by Richard Farr

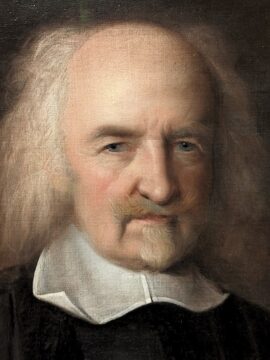

Historians often ask what led to Trump’s landslide victory back in 2024. All those guilty verdicts in the “PornHush” trial certainly helped — the final proof, for many, that the President was an innocent lamb set upon by crooks. And the November exit polls showed that millions of patriotic Americans found democracy a chore anyway, or were actively Fascism-curious, or simply got a buzz out of the fact that, being disempowered in every other meaningful way, they could at least step up and play a part in destroying their own children’s future. But surely the decisive factor was Trump’s inspired choice of running mate — philosopher and controversialist Thomas Hobbes.

Historians often ask what led to Trump’s landslide victory back in 2024. All those guilty verdicts in the “PornHush” trial certainly helped — the final proof, for many, that the President was an innocent lamb set upon by crooks. And the November exit polls showed that millions of patriotic Americans found democracy a chore anyway, or were actively Fascism-curious, or simply got a buzz out of the fact that, being disempowered in every other meaningful way, they could at least step up and play a part in destroying their own children’s future. But surely the decisive factor was Trump’s inspired choice of running mate — philosopher and controversialist Thomas Hobbes.

Sharp as a tack, a hard-bitten political realist, an intellectual heavyweight, and a precise, stylish communicator — he was so different from anyone else Trump could have chosen! The sore losers claimed he had not been born in the United States, or pointed out that he’d died in 1679. None of that mattered when the electorate saw what an ideal ticket it was.

Like the other VP aspirants, Hobbes described Trump as our only hope in dark times. In fact he iced that particular cake by calling him “our very Salvation, our Messiah, in whose Second Coming should we not earnestlie beleeve?” Like them, he also said that modern intellectual fads such as democracy, the separation of church and state, an independent judiciary, a free press and the rule of law were “monstrous and absurd Doctrines, manifest Phantasmes of Satan” and “beleeved in not, save by Idiots.” But he didn’t just say those things because it was the only way to land a lucrative government sinecure from which he he could denounce the evils of government, or because his highest aspiration was to visit Palazzo a Lago and rub shoulders with the shiftless rich. No — he said them because he could prove them.

His election-cycle bestseller Leviathan used rigor and logic to demonstrate two key political facts:

First, the ideal system of government — indeed the only system of government a rational agent will choose — is absolute monarchy. Argument in a nutshell: (i) it’s not just Trump who’s a vicious, self-interested brute — we all are; (ii) human nature being so dire, safety is more important than liberty; (iii) sorry but you can’t have both.

Perhaps even more striking than this was his second thesis. You might have the chance to choose your absolute ruler or you might not, he said. But either way, the right absolute ruler, the one whose boots you will find yourself grateful for the opportunity to lick, is precisely whoever is capable of becoming the absolute ruler. In Hobbes’s fanciful State of Nature, that could be the person with the biggest stick, but it’s more likely to be the person most cunning about other methods of acquiring power over others. And Trump, in a maneuver that would have looked original except that Hobbes foresaw it, acquired his power by taking one of the many inherently doomed systems of government — in this case an embarrassingly chaotic mess called representative democracy — and using its very instability as a ladder to be climbed and kicked away.

Hobbes was full of admiration for the way Trump grasped this idea — it was almost as if, per imposible, he had read the book. But he was also clear that once Donnie Darko (as he liked to call him) had been re-installed on the Golden Bidet of State, no one either should or should want to do anything about it. For to oppose the will of the “Soveraigne” (using his special technical jargon here) is to threaten “Civill Warre, and a return to Anarchy, or Democracy, which the difference I wot not.”

Leviathan offers a warning about this sovereign that the new VP notably did not repeat, but did not retract either, on taking office. It’s this. The person who comes to exercise absolute power over us might be virtuous and wise — though, given human nature as described, “wisdom recommendeth not witholding the Breath.” Then again, he might merely be self-interested in the ordinary way. But equally he might be (let’s imagine, for the sake of argument) a brutal, petty, vindictive, smug, cruel, unstable, illiterate, scheming, cowardly, vapid, needy, bullying, boorish, dangerous, vengeful creep — the kind of individual so irrational and so corrupt that he should never have been given the keys to a second-hand sock shop, much less a government with three million employees, a six trillion dollar annual budget, and 5,044 nuclear warheads. Such a ruler might act “in such Sorte as to ruin peradventure your entire Day.” Here’s the punchline: it makes no difference. Now that he holds the reins, all you have to do is look at the alternative — not a fear of chaos, but a guarantee of it. As Hobbes wrote in an early draft of his great book:

“Lacking Sovereigne Power — obeyed without Question, out of Terrour, and thus able to hold our worst Inclinations in check — there can be naught but Warre of All against All, with continuall Feare, and danger of violent Death, and the Life of Man lonely, impecunious, unpleasant, uncouth, and curtailed.”

Hobbes understood that living under a sovereign like this might be rough. But when he discovered that Trump himself was less interested in ruling than in eating, playing golf, and shouting at people, he made the most of it.

Cleverly, he opted not to abolish all the institutions that symbolize those quaint old Anglo-Saxon ideas about freedom, representation, and consent; the House and Senate for example remained especially useful as decoration. But journalists and political parties were declared unpatriotic, along with veggie burgers and the word climate. Open carry of the Trump Bible (containing now the recently discovered Book of Bannon, the Letter of Pompeo to the Militias, and the Book of Jared, also known as Evaluations) was made mandatory in public places. Taxation was abolished, except on the minimum wage. And, after one Supreme Court justice died in a most gruesome and unfortunate accident, the remaining eight held an emergency session, reversed Marbury v. Madison (“egregiously wrong” according to Justice Thorsuckalvarett) and declared that the Constitution was clearly only ever meant to be advisory anyway. (“In the last analysis — and this will be our last analysis — what counts as constitutional or even legal is a question solely at the discretion of Dear Leader.”)

On the back of these efforts and only a year into his term, new polls indicated that Ol’ Cinnamon Buns (as he was affectionately known by the common sort) had achieved a 117% approval rating — an almost unbelievable result! In honor of the achievement, Hobbes himself suggested the new title Donaldus I, Rex Americorum.

Ah, but there was a worm in the apple of this perfect tyranny. Millions had read their Leviathan, underlining the passages they were instructed to underline. But anonymous troublemakers started to call out more problematic aspects of the text.

Hobbes had written that it was irrational to accept anything less than total authoritarianism, because every other system was prey to decline and explosive dissolution. But transferring your liberty to the sovereign only made sense if you retained one “inalienable” right — the right to defend your person and your honor against the threat of their destruction even by the sovereign himself. Furthermore, it was the subject, not the sovereign, who must judge whether this Rubicon has been crossed. Did this not cause “a weaknesse” in the argument?

Different people cited different moments as their personal Rubicon. Some said it was the unhinged look on Trump’s face when he loudly cheered China’s invasion of Taiwan. Some could not quite swallow his privatization of the Marine Corps, or the sale of Yellowstone, Zion and Yosemite to mining interests. Others balked when they saw the red plastic button marked BANG! at Trump’s elbow during his announcement that he was gifting a nuclear bomber squadron to Brother Putin to counter the growing threat from Lithuania. Whatever it was, something made people wonder whether there was not, in these newly petrifying circumstances, a right to revolution. As one of them famously blogged:

“When in the course of human events it becomes necessary for a people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with their tyrant’s repeated injuries and usurpations, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should explain just what a monumental f****** disaster it has all been.”

Thus the wheel turned and the second war of independence began. Hobbes yet again fled to France. Groups of patriots yet again dressed up as “Indians,” this time stealing Trump’s Presidential limousine and driving it into Boston Harbor — hence the popular catch-phrase “no taxi without representation.” A group of extremists in Philadelphia, calling themselves The Framers, wrote a new constitution; like the old one, it was full of hopeful but infuriatingly vague language about rights that would later congeal into Holy Writ.

Yet again America found itself embroiled in the bloody chaos of revolution, fighting to recover its liberty from a half-wit king.

*