of genuine smiles and real art and true goodwill. It makes us feel confused and lonely and impotent and angry and scared. It causes despair.”

Inadvertently touching on what makes conversations with AI chatbots feel so boring and frustrating and uncanny all at once, Wallace continues by saying, “This is the reason why even a really beautiful, ingenious, powerful ad (of which there are a lot) can never be any kind of real art: an ad has no status as gift, i.e., it’s never really for the person it’s directed at.”

An AI translation, unlike a human-created translation, also lacks this status as “gift.” It is not for anyone; it is not offered, rather it is summoned from the swirling void of linguistic corpora and other people’s intellectual property (often used without attribution). It’s the linguistic equivalent of the eerily fake “Professional Smile” which is compelled by the boss rather than offered sincerely, and which Wallace writes about in the context of service sector employees, or like a conversation with a chatbot trained to sound like a deceased loved one. The intended audience could be anyone, and therefore is no one.

We find this unsatisfying because we crave particular perspectives, not allocentric ones, in our interactions with other people. The specific individuality of our interlocutor is a necessary part of what makes them worth listening to and interacting with in the first place. It implies that what we say to them and what they say to us might matter in a real way in terms of affecting something in the world beyond our conversation. A conversation with an amoral Generic Mind can’t do this, even aside from philosophical debates about whether the Generic Mind can truly understand the language they’re using or not. Even if we grant that they can “understand” natural language and are not just stochastic parrots, what they say is untethered by real-world context and their role in it, which is the main thing about communication between different minds that makes it worth having.

This idea of individual discourse being plastered over with responses that could be directed to anyone (and therefore are directed to no one) is a hallmark of the de-personalization foisted on individuals which Søren Kierkegaard referred to as “leveling.” AI translations – similar to street signs, advertisements, public service announcements, or Google Maps that subconsciously train you to orient yourself relative to the closest Starbucks – are maximally leveled.

In The World Beyond Your Head, Crawford quotes Kierkegaard as saying, “Nowadays one can talk with any one…yet the conversation leaves one with the impression of having talked to an anonymity.” He goes on to say that when we converse with such an anonymity, our exchange of ideas is “so objective, so all-inclusive, that it is a matter of complete indifference who expresses them.” He makes a joke about what this looks like when taken to extremes: “In Germany they even have phrasebooks for the use of lovers, and it will end with lovers sitting together talking anonymously.” The idea of a lover – that supreme example of a particular, irreplaceable, irreducible other – speaking to us anonymously, failing to see our particularity, as though we were just anyone, rightfully gives us chills.

As I’ve argued before, this is the leveling we’re seeing play out with AI chatbots and other similar tools. Utterances taken from a cross-section of massive training data erase the sense of being directed from a particular, situated consciousness toward another particular, situated consciousness, which is a necessary ingredient for conversation, art, love, creativity, and community.

An anonymous stochastic parrot wearing a Professional Smile is not a conversation partner. Or a translator, or an artist, or a musician. We’re getting predictive accuracy and being told it’s intelligence. We’re getting anonymity instead of particularity, a phrasebook for lovers instead of the spontaneous exchange of ideas, ads instead of gifts, self-serving bullshit instead of a shared commitment to seeing reality and being honest about what is still unknown.

And as Wallace prophesied, if we continue treating these substitutes as though they’re the real thing, eventually we’ll become insensitive to “genuine smiles and real art and true goodwill” – which of course leads to despair.

A Fun Thing We’ll Supposedly Never Have to Do Again

Speaking of despair, and how creating and enjoying art is one of the most reliable ways we have of keeping it at bay, isn’t it strange that we want to outsource cultural creation to AI models at all? Doing so feels a bit like hiring someone to go on vacation for you.

The point of literature or painting has never been to churn out more poems or more paintings just for the hell of it, although that is the assumed rationale whenever we ask an artificial mind to create another piece of art. We forget that the generative process of creating art is an end unto itself.

Instead, we’re obsessed with how high the trained circus animal can jump. How do we get it to jump even higher? What other cool tricks can it do? Can it deceive music scholars into thinking a piece of music it created was written by Bach? If it can, why should humans bother to compose anything anymore? Why take Mandarin lessons if a video-generation site can make the world think you already know Mandarin? (You were only learning it to make people think you knew it, right?)

I think this is entirely the wrong approach when it comes to the activities that are most meaningful to us. Asking “Why should I learn a foreign language if I can just use Google Translate?” assumes that the point of translation is to be able to do it more quickly or efficiently, or that the value of this kind of knowledge consists of getting solutions to transactional problems. This may be true in certain trivial use cases. But it profoundly misses the point of art and cultural creation, which is, as Murdoch so rightly explained, a powerful and indispensable process of unselfing that “reveals to us aspects of our world which our ordinary dull dream-consciousness is unable to see.”

The question I think we should be asking instead is: What do we lose (and who gains from that loss) when we abandon these ideals and think purely in terms of wasted effort? The very simple answer is that I think we lose a valuable opportunity – maybe a uniquely valuable opportunity – to move ourselves closer to a recognition that we are not the center of the universe. Intellectual projects are worth our time and energy despite the presence of automated shortcuts because they enable us to join the world as it really is, not as our limited egos imagine it is.

Maybe learning a language will earn you more money or help strengthen national security. Maybe it’ll help stave off Alzheimer’s and dementia a little longer. Maybe it’ll help you succeed romantically (the narrator of the Beatles’ song “Michelle” would certainly have benefitted from knowing more French). Maybe it’ll help you appreciate other cultures. Maybe it’ll give you another facet to your identity as insurance against being subsumed by your job and finding yourself at retirement with no idea of what you actually enjoy. Various studies have validated all of these claims to one degree or another. It’s not guaranteed to do any of those things, though, and none of them need to be true for it to be worth it.

What it is guaranteed to do is take you out of your head and help you resist your own self-enclosing habits.

It is as logically incoherent to talk about “the end of foreign-language learning” because of declining college enrollments as it is to talk about “the end of love” because of an increase in the divorce rate. We should learn a foreign language – or pick up the violin, or find whatever activity gives us that “self-forgetful pleasure in the sheer alien pointless independent existence” of the world – because it makes us better people. And we shouldn’t be too quick to take up the offer of AI to relieve us of this important work. It is its own telos, as Murdoch would say, just like loving someone is.