by Rafaël Newman

On the first day of August in Year One AC (anno coronae), I boarded an Intercity train in Zurich bound for Singen, in the German federal state of Baden-Württemberg. In Singen I transferred to the Intercity headed to Stuttgart but left the train a few stops shy of the state capital, at the town of Horb am Neckar, where I was met by friends and driven to Burg Hohenzollern. Looming over the mild and hilly Swabian countryside, the castle is the ancestral seat of the senior branch of the dynasty that would go on to rule Prussia, and eventually the German Empire, before retiring to wealthy obscurity at the end of World War One.

What was noteworthy about my first excursion across the Swiss border in over six months, since a winter holiday spent in Alto Adige before the lockdown, was not so much its particular destination (although that will bear mention below) as its timing: August 1, or Erschtouguscht in Swiss-German dialect, is the annual commemoration of Switzerland’s founding, and thus, depending on your political coloration, either a uniquely unpatriotic day to leave the country, or the ideal moment for an escape from the pathos and pyrotechnics of a populist rite.

European national holidays are typically history-laden affairs, at least in their original conception. Of the countries just beyond Switzerland’s borders, France hosts the most venerable festivities. The Quatorze Juillet marks the significant initial, if not particularly effective, revolutionary gestures of July 1789, and lends the symbolic elements of its exercise – stormed ramparts, tricolore, battle hymn – mutatis mutandis to the general vocabulary of national identity. Italy’s is the next eldest, although it celebrates a political event fully two centuries later: the Festa della Repubblica, on June 2, commemorates the referendum in 1946 in which the Italian electorate opted for a republican form of government following the fall of fascism, and features wreath-laying and a military parade.

Austria’s national day, the Neutralitätserklärung on October 26, is younger still, and recalls the constitutional law on permanent neutrality ratified by the Austrian parliament in 1955 with a wreath-laying ceremony and a rather more discreet display of military capability. Germany, finally, has the newest national day of all of Switzerland’s neighbors, having opted in 1990 to celebrate its newly won unity (and not, importantly, its re-unification) with a Tag der deutschen Einheit on the otherwise anodyne date of October 3, rather than on November 9, the day on which the Berlin Wall in fact fell, but which is inconveniently also cathected by the Reichspogromnacht of 1938, otherwise known as Kristallnacht.

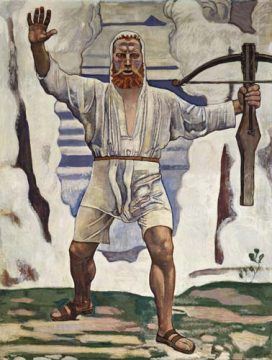

On its national day, in distinction to its neighbors, with each of which it shares a national language, Switzerland celebrates not a foundational event in the immediate past, in the modern or even early modern period, but a medieval episode – the Rütlischwur, or Oath of the Confederates, in 1291 – so remote it has accreted semi-legendary features, such as the emblematic figure of Wilhelm Tell: as if Switzerland wished to insist on its righteous seniority and homogeneous autochthony in the face of the larger, grander nation states surrounding it, each with a more renowned martial or cultural profile, and to remind the world of the continuity of its territorial integrity on a continent otherwise riven by war and destruction. Furthermore, Switzerland frames its founding as a gesture of ethnic independence from external subjugation, rather than as an act of internal, structural self-determination: less of a revolution against an oppressive class, as in France, than a liberation from an occupying foreign power (as in the case of Austria “liberated” from the Germans after the defeat of the Nazis: although of course in Swiss historiography “Austria” itself, or rather its precursor, the House of Habsburg, plays the part of the foreign power).

Thus Switzerland’s national day is an outlier in Europe: an ancient saga and the expression of an unfashionable faith in unbroken ethnic lineage. In fact, though, Switzerland’s celebration is of relatively recent vintage, having been proposed as a federal holiday only in the late 19th century in conjunction with festivities marking the birthday of the capital city of Bern and not made official until the late 20th century. Its instatement as a commemoration of Switzerland’s putatively immemorial beginnings does nevertheless have ideological roots in a slightly earlier period: namely the era of romantic ethnography during the Biedermeier period in the first half of the 19th century, when the rural Christian reformer and novelist Jeremias Gotthelf, a controversial pioneer of the use of local dialect in his “high German” writing, followed such German champions of national identity as the Grimm brothers (who had included the story of Wilhelm Tell in their collection of German sagas) in warning that “it is high time to collect the [Swiss] sagas, since the present is so consuming that people are forgetful of the past.” Thus it was precisely the rapid pace of modernization in Europe and beyond, felt even in the idyllic Swiss countryside, that called for a countercurrent of memory of a glorious – or glorified – pre-modern past.

Switzerland today could, however, if it wanted to, celebrate a more contemporary, more palpably political episode, one with greater relevance to its present-day constitution and more in line with the commemorations surrounding it. In an essay originally published in 1967 but cited to this day by the reform-minded, Peter Bichsel, a writer and sometime member of the Swiss Social Democratic Party, noted that it would make more sense to mark the anniversary of Switzerland’s modern (re-)emergence, in September of 1848, following the unrest of the Napoleonic wars, the rise of constitutional movements across Europe, and an abortive civil war at home, when the country accorded itself the political form it enjoys to this day: “Our country is 120, perhaps 150 years old,” Bichsel wrote, allowing Switzerland early modern origins stretching back at most to the Congress of Vienna. “Everything else is prehistory and has much to do with our national borders and little to do with our land.” Nevertheless, Bichsel resigned himself, on the eve of the 120th birthday of the Swiss federal constitution, to the fact that his compatriots would likely always prefer the “brute swagger” (“Kraftprotzentum”) of the ancestral pageant on August 1 to a dry account of mid-19th-century statesmanship and parliamentary nation-building.

But surely the latter account, one of institutional compromise and regional, linguistic, and confessional equilibrium, of the triumph of liberalism over radicalism, should appeal to the rational Swiss, who share with their neighbors to the north an occasionally pedantic commitment to accuracy. Surely it should lead them to abandon the heroes of a mostly undocumented saga for the thoroughly documented architects of their beloved direct democracy. The Swiss, after all, are given to a drily ironic skepticism in the face of pomposity and exaggeration; furthermore, their devotion to their house pets has them annually sequestering dogs and cats in soundproof chambers, to spare them the trauma of the ubiquitous fireworks that accompany the rowdy annual celebration of a native uprising against foreign overlords. Wouldn’t they in fact prefer a more bureaucratic, less hoydenish birthday?

There is of course a deeper purpose served by the narrative underpinning the Swiss national day. In Sapiens, his account of the rise to sole power of our particular human “species”, the historian Yuval Harari accords pivotal importance to the function of storytelling in human culture: or rather, he explains our ability to organize our fellow humans beyond their immediate family or clan affiliations by means of the (symbolic) creation of imaginary entities, which then command belief and respect and serve to galvanize common action. Among the entities he identifies are religions, monetary systems, and corporations; from which it is a short step, guided by Benedict Anderson, to the nation. (And to the calendar, by the way, just as much a unifying, if arbitrary, cultural institution: as witness BC, AD … or AC.)

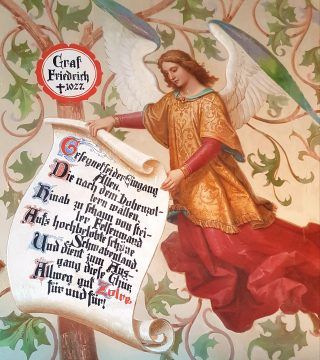

And thus it turns out that my extramural destination on August 1 was as significant as its timing: for Burg Hohenzollern in Swabia, present-day Baden-Württemberg, is nothing other than a gigantic stone narrative, an eclectic, historicizing pile designed to maintain, by means of ancestral portrait galleries and room-filling, heraldic family trees, the fiction of an elite dynasty in a country (Prussia) once coterminous with it but which has since entirely ceased to exist, having been subsumed into a fusion of the Germanic polities which has acquired, over the course of many decades, the appellation “Federal Republic of Germany”. Switzerland, all the more “multi-ethnic” in its composition, may thus be in need of a particularly good “story” to organize itself federally, beyond the ties of its citizens’ individual communitarian loyalties to thousands of municipalities, and across its multiple linguistic, religious, and regional boundaries.

And thus it turns out that my extramural destination on August 1 was as significant as its timing: for Burg Hohenzollern in Swabia, present-day Baden-Württemberg, is nothing other than a gigantic stone narrative, an eclectic, historicizing pile designed to maintain, by means of ancestral portrait galleries and room-filling, heraldic family trees, the fiction of an elite dynasty in a country (Prussia) once coterminous with it but which has since entirely ceased to exist, having been subsumed into a fusion of the Germanic polities which has acquired, over the course of many decades, the appellation “Federal Republic of Germany”. Switzerland, all the more “multi-ethnic” in its composition, may thus be in need of a particularly good “story” to organize itself federally, beyond the ties of its citizens’ individual communitarian loyalties to thousands of municipalities, and across its multiple linguistic, religious, and regional boundaries.

The question is, does the story told by the Swiss on August 1 this year still suit their purposes, and their present reality? The country today has grown beyond its “original” confederated Alemannic tribes and Romance acquisitions – and its male-only suffrage, preserved until as late as 1990 in one tiny holdout half-canton – to include a high proportion of “foreigners”, naturalized or not, whether Gastarbeiter (seasonal workers) who have stayed on past their initial contracts, their children, known as “Secondos” and “Secondas”, or a broad range of new arrivals; whether genteelly euphemistic “expats” or members of the more indelible minority groups, for whom there is an ominous-sounding, if well-meant new coining: people with Migrationshintergrund, or a “migratory background”. INES: Institut Neue Schweiz is a newly established “Think & Act Tank with Migrationsvordergrund” (the last word is a play on the neologism, foregrounding and “celebrating” migration rather than relegating it to the background). Founded in 2016, INES aims to portray a more realistic picture of Switzerland by assembling and disseminating “voices, faces, stories, images and realities from the migratory underground (Migrationsuntergrund)”. INES brings together a wide range of thinkers and activists, among them the writer and performance artist Jurczok 1001, who has described the mission facing progressive Swiss as “a matter of representing diversity and its development in Switzerland. To find other narratives for Switzerland that more accurately represent [its] reality. There is no such thing as the Switzerland as it is represented in its founding myth—we need to tell the story of another kind of Switzerland as it has existed now for a long time.” In his literary work, Jurczok plays an active role in this refurbishment of the “national” narrative, producing and performing texts that meld local dialect, a distant legacy of Gotthelf’s reformist realism, with a postmodern sensibility shaped by Black culture and German concrete poetry. That “other kind of Switzerland” includes women, first and foremost, elided in the Rütlischwur narrative and sidelined in the legend of Wilhelm Tell but variously present in the historical record, beginning with the defense of Zurich by its womenfolk against an invasion in 1292: foundational work, at least for the early modern history of women in Switzerland, has been done by the independent scholar Elisabeth Joris, among others. It includes ever more people of color, from all echelons of Helvetian power, among them the hallowed halls of the banks, bastion of Swiss privilege: see for example the work of Franziska Schutzbach. It must come to terms with the country’s involvement in the colonialist project, from which the its capitalists have extracted profit at least until the end of apartheid: see the work of Patricia Purtschert. And it should face up to the realities of its policy on refugees, which has become increasingly stringent in recent years in the face of the ongoing humanitarian disaster of forced migration: on which see, among others, Caroline Wiedmer, who traces a chilling genealogy linking repression of Zurich’s open drug scene in the 1990s with current legislation governing asylum seekers.

*

There is a street named after Wilhelm Tell in Zurich. Barely three blocks long, it intersects a short Strasse named for Ulrich Zwingli, the local protestant reformer. Both streets are to be found in the neighborhood of Aussersihl, known to older residents as Chreis Cheib or “Dead Horse Town”, since the area had once featured the disposal grounds for animal cadavers; it now includes the city’s traditional red-light district. Anglophone wags have suggested that Tell-Strasse should be rechristened “Don’t-Tell-Strasse”, in view of the discretion implicitly urged upon passersby amid contact bars and purveyors of controlled substances. In today’s culture of personal disclosure, however, in which memoir writers threaten to outnumber memoir readers, even among the normally buttoned-up Swiss, such an injunction is unlikely to be heeded. Nor should it be: for what the country needs these days is a thorough retelling, as a propaedeutic to the corresponding remaking.

There is a street named after Wilhelm Tell in Zurich. Barely three blocks long, it intersects a short Strasse named for Ulrich Zwingli, the local protestant reformer. Both streets are to be found in the neighborhood of Aussersihl, known to older residents as Chreis Cheib or “Dead Horse Town”, since the area had once featured the disposal grounds for animal cadavers; it now includes the city’s traditional red-light district. Anglophone wags have suggested that Tell-Strasse should be rechristened “Don’t-Tell-Strasse”, in view of the discretion implicitly urged upon passersby amid contact bars and purveyors of controlled substances. In today’s culture of personal disclosure, however, in which memoir writers threaten to outnumber memoir readers, even among the normally buttoned-up Swiss, such an injunction is unlikely to be heeded. Nor should it be: for what the country needs these days is a thorough retelling, as a propaedeutic to the corresponding remaking.