by Leanne Ogasawara

1.

Of all the places I’ve never been, Borneo is my favorite.

I have several times been within spitting distance: to the Philippines—as far south as Panay; to the court cities of central Java and to the highlands of Sulawesi, in Indonesia. I’ve spent many happy days on Peninsular Malaysia. Have lived in Tokyo, Hong Kong, and Kaoshiung~~~But as they say, “Close, but no cigar!”

My college boyfriend was a great fan of Joseph Conrad. He wanted to follow in the great man’s footsteps. He planned it all out. We’d go up the Mahakam River. “More than a river, it’s like a huge muddy snake,” his eyes danced with excitement, “Slithering through the dense forest.” We talked about Borneo endlessly. He promised I would see Borneo’s great hornbills, wearing their bright orange helmets– with bills to match. And primates: maybe we would see a gibbon in the tangle of thick foliage –or an orangutan. There would be noisy parrots in the trees and huge butterflies with indigo wings like peacock feathers, fluttering figments of our imagination. He told me that nothing would make him happier than to see the forests of Borneo.

A cruel young woman, I vetoed Borneo –and dragged him off to Kashmir instead. And to make matters worse, a year later, Gavin Young came out with his highly acclaimed book, In Search of Conrad, in which he does just what my boyfriend had wanted to do: follow Conrad to that famed trading post up “an Eastern river.”

2.

2.

Recently, I re-read Eric Hansen’s travel classic, Stranger in the Forest. The book came out in the mid-80s. This was about ten years before I vetoed our trip to Borneo. It was also a time before the Internet and GPS. To prepare for his trip, Hansen had to go to a university library and read books, flip through journals, and consult maps—and to his great delight, he discovered there were still uncharted areas. And these were the very spots he wanted to see! Beginning his journey on the Malaysian side of Borneo, in Kuching, he traveled upriver on the Rajang (every bit as legendary as the Mahakam), and made his way inland toward the Highlands, where the indigenous Dayak peoples lived.

Did I mention he was mainly going on foot?

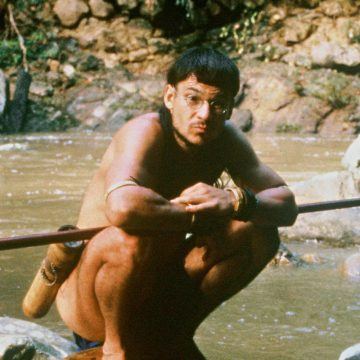

His trip occurred just a few years before Bruno Manser’s legendary ramble across Borneo. You’ve heard the expression “Fact is stranger than fiction?” Well, that term was invented for Swiss environmentalist, Bruno Manser’s life story. Arriving in Borneo in the mid-80s, within a year, he was living with one of the most elusive tribes in the highlands, the Penan. Carl Hoffman (who wrote the best seller, Savage Harvest) has just come out with a double biography called The Last Wild Men of Borneo about Bruno Manser and American tribal art dealer Michael Palmieri. The cover of the book has a photograph of Manser that I did not realize was a white man until I was nearly finished reading. Dressed in a loincloth and carrying a poison arrow quiver and blowpipe, his hair has been cut in the Dayak fashion, and he is shown squatting on a rock near the river’s edge. It is a touching photograph of a man who gave his life to fight for the rights of the indigenous peoples of the highlands.

For those who want to see what walking in the forest is actually like, they can take a look at the fourth documentary, “Dream Wanderers of Borneo,” in Lorne and Lawrence Blair’s Ring of Fire films. The book came out in 1988 and the book in 2003, based on their several month-long journey in the early 80s to find and stay with the nomadic Punan Dayaks. The brothers were themselves following in the footsteps of the Victorian naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace in his Malay Archipelago, who had discovered over 2,000 species of insects in the region. This is well shown in the brother’s video, as the insects are relentless. One of the brothers wonders if that is not the reason why Borneo was left alone for so long, for who could tolerate the bugs? At one point Lorne becomes temporarily blind for a half hour when something stings the back of his neck.

Even as early as 1980, logging was already a huge issue. In Japan, especially, environmentalists rightly bemoaned the destruction being caused by the timber industry—so much of that wood being imported into Japan (The majority is now being imported into China). Logging was pushing the indigenous Dayak peoples of the highland into greater and greater peril as the land they considered to be theirs was being destroyed. Water was contaminated and animals were dying in great numbers. Manser realized that a people who had lived harmoniously in the interior of the island for thousands of years were now in grave danger of being pushed out–all in the name of corporate greed.

And so he fought valiantly to bring their plight to the attention of the world—including climbing up a 30-foot-tall London lamppost outside of the media center covering the 1991 G7 Summit and unfurling a banner about Dayak rights and then the following year, paragliding into a crowded stadium during the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro. In 1992, after meeting Manser, Vice-President Al Gore introduced a resolution into the senate calling upon the government of Malaysia to protect the rights of the indigenous peoples and for Japan to look into its logging companies’ practices. By the mid-90s, Manser had become a serious headache to the huge logging industry in Malaysia and an embarrassment to the government. Manser was to disappear in 2000 and was officially pronounced dead in 2005 (though his body was never found).

3.

It is a tragic story, with the only possible silver-lining being that at least Manser was not around to see what happened next, when the palm oil industry came to town. I had began wondering how much of that Borneo my boyfriend dreamt of was left? So, I picked up The Wasting of Borneo, by Alex Shoumatoff (2017) and quickly realized the situation was far worse than I was imagining. A staff writer for the New Yorker, Shoumatoff has been a contributing editor at Vanity fair and Conde Nast traveler among others. A travel writer and environmentalist, he has been to Borneo several times. In this latest book, he begins his Borneo journey with a visit to Birute Galdikas at her Orangutan Care Center near the Tanjung Puting National Park in Central Kalimantan.

Have you heard of Leakey’s Angeles?

Anthropologist Louis Leakey had an unusual thought: what would happen if he sent three young women, mainly untrained in science, to go into the field to see what they see. The women being untrained would mean they had fewer preconceived notions, and he figured their observations would be valuable. The Angels were Jane Goodall (chimpanzees in Gombe Stream National Park in Tanzania), Dian Fossey (mountain gorillas in Rwanda), and Birute Galdikas in Borneo. Of the three, only Galdikas is still out there–not far from the original Camp Leakey in Borneo, where she now runs an orphanage for orangutans who have lost their mothers to poaching and fire.

And when I say fires, I mean fires so big they can be seen in space.

In many ways, the palm oil industry makes logging look like child’s play in the jungle. Slash and burn is only an understatement. A very significant percentage of the ancient rainforests on the island have already been destroyed (about 30%-50% and at this rate we will lose them all by 2050). Fires are set to prepare for monocrops. You get it: fires sending massive Co2 into the atmosphere resulting from clearing trees, which had they have been left standing in the ground would have helped lessen the carbon going into the atmosphere in the first place. Borneo’s rain forests are the oldest on the planet and contain what has one the highest densities of biodiversity in the world. So, this practice is a total lose-lose.

And for what?

Palm oil.

Palm oil.

Palm oil is a funny thing. This product that we never knew we needed thirty years ago is now in everything. From shampoo and toothpaste to every snack known to man– It is nearly impossible to avoid. Shoumatoff says he is down to a drop a week in toothpaste and shampoo… I don’t use it at all anymore. But it is really hard to avoid the stuff, since it is in everything… And so the destruction continues. After the forests are cleared, monocrop oil palms are planted, and this habitat destruction has pushed the island’s animals to the brink of extinction–including our cousins, the orangutans.

How can we continue with this destruction?

Sometimes we read op-ed pieces in places like the Guardian and New York Times about how our consumer choices don’t matter. We have to hit the systems that are causing the destruction. It’s true–without over-turning our current vulture-capitalism we won’t make huge dents; but at the same time, they don’t do us any favors by saying what we buy doesn’t matter. Because it does. Every time we vote with our dollars by consuming this palm oil poison, we are part of the problem. Even if just a small part of the problem, at the very least we are enablers. That is because when there is a market, it makes it that much harder to overturn these practices.

This is a point that Shoumatoff takes some time to make at the end of his sad, beautifully-written story.

4.

4.

In the end, my college boyfriend took his trip upriver in Borneo. I am happy he made it before it was too late. All I can do is sit here and write love letters to a vanishing world. I daydream of orchid-covered hills veiled in mist. And of fireflies that light up the jungle. I can almost hear the sound of Borneo’s famed birdsong; insects loudly humming; and sometimes when I close my eyes, I can catch the sound of a Bornean guitar and a dancer’s feet stamping rhythmically against the polished wooden floors of the longhouse, her small head adorned in black hornbill feathers, turning turning…

When you’re young, the world seems wide open. With nothing to stop you, anything seems possible. Reaching mid-life, however, it suddenly dawns on you that, no, you probably won’t see all the places you dreamt of when you were young. Aleppo and Damascus; Libya and the Sudan, these are some of the places I regret not seeing when I had the chance. It’s not just age, mind you, for places too can have bad luck. And the land you dreamt of visiting might in reality no longer exist.

A man I once knew told me that, “Waiting is a form of love.” (He would say this to all the women in his life). Well, I have waited for Borneo.

There is a word, solastalgia, that captures the feeling of loss due to environmental change. We are drowning in sadness for a warming earth and global extinction. How do we find the will to focus on one peculiar corner of the world? For me, Borneo conjures a place that is exotic, dangerous, and beautiful. It represents all the favorite places to which we have never been and never will go. When all the Borneos are gone, when all the wildness and danger and savage beauty is gone, what then will be left? A dancer with hornbill feathers, moving to a lonely guitar in our fading imagination of a vanishing world.

And so my love letter to Borneo is in my not going. It is in my refusal to consume any product with palm oil in it. And to keep this place, once described as an earthly paradise, close at heart. For of all places I’ll never see, Borneo is my favorite. Imagined and deeply loved, it is all the more treasured in my not going.

The Great Derangement: Fiction and Climate (Recommended Books)

Palm Oil was Supposed to Help Save the Planet. Instead it Unleashed a Catastrophe