by Godfrey Onime

At the physicians’ lounge recently, a colleague asked me, “How are the new interns? Aren’t you glad another July is over?”

I told him that our new class of first-year medical residents, or interns as they are commonly called, seemed quite strong. As for his celebratory comments about the vanquishing of July, I knew what he meant. After all, a common sage in American teaching hospitals is, “Don’t get sick in July.” The reason for this sentiment is because that’s when most of the doctors are the most green, or inexperienced.

It happens that when we consider medical errors, the level of experience of a doctor or other healthcare providers — as with any profession for that matter — is quite important. Less experience often equals more mistakes – from writing to accounting to carpentry. These screwups can become learning opportunities for these professionals. But medicine is different. Often, people die.

The so-called July effect in American teaching hospitals is one example of how inexperience can come to bear in the vexing world of medical errors. For one, July 1st or thereabout is the date when fresh medical school graduates transform into new interns, ready to practice — on you. That’s when they begin to zig-zag about the hospitals at frenzied paces in their yet shinny, starched white coats and introducing themselves as Dr. Superman (or woman). To truly understand the forces at play here, let’s for a moment get into the head of the new intern. Read more »

One remarkable redeeming feature of my dingy neighborhood in Kolkata was that within half a mile or so there was my historically distinctive school, and across the street from there was Presidency College, one of the very best undergraduate colleges in India at that time (my school and that College were actually part of the same institution for the first 37 years until 1854), adjacent was an intellectually vibrant coffeehouse, and the whole surrounding area had the largest book district of India—and as I grew up I made full use of all of these.

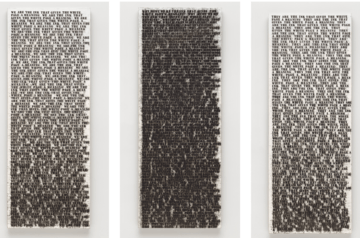

One remarkable redeeming feature of my dingy neighborhood in Kolkata was that within half a mile or so there was my historically distinctive school, and across the street from there was Presidency College, one of the very best undergraduate colleges in India at that time (my school and that College were actually part of the same institution for the first 37 years until 1854), adjacent was an intellectually vibrant coffeehouse, and the whole surrounding area had the largest book district of India—and as I grew up I made full use of all of these. Unlike her previous exhibit, James chose not to explicitly market

Unlike her previous exhibit, James chose not to explicitly market

The view that everyone who is capable has a basic duty to work and not be idle is the main tenet of what we call the work ethic. Closely related to this are two other ideas:

The view that everyone who is capable has a basic duty to work and not be idle is the main tenet of what we call the work ethic. Closely related to this are two other ideas:

When I was 12 my parents fought, and I stared at the blue lunar map on the wall of my room listening to Paul Simon’s “Slip Slidin’ Away” while their muffled shouts rose up the stairs. As I peered closely at the vast flat paper moon—Ocean Of Storms, Sea of Crises, Bay of Roughness—it swam, through my tears, into what I knew to be my future, one where I alone would be exiled to a cold new planet. But in fact it was just an argument, and my parents still live together—more or less happily—in that same house where I was raised.

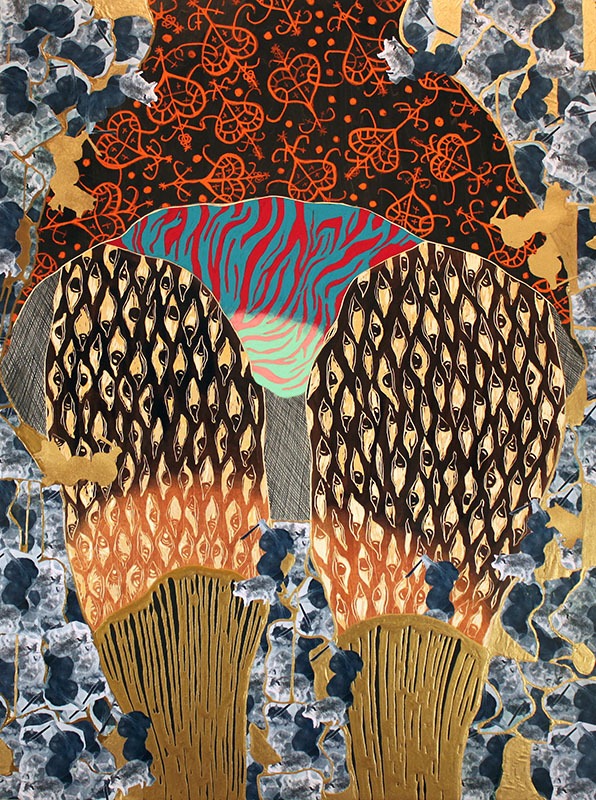

When I was 12 my parents fought, and I stared at the blue lunar map on the wall of my room listening to Paul Simon’s “Slip Slidin’ Away” while their muffled shouts rose up the stairs. As I peered closely at the vast flat paper moon—Ocean Of Storms, Sea of Crises, Bay of Roughness—it swam, through my tears, into what I knew to be my future, one where I alone would be exiled to a cold new planet. But in fact it was just an argument, and my parents still live together—more or less happily—in that same house where I was raised. Didier William. Ezili Toujours Konnen, 2015.

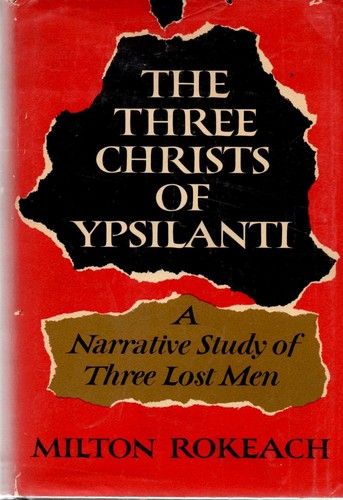

Didier William. Ezili Toujours Konnen, 2015. As an undergraduate History major, I reluctantly dug up a halfway natural science class to fulfill my college’s general education requirement. It was called Psychology as a Natural Science. However, the massive textbook assigned to us turned out to be chock full of interesting tidbits ranging from optical illusions to odd tales. One of the oddest was the story of Leon, Joseph, and Clyde: three men who each fervently believed he was Jesus Christ. The three originally did not know each other, but a social psychologist named Milton Rokeach brought them together for two years in an Ypsilanti, Michigan mental hospital to experiment on them. He later wrote a book titled The Three Christs of Ypsilanti.

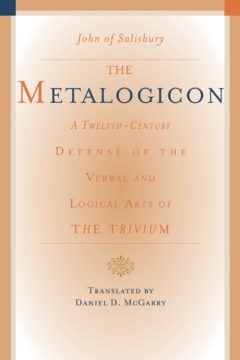

As an undergraduate History major, I reluctantly dug up a halfway natural science class to fulfill my college’s general education requirement. It was called Psychology as a Natural Science. However, the massive textbook assigned to us turned out to be chock full of interesting tidbits ranging from optical illusions to odd tales. One of the oddest was the story of Leon, Joseph, and Clyde: three men who each fervently believed he was Jesus Christ. The three originally did not know each other, but a social psychologist named Milton Rokeach brought them together for two years in an Ypsilanti, Michigan mental hospital to experiment on them. He later wrote a book titled The Three Christs of Ypsilanti. “I am by nature too dull to comprehend the subtleties of the ancients; I cannot rely on my memory to retain for long what I have learned; and my style betrays its own lack of polish.”

“I am by nature too dull to comprehend the subtleties of the ancients; I cannot rely on my memory to retain for long what I have learned; and my style betrays its own lack of polish.”

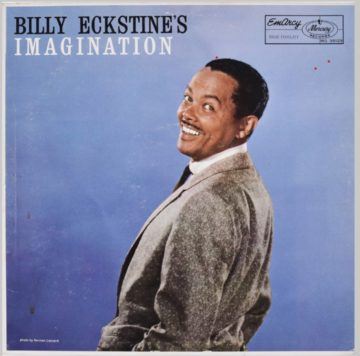

On August 17, 1977, I stopped in as usual at our neighbors’ house, to while away the summer day with my younger brother and sister until our mother’s return home from the university. Our friends – two sets of twins and one singleton – were home-schooled by their mother, and we were all having a summer staycation in any case, so there was always somebody at their house, and a reliably lively time to be had. What met me when I walked into the kitchen that morning, however, was an unaccustomed stillness. All five young people were hovering around the door to the living room while their mother sat at the kitchen table, hunched over a newspaper. “Elvis is dead,” whispered the singleton. Presley had died the day before, in Memphis, in the early afternoon of August 16; but the headlines, and President Carter’s address, would be that day’s news, on the outskirts of Vancouver as elsewhere around the world.

On August 17, 1977, I stopped in as usual at our neighbors’ house, to while away the summer day with my younger brother and sister until our mother’s return home from the university. Our friends – two sets of twins and one singleton – were home-schooled by their mother, and we were all having a summer staycation in any case, so there was always somebody at their house, and a reliably lively time to be had. What met me when I walked into the kitchen that morning, however, was an unaccustomed stillness. All five young people were hovering around the door to the living room while their mother sat at the kitchen table, hunched over a newspaper. “Elvis is dead,” whispered the singleton. Presley had died the day before, in Memphis, in the early afternoon of August 16; but the headlines, and President Carter’s address, would be that day’s news, on the outskirts of Vancouver as elsewhere around the world.