by Mike Bendzela

Over thirty years ago, my then-partner-now-spouse, Don, began planting heritage apple trees on the small farm where we are tenants, in an attempt to partially restore the historical orchard of Herbert W. Dow, traditional Maine farmer and cider-imbiber.

Herbert’s original, handwritten map of the apple trees he grew out back was still in a desk in the house when Don moved here in the 1970s; so, we have been able to research and replant some of the old varieties Herbert grew. We decided we would tend the trees “organically,” or something equivalent, because, you know, toxic chemicals and all that, and we would sell rare apples to local markets.

This organic ideal did not last long, however. Little did we know what nature had in store for us.

Swiss botanist Augustin Pyramus de Candolle, whose view profoundly influenced Charles Darwin, declared that “all nature is at war, one organism with another.”

The greater choke the smaller, the longest livers replace those which last for a shorter period, the more prolific gradually make themselves masters of the ground.

The belief that having “dominion” over nature exempts the husbandman from this Darwinian fray is romanticized claptrap. Raising any crop requires a farmer to tend simultaneously to the needs of a hospital and slaughterhouse. What follows is a compendium of just a few of the horrors baked into your apple pie.

*

Off with their heads

Most heritage apple varieties are biennial bearers, meaning they overproduce one year and then shut down from exhaustion the next. During an “on” year, I set about in June aborting most of the apples in our orchard. If I don’t, the apples will turn out small, limbs will break from overcropping, and the trees will relapse deeper into their biennial habits.

Once the petals have dropped and the bees have departed, I spray on carbaryl, an insecticide that simultaneously poisons a loathsome weevil and shocks the trees into shedding many of their apples. This method doesn’t work on all heritage varieties, though. So, a few weeks later, I have to climb a ladder to remove apples manually. One-by-one, I clip them from their clusters, leaving behind just the “king” fruit that develops from the central blossom of a five-blossom cluster. That means, during a good bloom year, far fewer than half of the fruit survives my depredations.

Once in a while I have to decapitate even the king, because it has a small, ugly scar that signals its doom. This is the bite mark of the loathsome weevil, which poaches baby apples to serve as makeshift uteri for its eggs and larvae.

For eons, the plum curculio (Conotrachelus nenuphar) settled for native plum trees; then, in the 17th century, European invaders introduced the Asian apple tree to this continent, which the curculios took a shine to, thereby creating the current Darwinian drama.

An organic farmer once said to me that pest species have as much a right to live as farmers do. Would that the pests returned such fine sentiment. But plum curculios kill their thousands–and the farmer his tens of thousands.

*

Extirpate the competition

Years ago, at a workshop in organic orcharding, it was explained to me that there were no organically approved “materials” (read “insecticides”) for round-headed apple borers (Saperda candida). These are beetles that lay their eggs in the trunks of young apple trees, just under the bark, where the larvae commence chewing the tree from the inside-out for years, until the trunk is so weakened it snaps off at the ground. I was advised to coat the trunks of my several dozen new trees with white paint, enclose them in window screen, crawl around on my hands and knees periodically looking for larval “frass” or feces oozing out through holes in the bark, clearly indicating that the trees are infested, and try to dig out the larvae with a piece of wire. But this wouldn’t prevent another beetle from laying a new egg the next day. Trees remain susceptible to this pest for about the first eight years of their lives, and new apple trees cost about fifty bucks apiece now.

I detest wielding a spray gun, but in a world where the “master of the ground” cannot opt out of Augustin Pyramus de Candolle’s war, even in his own sacred grove, these things must be done. And now I haven’t seen round-headed apple borers in years.

These pests aren’t new and, in fact, the pests that plague orchards in New England are mostly native ones. So, how did Herbert Dow manage it, a hundred years ago?

With arsenic. And lead. (Now illegal.)

Surely, organic orchards exist, so how do they do it? I once attended a talk at which a large fruit grower was only too glad to share how he plays the organic game. This farmer is a paradox, a “conventional” grower who grows organic apples as well. His orchard is so large, our entire year’s take is but a daily rounding error to him. His talk was a hoot.

In the midst of his “conventional” orchard, this farmer has designated a plot of several thousand trees as “organic.” He sprays the conventional Macintosh trees on the perimeter of the organic plot with synthetic materials as usual, twelve or so times per year, with tank mixes of insecticides, and fungicides, and miticides, and antibiotics, and thinners, and nutrients, and growth regulators–all perfectly legal, all perfectly low-risk when practiced legally. Inside the organic “buffer,” he sprays only “certified” and “natural” materials–which this farmer summarized as “sulfur, sulfur, and more sulfur,” to deal with apple scab fungus. For insects, he applies less-effective “botanical” insecticides and silicate clays by the ton–and he sprays them often. He sprays, like, twenty-two times per year!

So, there you have it: Large-scale mechanization to move tons of sulfur and clay into the orchard; voluminous sales at mark-ups sometimes well over 100 percent; and a free adversarial marketing campaign supplied by the Organic Consumers Association, the Environmental Working Group, and Whole Foods Market. A real winner. For me, twenty-two times donning the raincoat, face shield and gloves in my little plot–two hours of spray time, on foot, multiplied twenty-two times–ain’t gonna happen. We are, by simple default, a “low-spray” orchard.

Yet, no matter the methods we choose, nature continues in its implacable, indifferent ways.

*

Fruit flies like an apple

When I’m not exterminating pests, I’m mulling over them, because some of them are actually quite interesting. For example, long before human occupation of North America, there lived a little fruit fly in wild hawthorn trees called Rhagoletis pomonella. For countless millennia, these flies emerged in mid-summer to hang out on hawthorn fruits where they courted and mated, laying their little eggs in the fruits themselves, which are only about the size of cherries. The Rhagoletis maggot babies dined on the interior flesh of the little hawthorn fruits until they died and fell off the tree. The maggots would then crawl out of the fruit and into the ground to pupate and start the cycle over.

Then one day in the mid-1800s, some hawthorn flies were on their little piece of real estate, mating away, when they happened to glance over and see, in the next tree over, a fruit of pornographic size, Malus–an apple. The Rhagoletis flies moved in on this apple–an alien introduced by aliens–and they never looked back. Eve was never so transfixed by a piece of fruit.

A coterie of Rhagoletis now lays eggs only in apples, and their maggots turn the insides of our luscious fruit to shit, literally. They won’t have anything to do with hawthorns anymore and have been rechristened “Apple Maggot Flies.” (Wondrously, their wing patterns imitate jumping spiders, to frighten off predators!)

This has been hailed as a “sympatric speciation event,” and the discoverer of the new species in genus Rhagoletis, Benjamin Walsh, even wrote to Charles Darwin about it; so now you can read in The Origin of Species,

Mr. B. D. Walsh, a distinguished entomologist of the United States, has described what he calls Phytophagic [plant-feeding] varieties and Phytophagic species. Most vegetable feeding insects live on one kind of plant. . . . In several cases, however, insects found living on different plants have been observed by Mr. Walsh . . . to differ in a slight degree. When the differences are strongly marked . . . the forms are ranked by all entomologists as good [recognizable] species.

In short: some little flies have evolved outright in real time, just to take advantage of our advances and destroy our livelihoods. Is it any wonder that farming turns us into such murderers?

*

2021, plague year

One might think that after so many years of dealing with pests, we have seen it all and are prepared each year for nature’s onslaught. One would be wrong. Call it “Adam’s Bedevilment.”

Darwin’s friend and mentor, geologist Charles Lyell, described pest management as being like “staying the course of a burning stream of lava.” We had experienced mammalian pests (deer, voles and porcupines), insects (weevils, flies, moths and beetles), mites, and fungi. But next on tap was something we were not accustomed to in cold Maine–a bacterium, Erwinia amylovora, popularly known as fire blight–which a warming climate has served our way.

Thus, 2021 proved to be a crash course in Pathogenesis 101. From sweating behind surgical masks in supermarket lines, to worrying about my brothers sick with covid-19 (they recovered fine), to chopping apart my beloved Newtown Pippin tree to arrest the depredations of Erwinia amylovora, I did not spend a single day without thinking at least once about infection, vectors, symptoms, signs, and prophylaxis.

According to the University of Maine Extension, 2021 was probably “the worst fire blight year for noncommercial apple plantings in Maine history.” We entered 2021 with a high probability of Erwinia inoculum in the orchard, so, in mid-April, I made sure to spray a mix of copper sulfate and oil on all the trees before the leaves had extended beyond one-quarter-inch green. I had to be careful as copper is toxic to plants as well as bacteria. The copper turned out to be a waste.

May was magnificent—until it wasn’t. Sunny, warm weather ushered in our best bloom since 2015, but too early. Then, it just stopped raining, and the heat became relentless.

Bloom came and went, I sprayed the insecticide and fungicide I usually spray at this time, and things quickly went south. I cannot hope to spray the antibiotic streptomycin during bloom as commercial orchards do because there is no way to get proper spray coverage with just a spray wand hooked to a thirty-gallon tank.

By the end of the first week in June, I was cutting blight strikes out of mature trees. Shoots, fruit, and whole limbs were wilting and blackening. For June and July, and most of August, I was focused only on pruning out blight, neglecting my hand-thinning, with strikes showing up daily. I began to worry I was butchering the trees.

An immature apple oozing orange droplets is a nauseating sight. A single droplet of ooze contains enough inoculum to infect an entire acre of trees. A friend who is a retired molecular biologist said that one droplet probably contains on the order of ten-to-the-ninth bacteria. The hideous irony of Erwinia is that the primary vector is the beloved honeybee, which is attracted to the ooze. Bees become contaminated with bacteria and spread it throughout the orchard, flower by flower, until the entire planting is doomed.

Somehow, all but one of the immature trees escaped infection (Pewaukee, RIP), but almost all the old trees suffered strikes, some worse than others. Four trees would probably have to be cut down in the winter.

Through August, I continued to cut necrotic branches out of my favorite trees, such as Newtown Pippin, my premiere cider apple and loaded with fruit last year. As with cancer, you cut and cut and hope you get it all.

In the end, we survived our bout with fire blight. This year has brought a reprieve from the butchering, with (temporarily) cooler summer weather.

*

Farming apes

This describes some of our experiences and activities on a single acre, with eighty apple trees and several peach and plum varieties. Now, extrapolate this over a hundred million acres of multitudinous, distinctive crops and imagine the struggle involved in keeping our supermarkets stocked. As species vanish and the climate deteriorates, I wonder if it all hasn’t been a gargantuan mistake, but there is no turning back now.

In any case, everyone, especially the picky, self-righteous consumer, needs to understand this: Farmers kill. We abort and impede and poison a thousand thousand entities for every entity we tend; for if we don’t, nature will continue on in its blind, murderous ways. These necessary deaths are “checks,” in Darwin’s sense of the word:

[W]e may confidently assert, that all plants and animals are tending to increase at a geometrical ratio, that all would most rapidly stock every station in which they could any how exist, and that the geometrical tendency to increase must be checked by destruction at some period of life.

Darwin’s insight is worth repeating: The geometrical tendency to increase must be checked by destruction.

That is the horrifying reality of Life on Earth, but somehow, through our technologies, farming and otherwise, we have become a singular species, one that has managed (thus far) to dodge this iron law. And so, whilst our numbers have grown from 1.8 billion in Herbert Dow’s time to 7.8 billion in our own time, CO2 levels have risen from about 300 parts per million to 420 ppm. The earth has become one big hot house and ape farm. If our little experiment growing heritage apples at Dow Farm is any indication, this great ape’s future persistence means war without end.

Thanks to my husband, Don Essman, and the owners of Dow Farm, Ken Faulstich and Claudia White, for bearing this struggle with me.

________________________________

Portions of the description of hand thinning are excerpted from the essay, “For the Love of Apples,” published in Stonecoast Review Literary Arts Journal, Summer 2017. The section on fire blight is based on a piece submitted to the Maine Fruit Tree Newsletter, Monday, August 9, 2021.

Images

Photograph of Herbert W. Dow from the estate of Dow Farm.

“Rhagoletis pomonella – Apple Maggot Fly” by woolcarderbee is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

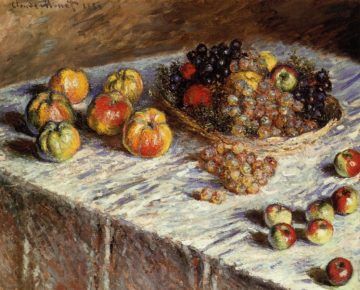

Claude Monet’s “Still Life with Apples and Grapes,” 1879. WikiArt.

Photograph of Cumberland Fair apples taken by Jenn Grant.

All other photographs by the author.