by Emrys Westacott

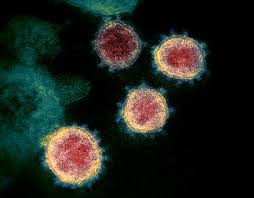

Numerous reports have been compiled and articles written about the way that the covid pandemic has affected, or will affect, work: the way people do it, and their attitude towards it. But although certain general trends can be identified–e.g. the percentage of meetings held online rather than face-to-face has, naturally enough increased–people’s attitudes towards work and the workplace haven’t been affected in a uniform way.

Many of those who have been able to work more from home relish the advantages of doing so. They avoid time-consuming and often stressful commutes; they are able to integrate the business of ordinary living–going to the dentist, picking up a prescription, working when the kids are off school, etc.–with getting their work done. Hours can be more flexible, and the same goes for the dress code.

For others, though, working from home all the time has many drawbacks. Commuting may have a bad reputation, but for a surprising number of people it can be positively enjoyable. A Canadian study found that where the commute take less than 30 minutes more than 50% of respondents said that they enjoy their commute. And among people who cycle to work, almost a fifth said that the commute was the best part of their day.[1]

The flexibility and freedom that working from home allows is undeniably a plus. But for some, the stricter routine provided by a requirement to show up at the workplace by a certain time brings order to the day and to the use of one’s time.

Most of all, though, physical workplaces serve an important social function. Just as it is good for our physical and mental health to to get outside every day and to be in regular touch with the natural world, so it is beneficial for most of us to meet and interact with other people regularly. The relationships in question may not be the most important ones in our lives: those with our fellow workers often are not. The conversations we have don’t have to be especially intimate or stimulating. But they can still be meaningful: occasions for sorting out a problem, cracking a joke, complaining about something or someone, giving or taking advice, offering or receiving a compliment. Read more »

A friend, knowing that I’ve been learning German, recently sent me a volume of Theodore Fontane’s poetry. Fontane (1819-1898) is best known today for the novels that he wrote in the later part of his life. But some his poems have an affecting simplicity–a simplicity that is perhaps especially charming to those of us who are less than fluent in German. Here is one lyric that particularly caught my attention. It expresses a sentiment that seems most suitable to the present time as we approach the end of a bleak winter and, one hopes, of a devastating pandemic. Naturally, the translation takes some liberties in an attempt to retain something of the feel and spirit of the original.

A friend, knowing that I’ve been learning German, recently sent me a volume of Theodore Fontane’s poetry. Fontane (1819-1898) is best known today for the novels that he wrote in the later part of his life. But some his poems have an affecting simplicity–a simplicity that is perhaps especially charming to those of us who are less than fluent in German. Here is one lyric that particularly caught my attention. It expresses a sentiment that seems most suitable to the present time as we approach the end of a bleak winter and, one hopes, of a devastating pandemic. Naturally, the translation takes some liberties in an attempt to retain something of the feel and spirit of the original. The coronavirus pandemic has caused a great of suffering and has disrupted millions of lives. Few people welcome this kind of disruption; but as many have already observed, it can be the occasion for reflection, particularly on aspects of our lives that are called into question, appear in a new light, or that we were taking for granted but whose absence now makes us realize were very precious. For many people, work, which is so central to their lives, is one of the things that has been especially disrupted. The pandemic has affected how they do their job, how they experience it, or whether they even still have a job at all. For those who are working from home rather than commuting to a workplace shared with co-workers, the new situation is likely to bring a new awareness of the relation between work and time. So let us reflect on this.

The coronavirus pandemic has caused a great of suffering and has disrupted millions of lives. Few people welcome this kind of disruption; but as many have already observed, it can be the occasion for reflection, particularly on aspects of our lives that are called into question, appear in a new light, or that we were taking for granted but whose absence now makes us realize were very precious. For many people, work, which is so central to their lives, is one of the things that has been especially disrupted. The pandemic has affected how they do their job, how they experience it, or whether they even still have a job at all. For those who are working from home rather than commuting to a workplace shared with co-workers, the new situation is likely to bring a new awareness of the relation between work and time. So let us reflect on this. When I feel myself becoming irritable, disheartened, or just plain fed-up with life during the pandemic, I find it helpful to conduct a thought-experiment familiar to the ancient Stoics. I reflect on how much I have to be grateful for, and how things could be so much worse. That prompts the more general question: Who are the fortunate, and who are the unfortunate at this time?

When I feel myself becoming irritable, disheartened, or just plain fed-up with life during the pandemic, I find it helpful to conduct a thought-experiment familiar to the ancient Stoics. I reflect on how much I have to be grateful for, and how things could be so much worse. That prompts the more general question: Who are the fortunate, and who are the unfortunate at this time?

The current Covid 19 pandemic is undoubtedly a disaster for millions of people: for those who die, who grieve for the dead, who suffer through a traumatic illness, or who, suddenly lacking work and income, face the prospect of dire poverty as the inevitable recession kicks in. And there are other bad consequences that one might not describe as ‘disastrous” but which are certainly significant: the stress experienced by all those providing care for the sick; the interruption in the education of students; the strain put on families holed up together perhaps for months on end; the loneliness suffered by those who are truly isolated; and the blighted career prospects of new graduates in both the public and the private sectors.

The current Covid 19 pandemic is undoubtedly a disaster for millions of people: for those who die, who grieve for the dead, who suffer through a traumatic illness, or who, suddenly lacking work and income, face the prospect of dire poverty as the inevitable recession kicks in. And there are other bad consequences that one might not describe as ‘disastrous” but which are certainly significant: the stress experienced by all those providing care for the sick; the interruption in the education of students; the strain put on families holed up together perhaps for months on end; the loneliness suffered by those who are truly isolated; and the blighted career prospects of new graduates in both the public and the private sectors.