by Jochen Szangolies

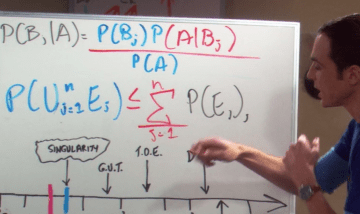

Thomas Bayes and Rational Belief

When we are presented with two alternatives, but are uncertain which to choose, a common way to break the deadlock is to throw a coin. That is, we leave the outcome open to chance: we trust that, if the coin is fair, it will not prefer either alternative—thereby itself mirroring our own indecision—yet yield a definite outcome.

This works, essentially, because we trust that a fair coin will show heads as often as it will show tails—more precisely, over sufficiently many trials, the frequency of heads (or tails) will approach 1/2. In this case, this is what’s meant by saying that the coin has a 50% probability of coming up heads.

But probabilities aren’t always that clear cut. For example, what does it mean to say that there’s a 50% chance of rain tomorrow? There is only one tomorrow, so we can’t really mean that over sufficiently many tomorrows, there will be an even ratio of rain/no rain. Moreover, sometimes we will hear—or indeed say—things like ‘I’m 90% certain that Neil Armstrong was the first man on the Moon’.

In such cases, it is more appropriate to think of the quoted probabilities as being something like a degree of belief, rather than related to some kind of ratio of occurrences. That is, probability in such a case quantifies belief in a given hypothesis—with 1 and 0 being the edge cases where we’re completely convinced that it is true or false, respectively.

Beliefs, however, unlike frequencies, are subject to change: the coin will come up heads half the time tomorrow just as well as today, while if I believe that Louis Armstrong was the first man on the moon, and learn that he was, in fact, a famous Jazz musician, I will change my beliefs accordingly (provided I act rationally).

The question of how one should adapt—update, in the most common parlance—one’s beliefs given new data is addressed in the most famous legacy of the Reverend Thomas Bayes, an 18th century Presbyterian minister. As a Nonconformist, dissent and doubt were perhaps baked into Bayes’ background; a student of logic as well as theology, he wrote defenses of both God’s benevolence and Isaac Newton’s formulation of calculus. His most lasting contribution, however, would be a theorem that gives a precisely quantifiable means of how evidence should influence our beliefs. Read more »

The coronavirus pandemic has caused a great of suffering and has disrupted millions of lives. Few people welcome this kind of disruption; but as many have already observed, it can be the occasion for reflection, particularly on aspects of our lives that are called into question, appear in a new light, or that we were taking for granted but whose absence now makes us realize were very precious. For many people, work, which is so central to their lives, is one of the things that has been especially disrupted. The pandemic has affected how they do their job, how they experience it, or whether they even still have a job at all. For those who are working from home rather than commuting to a workplace shared with co-workers, the new situation is likely to bring a new awareness of the relation between work and time. So let us reflect on this.

The coronavirus pandemic has caused a great of suffering and has disrupted millions of lives. Few people welcome this kind of disruption; but as many have already observed, it can be the occasion for reflection, particularly on aspects of our lives that are called into question, appear in a new light, or that we were taking for granted but whose absence now makes us realize were very precious. For many people, work, which is so central to their lives, is one of the things that has been especially disrupted. The pandemic has affected how they do their job, how they experience it, or whether they even still have a job at all. For those who are working from home rather than commuting to a workplace shared with co-workers, the new situation is likely to bring a new awareness of the relation between work and time. So let us reflect on this.

I often hear it said that, despite all the stories about family and cultural traditions, winemaking ideologies, and paeans to terroir, what matters is what’s in the glass. If a wine has flavor it’s good. Nothing else matters. And, of course, the whole idea of wine scores reflects the idea that there is single scale of deliciousness that defines wine quality.

I often hear it said that, despite all the stories about family and cultural traditions, winemaking ideologies, and paeans to terroir, what matters is what’s in the glass. If a wine has flavor it’s good. Nothing else matters. And, of course, the whole idea of wine scores reflects the idea that there is single scale of deliciousness that defines wine quality. Finally, outrage. Intense, violent, peaceful, burning, painful, heart-wrenching, passionate, empowering, joyful, loving outrage. Finally. We have, for decades, lived with the violence of erasure, silencing, the carceral state, economic pain, hunger, poverty, marginalization, humiliation, colonization, juridical racism, and sexual objectification. Our outrage is collective, multi-ethnic, cross-gendered and includes people from across the economic spectrum. One match does not start a firestorm unless what it touches is primed to burn. But unlike other moments of outrage that have briefly erupted over the years in the face of death and injustice, there seems to be something different this time; our outrage burns with a kind of love not seen or felt since Selma and Stonewall. Every scream against white supremacy, each interlocked arm that refuses to yield, every step we take along roads paved in blood and sweat, each drop of milk poured over eyes burning from pepper spray, every fist raised in solidarity, each time we are afraid but keep fighting is a sign that radical love has returned with a vengeance.

Finally, outrage. Intense, violent, peaceful, burning, painful, heart-wrenching, passionate, empowering, joyful, loving outrage. Finally. We have, for decades, lived with the violence of erasure, silencing, the carceral state, economic pain, hunger, poverty, marginalization, humiliation, colonization, juridical racism, and sexual objectification. Our outrage is collective, multi-ethnic, cross-gendered and includes people from across the economic spectrum. One match does not start a firestorm unless what it touches is primed to burn. But unlike other moments of outrage that have briefly erupted over the years in the face of death and injustice, there seems to be something different this time; our outrage burns with a kind of love not seen or felt since Selma and Stonewall. Every scream against white supremacy, each interlocked arm that refuses to yield, every step we take along roads paved in blood and sweat, each drop of milk poured over eyes burning from pepper spray, every fist raised in solidarity, each time we are afraid but keep fighting is a sign that radical love has returned with a vengeance.

During the 1990s, the impossibility of a black president was so ingrained in American culture that some people, including many African Americans, jokingly referred to President Bill Clinton as the first “black president.” The threshold Clinton had passed to achieve this honorary moniker? He seemed comfortable around black people. That’s all it took.

During the 1990s, the impossibility of a black president was so ingrained in American culture that some people, including many African Americans, jokingly referred to President Bill Clinton as the first “black president.” The threshold Clinton had passed to achieve this honorary moniker? He seemed comfortable around black people. That’s all it took.