by Dick Edelstein

When an overdose of reading the news causes the horrors of today’s global politics to hit my psyche like a flurry of blows in a boxing ring, attending a poetry event can remind me of the value of life’s small pleasures and reaffirm my faith in the good intentions of at least some parts of humanity.

Recently I attended the Sunflower Sessions, a poetry reading held regularly in Dublin that enjoys a certain status among local poetry buffs. Its organizers make a concerted effort to maintain the reputation and continuity of the readings, taking their responsibility to heart as a sort of sacred trust. This sentiment was reflected by quite a few of the people who read their poetry that night when they used part of their reading time to thank the organizers of the event for their conscientious efforts.

Twenty years is a long time for a regular poetry event to persist and the three Dubliners of long experience who organize it are only too conscious of the pitfalls. Success depends on constantly attracting new participants while retaining the interest of poets and spectators who have already attended many times. Also, there is the precariousness of having to depend on the generosity of pub owners or managers to provide a free venue. Master of ceremonies Declan McLoughlin, while promoting FLARE, the quarterly poetry magazine associated with the event, admonished his audience, “If you only have enough money to buy the magazine or a pint, then get the pint because since COVID it’s become nearly impossible to find a free venue.”

The success of this venture can teach us a few things about the appeal of poetry reading in an age where the mass media strongly compete and generational change drives cultural preferences. Although these sessions are popular among poets who have passed into middle age and beyond, the organizers make an effort to appeal to the younger generations, making it clear that the door is wide open to them and to participants from all parts of Dublin society, including those whose native language is not English. While this is not an easy task, their efforts continue to prosper as they manage to bring together poets and listeners from different social groups and generations. In the face of these challenges, keeping the reading series going is like cultivating a delicate flower. Read more »

Every neighborhood seems to have at least one. You know him, the walking guy. No matter the time of day, you seem to see him out strolling through the neighborhood. You might not know his name or where exactly he lives, but all your neighbors know exactly who you mean when you say “that walking guy.” This summer, that became me.

Every neighborhood seems to have at least one. You know him, the walking guy. No matter the time of day, you seem to see him out strolling through the neighborhood. You might not know his name or where exactly he lives, but all your neighbors know exactly who you mean when you say “that walking guy.” This summer, that became me.

For some time there’s been a common complaint that western societies have suffered a loss of community. We’ve become far too individualistic, the argument goes, too concerned with the ‘I’ rather than the ‘we’. Many have made the case for this change. Published in 2000, Robert Putnam’s classic ‘Bowling Alone: the collapse and revival of American community’, meticulously lays out the empirical data for the decline in community and what is known as ‘social capital.’ He also makes suggestions for its revival. Although this book is a quarter of a century old, it would be difficult to argue that it is no longer relevant. More recently the best-selling book by the former Chief Rabbi Jonathan Sacks, ‘Morality: Restoring the Common Good in Divided Times’, presents the problem as one of moral failure.

For some time there’s been a common complaint that western societies have suffered a loss of community. We’ve become far too individualistic, the argument goes, too concerned with the ‘I’ rather than the ‘we’. Many have made the case for this change. Published in 2000, Robert Putnam’s classic ‘Bowling Alone: the collapse and revival of American community’, meticulously lays out the empirical data for the decline in community and what is known as ‘social capital.’ He also makes suggestions for its revival. Although this book is a quarter of a century old, it would be difficult to argue that it is no longer relevant. More recently the best-selling book by the former Chief Rabbi Jonathan Sacks, ‘Morality: Restoring the Common Good in Divided Times’, presents the problem as one of moral failure.

Sughra Raza. Nightstreet Barcode, Kowloon, January 2019.

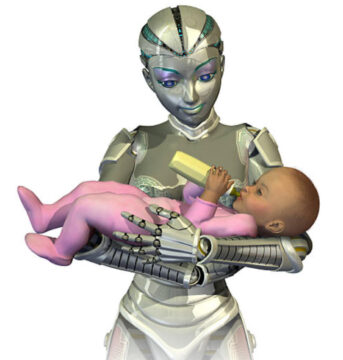

Sughra Raza. Nightstreet Barcode, Kowloon, January 2019. At a recent conference in Las Vegas, Geoffrey Hinton—sometimes called the “Godfather of AI”—offered a stark choice. If artificial intelligence surpasses us, he said, it must have something like a maternal instinct toward humanity. Otherwise, “If it’s not going to parent me, it’s going to replace me.” The image is vivid: a more powerful mind caring for us as a mother cares for her child, rather than sweeping us aside. It is also, in its way, reassuring. The binary is clean. Maternal or destructive. Nurture or neglect.

At a recent conference in Las Vegas, Geoffrey Hinton—sometimes called the “Godfather of AI”—offered a stark choice. If artificial intelligence surpasses us, he said, it must have something like a maternal instinct toward humanity. Otherwise, “If it’s not going to parent me, it’s going to replace me.” The image is vivid: a more powerful mind caring for us as a mother cares for her child, rather than sweeping us aside. It is also, in its way, reassuring. The binary is clean. Maternal or destructive. Nurture or neglect. With In the New Century: An Anthology of Pakistani Literature in English, Muneeza Shamsie, the time‑tested chronicler of Pakistani writing in English, presents what is arguably the definitive anthology in this genre. Across her collections, criticism, and commentary, Shamsie has chronicled, championed, and clarified the growth of a literary tradition that is vast but, in many ways, still nascent. If there is one single volume to read in order to grasp the breadth, complexity, and sheer inventiveness of Pakistani Anglophone writing, it would be this one.

With In the New Century: An Anthology of Pakistani Literature in English, Muneeza Shamsie, the time‑tested chronicler of Pakistani writing in English, presents what is arguably the definitive anthology in this genre. Across her collections, criticism, and commentary, Shamsie has chronicled, championed, and clarified the growth of a literary tradition that is vast but, in many ways, still nascent. If there is one single volume to read in order to grasp the breadth, complexity, and sheer inventiveness of Pakistani Anglophone writing, it would be this one.

In my last

In my last

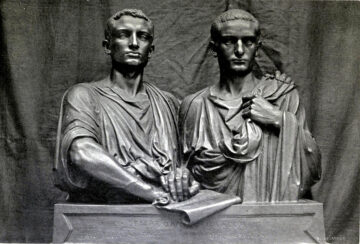

In the first part of this column last month, I set out the ways in which the separation of powers among the three branches of American government is rapidly being eroded. The legislative branch isn’t playing its part in the system of “checks and balances;” it isn’t interested in checking Trump at all. Instead it publicly cheers him on. A feckless Republican Congress has essentially surrendered its authority to the executive.

In the first part of this column last month, I set out the ways in which the separation of powers among the three branches of American government is rapidly being eroded. The legislative branch isn’t playing its part in the system of “checks and balances;” it isn’t interested in checking Trump at all. Instead it publicly cheers him on. A feckless Republican Congress has essentially surrendered its authority to the executive.