by David Oates

My decision not to go into downtown Portland for the protest demonstration has held up for four weeks now. The Federal provocateurs have finally begun to leave, and the threat of violence has been reduced to comparative insignificance. . . so it seems that if I were to show up now, it would merely underline that I am a craven fair-weather sort of progressive. That die is cast.

What have I been doing instead? Well, same as everybody. Sheltering in place. Cooking dinner. Trying to stay on my path. I’m a writer born in 1950, so I’m past the ditch-digging and hustling part of my life. But my path hasn’t changed.

I read things. I write poems or essays. I think about that next book. I take long walks to mull it over. I come back to our quiet, clean-but-becoming-threadbare home, ascend the stairs to my cluttered study, find the book or page or little stack of half-realized ideas, and make some tiny increment of progress. Two words that fit together. Two ideas. Two sentences. This is my near horizon.

It feels very far indeed from the Federal Courthouse. The anger of Black Lives Matter (which makes sense to me). The anger of Trumps and Trumpies (which seems evil and hard to account for). Just two miles from my house – I’ve walked it often. Across an elm-shaded neighborhood. Over the Hawthorne Bridge. And then there I am, staring at the plinth where the bronze elk ought to be standing. The boarded-up shops. The beaten-brown grass. The sprawl and slash of graffiti covering nearly every surface.

I’ve been there by day, but never at night.

This is my far horizon: discord, the derangement of politics, slogans, lies and delusions, conflict, power plays. Shouting. Orderly protest. State-organized cruelty. Aspiration for democracy. Truncheoning of democracy.

* * *

How to navigate between and among these worlds? Flailingly is my usual answer, as it for most of us. Just muddling along.

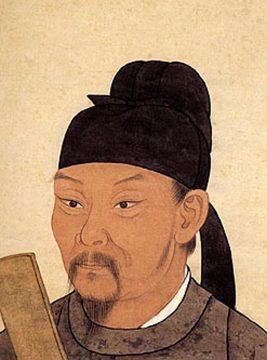

But a Chinese poet from the 700s is also, often, my guide: Tu Fu, a minor court official of the Tang era. A wry, thoughtful guy who lived on a houseboat and liked to drink.

On his public horizon were nearly constant insurrection and war. And of course palace politics. But close by – a path with flowers in spring. The sound of chopping wood echoing in a forest. The embrace of an old friend. What pierces my heart is how present in the moment he is. Some passages feel they could have been written last night.

“Sunset glitters on the beads

of the curtains. Spring flowers

bloom in the valley. The gardens

along the river are filled

with perfume. Smoke of cooking

fires drifts over the slow barges.

Sparrows hop and tumble in

the branches…”

In moments like this Tu Fu becomes our contemporary. As a writer – as a human – I am always brought to this still place by his work, where the least detail may be full of dignity and weight. What else ask for from writing?

And yet beyond this astonishing immediacy, Tu Fu also teaches me about reckoning with the larger struggle that goes on around us – that public horizon. He does not reconcile the tension between the private moment and the public turmoil. He simply registers the disjunction. No pat answer, no easy doctrine or partisan retort. Just the painful reality: history grinds remorselessly along while us mortals try to stay out of its way.

For instance, Tu Fu begins a short poem called “Moon Festival” with what must be standard poetic observations:

“The autumn constellations

begin to rise. The brilliant

moonlight shines on the crowds. . .”

But soon he personalizes this perhaps generic scene:

“. . . The silver brilliance

only makes my hair more white. . .”

And lastly he contrasts the peaceful night-and-nature scene with a wrenching recollection that pulls him back from pastoral reverie into political reality:

“I know that the country is

overrun with war. The moonlight

means nothing to the soldiers

camped in the western deserts.”

This is the moment in Tu Fu that teaches me the most. The political frames the pastoral in the end. That feeling – that sinking in the heart – concludes many of his poems. First he gives the beautiful moment, evoking its universality. (Indeed, the “universe” is often an explicit player: the moon and stars that seem to ask us for large and worthy thoughts.) But then, with a thump, we are brought back to the earthly reality, that we are embedded in time and must also suffer history’s madness and destruction.

Yet these are not cynical poems! The poem never aims to mock or undercut the beautiful moment. The point is to remember that such moments coexist with human violence and injustice that may rip through life at any moment (or hold off, if you’re lucky, for a little while longer). What Tu Fu teaches is to carry these opposites in tension with each other.

Life is hard and unjust; life is beautiful. Both statements are true. And to read the poetry of Tu Fu is to practice the difficult art of balance.

“Autumn daisies had begun to nod

among crushed stones wagons had passed. . .

secret things could still bring me joy!”

I know of no poet who captures this duality with more vividness and immediacy. When I fear for my country – I remember Tu Fu looking at the red leaves of autumn. The moonlight on the water. The way he’s really there. . . while just off stage but within hearing distance, the roar of battle rages on. And the way he then remembers the battered soldiers who will, in a day or two, come dragging up the road past him.

There’s often a humane connectedness in Tu Fu’s detachment. I could learn from that, too.

* * *

It is hard to write poetry in the atmosphere of corrupt sickness that has emanated from our White House for the last three years. After the breakthroughs of the Obama years – at last a solid counterword against our history of racism – the steady hand governing a long economic recovery – the achievement of a healthcare system including millions formerly left out. . . it seems unaccountable. I feel whipsawed, disoriented. Can people really be so blind and so vicious? The answer from history is a bemused, “Well of course. Where have you been?”

Like us, Tu Fu experienced governance that was gloriously competent and benevolent – and then, soon after, hopelessly corrupt and deranged. For the forty-three year reign of the so-called “Glorious Monarch” Ming Huang (reigned 713-56) spanned both extremes. The translator Arthur Cooper depicts the emperor’s first decades as a “model of Confucian. . . rectitude. Administration, communications and education were improved beyond any precedent.” Sciences and arts flourished. The two giants of Chinese poetry appeared, Tu Fu and Li Po.

Yet in the 730s, the emperor began a bewildering decline. The death of his favorite concubine seemed to tip him into unending weirdness. He schemed to steal a wife from his own son, obsessing over her “to the point of madness,” as Cooper says. By the 740s court life had became increasingly extravagant, with heavy taxes to support it, while military adventurism ate up the lives of younger generations and sparked continual wars and insurrections.

Truly, Tu Fu experienced the extremes. And he clearly understood that the disappointment and turmoil of public affairs could not be allowed to poison the private life. With rueful honesty, he occupies two worlds in his poetry, two horizons.

* * *

It seems to me that each of us is many things, a set of strangely separate, strangely overlapping worlds. That, for instance, each of the senses has a different horizon.

That gray-blue rim of the ocean on a fair day – that’s the horizon of vision. It can go far. It wants to! Though on a neighborhood street it may become parochial, crowded close by street-trees and the angular jut of rooftops. Yet just above. . . the sky. The stars.

But the horizon of touch is always near, intimate. A fingertip. The soft of the cheek. A hand, warm, touching the nape of your neck.

And between these extremes: hearing that might carry a note from quite far, filtered and perhaps enriched in its approach by other sounds sharper and closer, a door-slam across the street, the ruff of an elbow against a shirt, the scrape of your chair. How hard to shut out sound! We are unsupplied with ear-lids. Sound arrives all together, mixed like sonic perfume, coarse and melodious compounded, whisper from the next pillow and alarm bell from a mile away.

So when I say that the Portland protest is my far horizon, and the daily life of quiet consideration my near one, you’ll understand what I mean. Night by night I hear the echo of chanting, the muffled boom of. . . I hardly dare imagine what. It can be strange to look up from my desk, momentarily connected. Wondering what I ought to be doing instead.

* * *

The poems of Tu Fu came to me, decades ago, though poet Kenneth Rexroth’s 1971 book One Hundred Poems from the Chinese. His translations are often, as he puts it, “very free,” but they have the advantage of feeling like poetry, not translation. They are immediate and vivid. So here, to conclude, is one poem in its entirety. It catches the mood of public decline, the general atmosphere of suspicion and oppression. And the quietly detached persistence of the writer.

“Night in the House by the River”

“It is late in the year;

Yin and Yang struggle

In the brief sunlight.

On the desert mountains

Frost and snow

Gleam in the freezing night.

Past midnight,

Drums and bugles ring out,

Violent, cutting the heart.

Over the Triple Gorge the Milky Way

Pulsates between the stars.

The bitter cries of thousands of households

Can be heard above the noise of battle.

Everywhere the workers sing wild songs.

The great heroes and generals of old time

Are yellow dust forever now.

Such are the affairs of men.

Poetry and letters

Persist in silence and solitude.”

* * *

But in the end I must ask: how do Tu Fu’s lessons of balance and detachment help me reckon with my failure to show up for the progressive moment of truth that’s playing out in my own town? After all, we confront not an entrenched monarchy, but a system that at least aspires to democracy. It’s designed (on paper) to be influenced by nobodies like me. Surely more is required of me!

I have further to go. So I turn to an American writer I’ve adored and emulated for my whole adult life, one from much closer to our own times – Henry David Thoreau. He will be my guide in Part Two of this essay, four weeks from now.

Note on sources: I’ve quoted poems as translated by Kenneth Rexroth and one (“autumn daisies. . .”) by Arthur Cooper. In both cases I’ve lightly modified language or presentation (for instance, removing capitalization in some cases at the start of each line) to make poems more consistent with current poetic practices. Cooper’s book Li Po and Tu Fu (Penguin, 1973) also provides background and biographical information I’ve used.