by Dick Edelstein

Not all jazz fans today will understand why an ultra-talented singer and musician like Billy Eckstine aspired to be a famous crooner. But his full, rich bass-baritone voice was ideally suited to that singing style – his voice was as smooth as that of Der Bingle, as Bing Crosby was affectionately known in those days. And crooners were the most admired singers in the 1940s, although it hardly escaped notice that they were all white men. Crosby topped the list of popular crooners – he was idolized by Sinatra – and his style was not merely influenced by jazz; he had built his reputation by fronting prominent jazz bands like the Paul Whiteman Orchestra, whose music suited the taste of white America. Crosby was good at that style of singing, sure, but Billy Eckstine could do as well without breaking a sweat and he wanted to prove it.

In a previous article I discussed how Billie Holiday’s vocals reflected the sound of horn solos. Eckstine, a friend of hers and a contemporary, was part of that story. An innovator, like Holiday, he too incorporated horn styling into his vocals, particularly when he was singing big band arrangements. This came naturally enough since he was a talented horn player who regularly performed on trumpet and trombone. His singing style was not like Holiday’s, but each found their own way of bringing the sound and feeling – and the excitement – of horns into their vocals. Eckstine didn’t imitate Holiday’s mercurial rhythmic shifts and unusual inflections; his vocals sounded more like studied compositions, ornamented with his faultless vibrato, which industry figures called the widest in the business. What the two singers had in common was their use of vocal styling to give expression to lyrics as they incorporated up-to-the-minute styles like progressive jazz and bebop into their expanded palette of vocal effects. Also, both of them were not only composers of popular hits, but successful lyricists as well.

So how great a singer was Eckstine?

I’ll discuss that before commenting on his career as a band leader and solo artist. It was probably no accident that he chose a song with lyrics written by Bing Crosby himself to showcase his crooning talent. When he croons the title line I don’t stand a ghost of a chance with you, he sneaks up to the high note on ghost, underplaying it like Michael Jordan lifting in an easy lay-up. Despite evident differences, this bit of singing reminds me of opera great Placido Domingo singing in his well-known role as Don Jose in Carmen. When he intones la fleur que tu m’avais jetée, slightly inflecting the note on fleur, underemphasizing it as he imparts a sweet timbre to the drawn-out note, opera fans go home feeling that hearing that was worth the price of admission. I get that feeling hearing Billy Eckstine perform one of his greatest songs – a song composed by Der Bingle himself. And I’m not the only one who feels that way since quite a few of Eckstine’s solo recordings were million-selling records.

In 1939, Eckstine began working as a featured vocalist in Earl “Fatha” Hines’ orchestra while also playing trumpet. As he cut his teeth musically in the most important jazz band since Louis Armstrong’s, he picked up on the new sound being brewed up in late night jam sessions by the future creators of bebop, whom he would soon hire to form his own band in 1943. “When I had my band, we were pioneering that sound, but they weren’t big names. They were just guys starting out”, said Eckstine, referring to Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie, who were soon joined by Art Blakey and Miles Davis. Eventually Sarah Vaughan, Dexter Gordon, Gene Ammons, Wardell Gray and other greats would come on board as Eckstine led the first bebop orchestra. This exciting band was ahead of its time musically, but the new sound proved to be not very commercial, so in 1947 Eckstine moved on to a solo career singing popular ballads, eventually rivalling Frank Sinatra in sales and popularity.

His solo recordings, with their lush, sophisticated orchestral arrangements, were far more successful than his band recordings had been. He released more than a dozen hit singles during the late 1940s, opening the way for Black singers to become popular crooners. His biographer Cary Ginell considered him the Jackie Robinson of popular music: “Before he came along, Blacks, they would either sing blues or they would be in jazz bands, or they would sing in vocal groups, like the Mills Brothers. Or as a novelty singer. But they were not permitted to enter the domain of Perry Como. And Eckstine was the first one to successfully do that.”

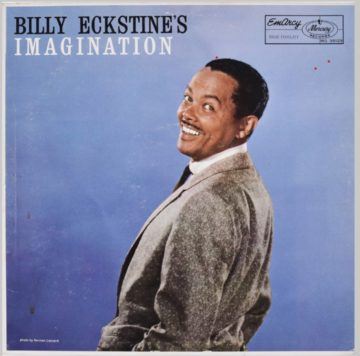

Riding a wave of popularity, the handsome and talented Eckstine became an idol, mobbed by fans wherever he appeared. Lucrative TV appearances and film roles were under discussion as Eckstine envisioned a career in film and television that seemed just around the corner. But this scenario changed suddenly when LIFE Magazine published a profile of him in April, 1950, featuring a photograph of Eckstine leaving a New York City nightclub surrounded by a crowd of white teenage girls. One of them was laughing, with her hand on his shoulder and her head leaning against his chest. The encounter was entirely innocent, but as Tony Bennett recalled, “It changed everything … Before that, he had a tremendous following … and it just offended the white community.” You could hear the doors slamming shut as Eckstine’s film and television prospects evaporated before his new career had even begun.

But Billy Eckstine had opened doors, even if he was not able to walk through them. Six years later, Nat King Cole became the first African American to host a network TV show. Significantly, he was a crooner too. Composer and band leader Quincy Jones, remarked, looking back over his own career, “I looked up to Mr. B as an idol. I wanted to dress like him, talk like him, pattern my whole life as a musician and as a complete person in the image of dignity that he projected.” Despite the setback caused by the LIFE Magazine incident, Eckstine continued to have a successful career for another 35 years although, perhaps on account of that incident, he never became an icon like Louis Armstrong, even after having achieved a measure of enduring greatness.

***

Billy Eckstine and his Orchestra: Rhythm in a Riff:

Billy Eckstine: I Don’t Stand a Ghost of a Chance with You: