by R. Passov

In early 1970, after three years of fighting induction into the army, Muhammad Ali neared the end of his resources. In that same year, before he left for prison, my father gave me boxing lessons. I wasn’t going to be the type of fighter Ali was. According to my father, instead of back-peddling on my toes I needed to fight on the inside.

Between lessons I listened to stories about Jack Dempsey perfecting the weave, ducking under a jab, twisting all of his weight into a short left. Then about my father’s favorite, Rocky Marciano, who paid two punches to throw one and hit so hard it was worth it.

Rocky was from my father’s youth, when tough Irish, Italian and Jewish kids ran the black and white streets of eastern cities. An inside-the-game fighter, Rocky spoke straight at the camera in slow, perfect sentences, as if on the twenty-third take of his own thoughts. He didn’t threaten the limits of my father’s understanding. Instead, he was a man among his kind of men.

Ali was different; Black, lecturing, out of bounds, on his own, making change. I wanted from Ali what my father wanted from Rocky.

____________________________________________________

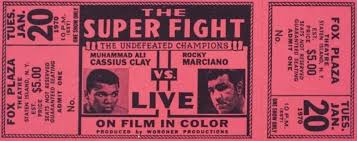

On January 20, 1970 a showman managed to con the public into paying more than my young mind could imagine to sit in theaters and watch ‘close circuit TV’ deliver a computer-generated matchup between Marciano and Ali.

Murry Woroner, then a 36-year-old radio huckster had already staged a series of elimination matches, pitting dead champions against the living; a boxing fantasy league before there were fantasy leagues.

A fantasy league purportedly made possible by that new wonder, the computer, the same machine that helped the Apollo Spacecrafts find the moon.

Murry recruited 250 experts, including the Dundee brothers – Angelo, Ali’s out of work trainer and Chris who would referee the Super Fight – to fill out a 58-page questionnaire. Boxers across the ages were ranked against the obvious attributes: Speed, power, stamina, footwork, training habits, but also the intangibles – grit, courage, the ability to take punishment, the will to win. Somehow, all of this filtered through “statistical reduction” and “stepwise regression” inside a “second generation NCR-315 packed with 5k of handmade core memory…”

Out came a series of fights narrated by Guy LeBow, the most recognized voice in boxing. Two stacks of matches were pre-arranged, with the ultimate showdown to be between the victor of each column. Beginning mid-way through 1968, the staged fights were carried on radio, according to Woroner, “…the real medium of imagination…”

In one stack, Marciano works through a list of past champions, mostly wining by late round knockouts, but more than once the “…computer…” orchestrates a match that goes the distance. Still, Marciano always wins.

In the other stack, fighters crawl over each other. In his first match, Ali knocks out Max Bear. In his second match, while The Great White Hope runs on Broadway, the computer has Ali lose to James J. Jeffries, the real “Great White Hope.”

____________________________________________________

After running around the globe for two years, on December 26th, 1908 in Sydney, Australia, Jack Johnson, then the Colored Heavyweight Champion, finally caught Tommy Burns, thereby becoming the first black man to hold the White Heavyweight Title.

In victory Johnson lived large, marrying three white women in succession, escorting countless others to his hotel rooms. It was too much even for Booker T. Washington who is purported to have said of Johnson, “…it is unfortunate that a man with money should use it in a way to injure his own people …”

Whether Woroner’s staging of Ali against Jeffries was genius or luck remains undiscovered. But for Ali it was clear. He sued Woroner for $1 million claiming to have been slandered by the mere thought that he could lose to “… history’s clumsiest, slow-footed heavyweight.”

Jeffries was far from slow footed. At his prime he was a fierce specimen whose training regimen, including daily runs of 14 miles, followed by countless sit-ups, pushups and sparring, would exhaust today’s heavyweights.

When Jeffries retired, 22 and 0, as Champion, bear-knuckle fighting was still fresh. Matches could last upwards of 50 rounds. The next fighter to retire undefeated, Marciano, was also a white champion.

And so it made sense that Jeffries was offered a purse of unheard of size to seize the title from the incorrigible Johnson. Choosing not to use the excuse of the purse, Jeffries defended his come-back by offering, “I came out of retirement for the sole purpose of proving that a white man is better than a negro.”

The promoters struggled to agree on a referee, at one point appealing to former President William Howard Taft then Arthur Cannon Doyle. A referee was finally secured for a match held in a bespoke arena in Reno Nevada. On July 4th, 1910, the temperature reached 110 degrees. At 3:00 in the afternoon, the fighting, scheduled for 45 rounds, began. In the fourth round, after landing an uppercut, Johnson knew “… the old ship was sinking.”

In the fifteenth round, for the first time in his career, Jeffries went down. His managers threw in the towel. In defeat, Jeffries offered, “I could never have whipped Johnson … I couldn’t have reached him in a 1,000 years.”

____________________________________________________

Murry read his opponent well. Ali, out of work and out of money, accepts $10k to settle the suit. And agrees, for an undisclosed sum, to face Marciano in the Super Fight, a showdown between the last undefeated Heavyweight Champions.

By the time of the press conference, Marciano, 55 and close to fighting weight, sports a special toupee, made to stay on in the ring. Ali, all of 27, shows a little softness in the middle.

In the pre-fight news conference, Marciano offers respect for Ali. “He’s the fastest man on wheels … a scientific fighter.” Then, talking straight into the camera, he re-assures his followers:

I think it’s good that the computer is the one who makes the decision…there will be no prejudice in the fight.

Ali, grudgingly respectful of his opponent, has little patience for the silly questions:

Anyone who’s within arm’s reach of me … his brains are shook. No one as I’m tellin’ ya have ever touched my face.

All athletes lie about some part of their anatomy. Height is common; stretching it in boxing, sometimes shrinking it if you’re a power forward. Ali was 6’3” or there about.

Marciano managed to have his height listed at 5’11”. His weight, taken in front of audiences for each of his 49 professional fights, varied around 185 lbs., more cruiserweight than heavyweight.

But his height remained a controversy, especially as in the ring his crouching style brought him low, accentuating the size difference, making him look a foot shorter than Ali.

In secrecy, seventy rounds of sparring were filmed. The choreography is obvious but respectable. Yet, close eyes can see some feeling out. And gossip has it that more than once the fighters got beside themselves.

As early as round one, Ali learns something: All of his professional career, Marciano fought uphill against bigger men unfamiliar with a fighter who crouched so low.

Low, as Marciano said, to make himself a harder target. With his power, emanating from piston legs, coiled in his waist, ready to be funneled through short stumps of arms. As a heavyweight, Marciano had the shortest reach in modern boxing history.

But there he was, defying norms, teasing Ali with what looked to be an easy target. Tricking Ali into a looping right that sails high, allowing Marciano to step inside; halfway because he gets his left foot slightly behind Ali’s and his right foot between so that at once, Ali’s kidney is exposed to a left while his mid-section, in the instant before his right retreats, is open to the other fist, as powerful, a needy sportswriter imagined, as “… an armor-piercing shell.”

In the boxing clip, a smile crosses Ali, as though saying if this were real, I’ve made a mistake.

____________________________________________________

Rocco Francis Marchegiano trained in his backyard in Brockton, Ma., digging raw knuckles into a stuffed mailbag. After dropping out of high school and failing a tryout for the Cubs, Marchegiano changed his name and hired his childhood friend as his trainer. In January of 1969, Al Colombo tragically died in an industrial accident. Six months later, virtually the eve of the Super Fight, Rocky joined his trainer. Their statues, at Rocky Marciano High School, remain forever abreast.

All of Rocky’s friends shared stories about how tight he was with his money – his cash. Checks, it seems were too abstract. He gave them away, at times it’s been said, with shocking figures written on their faces. But to get him to part with his own green, stuffing his pockets as though he never trusted a soul, was harder than winning a match.

So it surprised no one when Marciano accepted an invitation to open a steak house in Iowa, owned by a ‘connected’ friend. Instead of buying a ticket on a commercial flight with a trained pilot, he pocketed his per diem and hitched a ride on a local Cessna flown by an inexperienced pilot, straight into a storm.

____________________________________________________

“Hi everybody this is Murry Woroner. We’re back again for the All-time Heavyweight Fight …”

Looking back, I am surprised about how much I knew and have since un-learned. Everything about the staging of that fight made sense to me: That it was priced so as to be reached only by those for whom it was orchestrated; those who knew why the fight was being staged, those who knew the outcome in advance.

Of course, we dynamically programmed the bouts so that after every punch there was less go in the fighter than before. That was our deterioration factor. We had to program data on his ability to take a solid right to the head, whether he had a glass chin, how well he could rally. We had to feed in killer-instinct data …

We just didn’t have enough raw data to absolutely program every move or every blow … Actually, it was a quasi-simulation program.”

I knew that then; knew nothing about computers save what I gleamed from the Jetsons Saturday morning cartoon and yet knew they were machines made by men out of their bias. And so I had no curiosity about the computer itself, no presaging of the future that I would one day be a part of.

I just knew why that computer, through the work of men, offered up that fight. Knew why the need to see Rocky win.

Ali and Marciano choreographed seven endings; logical in all regards – two knockouts each, two draws, one tie.

Ali, per his autobiography, says he sat in a theater on the night of the release – the only night the fight was shown as in the contracts, the prints were to be destroyed – and watched Marciano lay his image against the ropes with a series of shots, suggested by Ali, to choreograph his undoing.

Listening to the crowd cry foul, witnessing the cheapening of his reputation by his own hand – for what did he think those endings were for – he’s humiliated.

After watching all twenty-five feet of himself fall, Ali claims he knew not what the end would be, had always thought he’d win. “The computer,” he tried to explain, “was made in Alabama…”

Yet when told that in Europe, the larger audience, Marciano is the one falling in the 13th, Ali withdraws his suit.

____________________________________________________

After that fight, I was not surprised. Nor were the kids who fought in front of my apartments. Kids from half-families, surviving on welfare, our brains so filled with knowing how the world worked there was no room left to marvel at the computer.

As I write this, I am surprised. I have grown into a man who understands the arc of computer history but not of the history of those falling around me, casualties of something I believed long since cured.