by Jochen Szangolies

Thomas Bayes and Rational Belief

When we are presented with two alternatives, but are uncertain which to choose, a common way to break the deadlock is to throw a coin. That is, we leave the outcome open to chance: we trust that, if the coin is fair, it will not prefer either alternative—thereby itself mirroring our own indecision—yet yield a definite outcome.

This works, essentially, because we trust that a fair coin will show heads as often as it will show tails—more precisely, over sufficiently many trials, the frequency of heads (or tails) will approach 1/2. In this case, this is what’s meant by saying that the coin has a 50% probability of coming up heads.

But probabilities aren’t always that clear cut. For example, what does it mean to say that there’s a 50% chance of rain tomorrow? There is only one tomorrow, so we can’t really mean that over sufficiently many tomorrows, there will be an even ratio of rain/no rain. Moreover, sometimes we will hear—or indeed say—things like ‘I’m 90% certain that Neil Armstrong was the first man on the Moon’.

In such cases, it is more appropriate to think of the quoted probabilities as being something like a degree of belief, rather than related to some kind of ratio of occurrences. That is, probability in such a case quantifies belief in a given hypothesis—with 1 and 0 being the edge cases where we’re completely convinced that it is true or false, respectively.

Beliefs, however, unlike frequencies, are subject to change: the coin will come up heads half the time tomorrow just as well as today, while if I believe that Louis Armstrong was the first man on the moon, and learn that he was, in fact, a famous Jazz musician, I will change my beliefs accordingly (provided I act rationally).

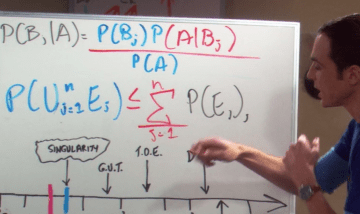

The question of how one should adapt—update, in the most common parlance—one’s beliefs given new data is addressed in the most famous legacy of the Reverend Thomas Bayes, an 18th century Presbyterian minister. As a Nonconformist, dissent and doubt were perhaps baked into Bayes’ background; a student of logic as well as theology, he wrote defenses of both God’s benevolence and Isaac Newton’s formulation of calculus. His most lasting contribution, however, would be a theorem that gives a precisely quantifiable means of how evidence should influence our beliefs. Read more »