by Godfrey Onime

At the physicians’ lounge recently, a colleague asked me, “How are the new interns? Aren’t you glad another July is over?”

I told him that our new class of first-year medical residents, or interns as they are commonly called, seemed quite strong. As for his celebratory comments about the vanquishing of July, I knew what he meant. After all, a common sage in American teaching hospitals is, “Don’t get sick in July.” The reason for this sentiment is because that’s when most of the doctors are the most green, or inexperienced.

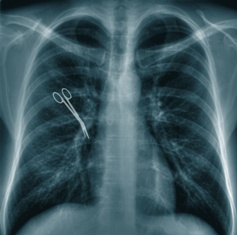

It happens that when we consider medical errors, the level of experience of a doctor or other healthcare providers — as with any profession for that matter — is quite important. Less experience often equals more mistakes – from writing to accounting to carpentry. These screwups can become learning opportunities for these professionals. But medicine is different. Often, people die.

The so-called July effect in American teaching hospitals is one example of how inexperience can come to bear in the vexing world of medical errors. For one, July 1st or thereabout is the date when fresh medical school graduates transform into new interns, ready to practice — on you. That’s when they begin to zig-zag about the hospitals at frenzied paces in their yet shinny, starched white coats and introducing themselves as Dr. Superman (or woman). To truly understand the forces at play here, let’s for a moment get into the head of the new intern. Read more »