by Philip Graham

I serve as the family cook as well as the family DJ, so no dinner party preparation is complete without a small stack of CDs waiting for guests to arrive. When the doorbell rings and my wife Alma walks to the front door to greet our earliest guests, I idle the burners on the stove and hurry to the living room stereo, where I press Play for the first CD. A song should already be in progress before the exchange of Hellos, because music, like furniture, is a form of home decoration, filling and defining silence the way a couch or chair fills and defines space. The music must be dialed low, just enough for a home to express quiet domestic welcome. I like to think that I’m long past my ancient feckless undergraduate days of booming a song through an open window.

I serve as the family cook as well as the family DJ, so no dinner party preparation is complete without a small stack of CDs waiting for guests to arrive. When the doorbell rings and my wife Alma walks to the front door to greet our earliest guests, I idle the burners on the stove and hurry to the living room stereo, where I press Play for the first CD. A song should already be in progress before the exchange of Hellos, because music, like furniture, is a form of home decoration, filling and defining silence the way a couch or chair fills and defines space. The music must be dialed low, just enough for a home to express quiet domestic welcome. I like to think that I’m long past my ancient feckless undergraduate days of booming a song through an open window.

Yet over dinner, rarely does someone ask, “What is that lovely music?” Such a longed-for question always fills me with joy—someone heard its beauty too!–and I’m happy to reply, “Oh, that’s Brian Eno’s Music for Airports,” or “We’re listening to the Afro-Spanish singer Buika Concha,” or “You like the Kora Jazz Trio, too?” Am I the only one who can be diverted from dinner chitchat by an airy chorus, or a husky vocal phrase, or a tack piano’s piquant modulation?

That magic question does get asked from time to time. I remember in particular one evening, many years ago, when I hit paydirt as guests passed serving plates and bowls back and forth at the dinner table and an austere mix of resonant metallic percussion, choral voices, an organ and a violin wafted from the living room.

“What are we listening to?” my old friend Bruce asked. Bruce! Of all my friends, I knew he had that question in him.

“It’s ‘La Koro Sutro,’ by a contemporary American composer, Lou Harrison.” Read more »

Perhaps imprudently, your humble blogger continues to toil in the philosophy mines for blogging material, even in this stressful time. And there will be such postage eventually, of that you can be sure! However, prudence enough remains to prevent him from posting half-baked nonsense; so in the interim, let us return once again to the podcast, and enjoy some fine music while we wait.

Perhaps imprudently, your humble blogger continues to toil in the philosophy mines for blogging material, even in this stressful time. And there will be such postage eventually, of that you can be sure! However, prudence enough remains to prevent him from posting half-baked nonsense; so in the interim, let us return once again to the podcast, and enjoy some fine music while we wait.

We have argued in

We have argued in

Sughra Raza. Island Pond Algae, Upstate NY. July 26, 2020.

Sughra Raza. Island Pond Algae, Upstate NY. July 26, 2020.

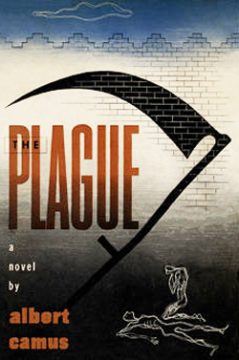

Nothing focuses minds like grave events that bring about severe disruption to everyday living. Over recent times, two major happenings, one with global and the other with more regional implications, have jolted people out of their complacency and compelled some reflection on unpredictability and uncertainty in life, and what is going on around us.

Nothing focuses minds like grave events that bring about severe disruption to everyday living. Over recent times, two major happenings, one with global and the other with more regional implications, have jolted people out of their complacency and compelled some reflection on unpredictability and uncertainty in life, and what is going on around us. When the Rajah’s barber could no longer keep the secret, he was seen darting by the sparrow in the tamarind, by the flinty owl in the giant oak that was surely a jinn’s abode, by a flock of hill mynahs flying through the buttery light of early spring. What was it that sent him bumbling through the jungle like that? Hours before, he had met the Rajah’s terrible gaze in the mirror when he discovered two sickle-shaped horns under his hair. This secret was as a rock he had swallowed, a rock he needed to expel. He was found panting by the fox of the jungle’s dank center, by a tightly knotted vine clutching a forgotten well. He saw that the well was old and there was bamboo growing in it. He saw it was safe and he screamed his fullest scream into the well: “the-Rajah-has-horns-on-his-head!” The bamboo had been thirsty for a secret and happily soaked it up, but the next day it was cut down by a flute maker who had been in search of just the right bamboo. Soon, all his fine bamboo flutes were sold. Then, all the new flutes of Jaunpur sang out the secret: “the-Rajah-has-horns-on-his-head!” The bamboo had been thirsty for a secret. The hapless barber had poured into it his last song.

When the Rajah’s barber could no longer keep the secret, he was seen darting by the sparrow in the tamarind, by the flinty owl in the giant oak that was surely a jinn’s abode, by a flock of hill mynahs flying through the buttery light of early spring. What was it that sent him bumbling through the jungle like that? Hours before, he had met the Rajah’s terrible gaze in the mirror when he discovered two sickle-shaped horns under his hair. This secret was as a rock he had swallowed, a rock he needed to expel. He was found panting by the fox of the jungle’s dank center, by a tightly knotted vine clutching a forgotten well. He saw that the well was old and there was bamboo growing in it. He saw it was safe and he screamed his fullest scream into the well: “the-Rajah-has-horns-on-his-head!” The bamboo had been thirsty for a secret and happily soaked it up, but the next day it was cut down by a flute maker who had been in search of just the right bamboo. Soon, all his fine bamboo flutes were sold. Then, all the new flutes of Jaunpur sang out the secret: “the-Rajah-has-horns-on-his-head!” The bamboo had been thirsty for a secret. The hapless barber had poured into it his last song.

Many social commentators in the claustrophobic gloom of their self-isolation have shown a tendency to write in somewhat feverish apocalyptic terms about the near future. Some of them expect the pre-existing dysfunctionalities of social and political institutions to accelerate in the post-pandemic world and anticipate our going down a vicious spiral. Others are a bit more hopeful in envisaging a world where the corona crisis will make people wake up to the deep fault lines it has revealed and try to mend things toward a better world. Some others take an intermediate position of what is called upbeat cynicism: hold out for things to be better but guess that will not happen (somewhat akin to Antonio Gramsci’s “pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will”).

Many social commentators in the claustrophobic gloom of their self-isolation have shown a tendency to write in somewhat feverish apocalyptic terms about the near future. Some of them expect the pre-existing dysfunctionalities of social and political institutions to accelerate in the post-pandemic world and anticipate our going down a vicious spiral. Others are a bit more hopeful in envisaging a world where the corona crisis will make people wake up to the deep fault lines it has revealed and try to mend things toward a better world. Some others take an intermediate position of what is called upbeat cynicism: hold out for things to be better but guess that will not happen (somewhat akin to Antonio Gramsci’s “pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will”). Throughout history there have been prophets of doom and prophets of hope. The prophets of doom are often more visible; the prophets of hope are often more important. The Danish economist Bjorn Lomborg is a prophet of hope. For more than ten years he has been questioning the consensus associated with global warming. Lomborg is not a global warming denier but is a skeptic and realist. He does not question the basic facts of global warming or the contribution of human activity to it. He does not deny that global warming will have some bad effects. But he does question the exaggerated claims, he does question whether it’s the only problem worth addressing, he certainly questions the intense politicization of the issue that makes rational discussion hard and he is critical of the measures being proposed by world governments at the expense of better and cheaper ones. Lomborg is a skeptic who respects the other side’s arguments and tries to refute them with data.

Throughout history there have been prophets of doom and prophets of hope. The prophets of doom are often more visible; the prophets of hope are often more important. The Danish economist Bjorn Lomborg is a prophet of hope. For more than ten years he has been questioning the consensus associated with global warming. Lomborg is not a global warming denier but is a skeptic and realist. He does not question the basic facts of global warming or the contribution of human activity to it. He does not deny that global warming will have some bad effects. But he does question the exaggerated claims, he does question whether it’s the only problem worth addressing, he certainly questions the intense politicization of the issue that makes rational discussion hard and he is critical of the measures being proposed by world governments at the expense of better and cheaper ones. Lomborg is a skeptic who respects the other side’s arguments and tries to refute them with data.