by Steve Szilagyi

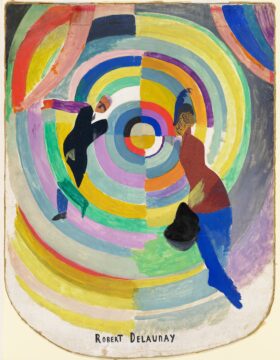

I’m writing a Broadway musical about Hilma af Klint, the Swedish painter who anticipated the entire aesthetics of the 20th century before 1915. Her rediscovery in the 1980s scrambled the timeline of modern art history. My creation isn’t going to be one of those post-Lloyd Webber mega-musicals, but something more along the lines of Cole Porter or Richard Rodgers, with unforgettable songs like “I Enjoy Being a Girl.”

Why af Klint? Why Broadway? It’s not like she’s being ignored. After all, she has splashy shows at the Guggenheim Museum and the Tate Modern. The Swedes make a gorgeously respectful movie about her life (Hilma), and MoMA currently has a show of her least interesting works running till the end of September, 2025. There’s even a graphic novel (The Five Lives of Hilma af Klint by Philipp Deines).

But for all that, I still feel that people don’t get her. Af Klint isn’t some tame artist to be hung alongside stale contemporaries like Piet Mondrian and packed away in a catalogue raisonné. She’s a crazy woman, running wild with an axe through the history of art, like Carrie Nation wrecking an old-time saloon. She trashes the accepted timelines, makes a shambles of avant-garde pretensions – and I, for one, won’t be happy until I see the 20th century artistic canon lying in shreds under the feet of her gold statue in the Parthenon.

Her mad, mad world. Here’s the thing: Hilma af Klint is impossible to explain in any sensible way. Born into an upper-middle class Stockholm family, she goes to art school and has some success painting ho-hum landscapes, portraits and flowers. Then, at age 40, she seemingly loses her mind. She starts going to séances, hearing voices, and is soon in the thrall of a gang of disembodied spirits who call themselves The High Masters. Their leader, Amaliel, is the number two power in the universe. (Technically, he reports to Jesus.) Amaliel reveals knowledge to Hilma that has been hidden since the beginning of time, and orders her to write it down. He also commands her to forget everything she knows about art, and re-invent painting from scratch – under his direction. Read more »

by David J. Lobina

by David J. Lobina

Hebrew or English?

Hebrew or English? Sughra Raza. On The Rocks at Lake Champlain. August 22, 2025.

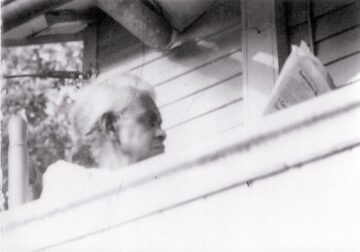

Sughra Raza. On The Rocks at Lake Champlain. August 22, 2025. reat-grandmother Emmaline might have loved it too. Born enslaved, she started anew after the Civil War, in what had become West Virginia. There she had a daughter she named Belle. As the family story has it, Emmaline had a hope: Belle would learn to read. Belle would have access to ways of understanding that Emmaline herself had been denied. We have just one photograph of Belle, taken many years later. Here it is. She is reading.

reat-grandmother Emmaline might have loved it too. Born enslaved, she started anew after the Civil War, in what had become West Virginia. There she had a daughter she named Belle. As the family story has it, Emmaline had a hope: Belle would learn to read. Belle would have access to ways of understanding that Emmaline herself had been denied. We have just one photograph of Belle, taken many years later. Here it is. She is reading.

I started reading Leif Weatherby’s new book, Language Machines, because I was familiar with his writing in magazines such as The Point and The Baffler. For The Point, he’d written a fascinating account of Aaron Rodgers’ two seasons with the New York Jets, a story that didn’t just deal with sports, but intersected with American mythology, masculinity, and contemporary politics. It’s one of the most remarkable pieces of sports writing in recent memory. For The Baffler, Weatherby had written about the influence of data and analytics on professional football, showing them to be both deceptive and illuminating, while also drawing a revealing parallel with Silicon Valley. Weatherby is not a sportswriter, however, but a Professor of German and the Director of Digital Humanities at NYU. And Language Machines is not about football, but about artificial intelligence and large language models; its subtitle is Cultural AI and the End of Remainder Humanism.

I started reading Leif Weatherby’s new book, Language Machines, because I was familiar with his writing in magazines such as The Point and The Baffler. For The Point, he’d written a fascinating account of Aaron Rodgers’ two seasons with the New York Jets, a story that didn’t just deal with sports, but intersected with American mythology, masculinity, and contemporary politics. It’s one of the most remarkable pieces of sports writing in recent memory. For The Baffler, Weatherby had written about the influence of data and analytics on professional football, showing them to be both deceptive and illuminating, while also drawing a revealing parallel with Silicon Valley. Weatherby is not a sportswriter, however, but a Professor of German and the Director of Digital Humanities at NYU. And Language Machines is not about football, but about artificial intelligence and large language models; its subtitle is Cultural AI and the End of Remainder Humanism.