by Jochen Szangolies

There seems to be a peculiar kind of compulsion among the philosophically minded to return, time and again, to the issue of free will. It’s like a sore on the gums of philosophy—one that might heal if only we could stop worrying it with our collective tongues. Such a wide-spread affliction surely deserves a fitting name: I propose Morsicatio Libertatum (ML), the uncontrollable urge to chew on freedom.

With the implicit irony duly appreciated, I am no exception to this rule: bouts of ML seize me, on occasion, while taking a shower, while walking through the woods, while pondering what to have for dinner. If I differ in any way from the typical afflicted, then it’s because deep down, I am not at all convinced that the issue really matters all that much. In most discussions of the problem of freedom, each camp seems so invested in their position that they consider a contravening argument not just erroneous, but nearly a point of moral offense. But ultimately, wherever the chips may fall, we can do nothing but live our lives as we do: whether by fate’s preordainment or by our own choices.

After all, it’s not like we consider things only worthwhile if their completion is, in some sense, up to us: the last chapter of the novel you’re reading, the last scene of the film you’re watching was completed long before you ever turned the first page or switched on the TV. Yet, there may be considerable enjoyment in witnessing its unfolding. Even more obviously, the tracks the rollercoaster rides are right there, for you to see—but that doesn’t take away the thrill.

But still, my aim here is not to examine the psychology of arguing over free will (as rewarding a topic as that might prove). Rather, I am writing due to a particularly fierce recent bout of ML, brought on by finding myself suspended 100m above the ground, climbing through the steel trusses of Germany’s highest railway bridge, and wondering whether I’d gotten myself into this, of if I could blame the boundary conditions of the universe. Thus, perhaps this essay should best be considered therapeutic (then again, perhaps that’s true of all philosophy).

The basic root of the problem of freedom, as I see it, is the apparent mismatch between two stories about the world: the one told by our experience, and the one told by our scientific investigations. Suppose I have a choice between two options, A and B—as in, literally writing the letters ‘A’ and ‘B’ right now. I choose: B. It seems to me nearly unquestionably the case that I could have, equally well, chosen A—all else being equal, my choice seems to have been open to me, and nothing else.

Yet, this is difficult to square with the image of a world governed by incontrovertible scientific laws. This is most usually phrased in the form of the Consequence Argument (CA), most explicitly formulated by the philosopher Peter van Inwagen. Put simply:

The past isn’t up to me

The laws of physics aren’t up to me

The past and the laws uniquely determine the future

Hence, the future isn’t up to me

(For an illuminating take on this ‘pretty good’ argument, see apparent fellow ML-sufferer Charlie Huenemann’s discussion in these very pages.)

The argument is clearly valid—given the truth of its premises, the conclusion is certain. Thus, if we want for there to be an active role for us in shaping the future, in some small ways at least, its premises are where we must focus our efforts.

Consequences And Ways The World Might Be

The CA encapsulates a particular metaphysical commitment—to a material, physical world, governed by strict laws. This view often tacitly underlies modern discussions of the free will question. Consider, for instance, the take on the issue by physicist and science communicator Sabine Hossenfelder:

[The] laws have the common property that if you have an initial condition at one moment in time, for example the exact details of the particles in your brain and all your brain’s inputs, then you can calculate what happens at any other moment in time from those initial conditions. […] These deterministic laws of nature apply to you and your brain because you are made of particles, and what happens with you is a consequence of what happens with those particles.

This is what might be called the ‘prescriptivist’ view of physical laws: whatever happens, happens the particular way it does because the physical laws decree it to be thus. This view is common among physicists; Sean Carrol, in The Big Picture, echoing a point of Bertrand Russell, argues that natural laws, such as the conservation of momentum, have effectively excised the troublesome notion of ‘cause’ from physics:

So Aristotle observes a world populated by countless changing things, and infers a cause in each case. A is caused to move by B, which in turn is caused to move by C, and so on. It’s reasonable to ask: What started it all? […] Once we know about conservation of momentum, that idea loses its steam. […] [T]he new physics of Galileo and his friends implied an entirely new ontology, a deep shift in how we thought about the nature of reality. “Causes” didn’t have the central role that they once did. The universe doesn’t need a push; it can just keep going.

With an appeal to natural laws, the troublesome chain of causality, and the ‘prime mover’ it seems to necessitate, is ‘cast into the flames’ as just so much sophistry and illusion. But such an appeal introduces an incendiary problem all of its own: in the words of late, great cosmologist Stephen Hawking, ‘What is it that breathes fire into the equations and makes a universe for them to describe?’.

Hawking himself was a firm believer in the primacy of natural law, as emphasized by another famous quotation of his: ‘Because there is a law such as gravity, the Universe can and will create itself from nothing’—referring to the fact that gravitational potential energy, being negative, can offset the energy of the rest of the universe for a total net energy of zero. The law comes first: then the universe.

But his choice of words in the first quotation suggests a different attitude towards the laws of physics: rather than prescriptive, governing what happens, they may be thought of as descriptive, merely giving a sufficiently succinct account of what happens. Thus, rather than excising cause from the physical world in favor of law, we may instead regard law as just forming a succinct description of how events cause one another—leading to two distinct possible ways the world might be: the Hawkingverse, governed by laws sufficiently immolated, and the Aristocosm, where laws just describe what happens by causal mediation.

Neither, however, will help us with the Consequence Argument: in the Aristocosm, we merely need to replace ‘laws’ by ‘causality’, and the argument’s force is preserved. However, each of these universes suffers from its own issues: in a causal universe, there arises the question of what got things going in the first place, and what it is about A such that it necessitates the occurrence of B; a world governed by law needs to explain how laws—formal, immaterial objects—actually make stuff happen. But we are now in a position to vary some of the initial assumptions entering into the argument, and observing the effect.

So let’s first start with another common variation that is often introduced, which—on the most straightforward reading—will, however, also be found to be unhelpful. This is Chanceworld, where strict rule of law (or causality) is, at least occasionally, replaced by random chance. But the CA is easily patched up in this case: the outcome of chance events isn’t any more up to me than those determined by fixed laws. So does Chanceworld, at least, improve upon the prior options in terms of its grounding? At first sight, it might seem so: the world got going by a random chance event, and from there on, causality took over, for the most part, occasionally helped out by throwing a coin for difficult decisions, perhaps.

But in fact, the problem persists: there is no accounting of how a chance event decides between different options. Chance choice is a black box that somehow makes A happen, rather than B—if we accept this, we essentially accept that how things happen is a mystery. We might well be willing to do so, but we should recognize that this doesn’t leave us in a better position than the previous options did—we could have just as well accepted that the laws of physics are ‘just so’, and that a causal chain got going somehow. Mystery is well and good, but we should not pretend that the mere familiarity of the concepts imbues them with any greater claim to respectability than alternative options.

This is indeed what I suppose happens in many of these discussions: we don’t question chance, causality, or natural law, because we have been so exposed to them that we’re willing to accept them as ‘primitive notions’—able to figure in explanations, but not in need of explanation themselves. They are what I like to call soporific explanantia—they serve little purpose but to put our doubts to sleep, as in the story where in lieu of an explanation for opium’s sleep-inducing powers a reference to its ‘soporific qualities’ is offered.

Sometimes it is alleged that science tells us of the reality of natural laws. But science tells us nothing of the sort. What we have empirical grounds to believe is the existence of stable regularities; natural laws are inductive generalizations, and thus, on these grounds alone always hypothetical (we can’t observe the totality of events to ensure that a law has the universal validity we assume it to have).

Recognizing this, we arrive at the Humeyverse, a world that is nothing but a quilt-like patchwork of events, somewhat fashioned after philosopher David Lewis’ Humeanism. Such a world, if it is not totally random, would still show a certain regularity—that is, it could be reduced to some set of data smaller than a full description of every event, and rules to extract the full ‘quilt’ of the world from that: initial conditions and laws of physics. The laws of physics here have a strongly descriptive character, merely summarizing the regularities in the pattern of events—if that pattern were different, so would the laws be.

The idea that a universe could essentially be nothing but a patchwork of events, and yet exhibit some regularity, might seem strange. But information theorist and AI pioneer Jürgen Schmidhuber has developed the notion of ‘algorithmic theories of everything’, where every event is drawn from a certain probability distribution obeying a requirement of formal describability—which is enough to ensure that overwhelmingly most of the worlds generated in this way are highly regular.

In the Humeyverse, then, premise 2 of the CA does not necessarily hold: if, in accordance with physical laws P I choose A, my choosing B would simply mean that some different laws P’ must hold. Hence, on a descriptivist understanding of physical laws, there is, in principle, an ‘open spot’ for genuine choice. More importantly, it isn’t necessarily the case that the laws of physics are impacted at every event where I make a choice—for there to be genuine freedom, we only need to stipulate that I could have chosen B; I need not, in fact, have done so. My free choice of A is just as free, even if it happens to align with the laws P. Hence, and that’s the moral of the Humeyverse, even fixed laws need not be in conflict with freedom.

To see this more clearly, let’s take a look at another possible world, the Occasionalism of French Cartesian philosopher and Oratorian priest Nicolas Malebranche. On this view, at each instant, God chooses the next state of the world, in a process of continuous creation. In doing so, God observes a principle of ‘order’, which underlies what we consider to be natural law. But, like a painter who could place their next brush-stroke anywhere on the canvas, but chooses a spot fitting the composition, God is ultimately free. Such a world would contain all the observed regularities we elevate to natural laws to underwrite the Consequence Argument, yet without threatening freedom—God’s, at least.

God’s freedom might be of little use to us, however, and (potentially) changing the laws of physics whenever I choose to poach rather than scramble my breakfast egg might seem a little severe. But with the notions developed so far, we may have another crack at a notion we have already discarded: chance, we stipulated, is of no help in securing us influence over the future, because we have no influence over chance. But this is, essentially, a ‘prescriptivist’ notion of indeterminism: whenever the physical laws leave some choice open, a random ‘black box’ process intervenes to fill in the gap, and make the choice.

We might, now, rather appeal to a ‘descriptivist’ reading: the physical laws, on occasion, leave some ‘elbow room’—not uniquely determining a single possible way for the future to be, but leaving open alternatives. Rather than stipulating that some chance selection fill in the gap, we might then propose that it is our free choice that steps in—thus yielding a kind of ‘micro-occasionalism’. Call this, then, the Openverse. But do we have free will in the Openverse? After all, the laws of physics are such that, even if they don’t uniquely dictate an outcome, they typically give probabilities for each option. Are we free if we are required to act with a certain frequency in a certain way, even in the limit?

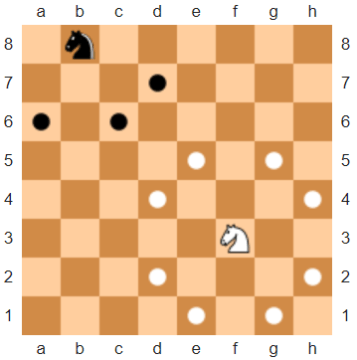

Consider, by way of analogy, a chess player deliberating the next move. The rules of the game determine which moves are possible, and which are forbidden. But at any given point, certain moves are better than others—thus, the player, some basic competence assumed, will choose those with a higher likelihood. Nevertheless, any option remains on the table, until the actual move is made. Hence, the fact that we can make statistical judgments about outcomes does not entail constraints on the freedom of a given actor.

In the Openverse, we are free to make use of the elbow room provided by indeterministic laws of physics to have our choices matter for determining the future: the Consequence Argument doesn’t threaten our agency here. Importantly, this does not mean that the world must necessarily be this particular way for the CA to fail: by exhibiting a consistent setting where it does not apply, the argument is shown to be unsound—because it is possible for the world to be such that the conclusion of the CA is avoided, it doesn’t hold, even if the world should be otherwise.

The Incoherence Argument

All of this will have little impact on those believing in the impossibility of free will, and justifiably so. The Consequence Argument, after all, isn’t the only one threatening our liberty to act—and indeed, isn’t the strongest one, either. While it is usually the first argument proposed, if pressed, its proponents often retreat to shelter behind the walls of what might be called the Incoherence Argument: it isn’t that the notion of free will is contradicted by the way the world happens to be, it’s that the notion itself is contradictory. In the formulation of Hossenfelder:

The reason this idea of free will turns out to be incompatible with the laws of nature is that it never made sense in the first place. You see, that thing you call “free will” should in some sense allow you to choose what you want. But then it’s either determined by what you want, in which case it’s not free, or it’s not determined, in which case it’s not a will.

Free will, it’s alleged, is an exercise in wanting to have your cake, and eat it, too. If your will is definite, something ought to have made it thus, and hence, it’s that which is the reason for your action; if it’s not, then we’re back with random chance. As Schopenhauer put it, ‘a man can do as he wills, but not will as he wills.’

We may want to reject this, proposing to have the will determine itself. But then, it seems we become trapped in infinite regress. If we willed2 our will1 to be a particular way, then our will2 to do so must itself be willed3 to be such as to will2 our will1 to be that way, and so on.

The concept of free will, then, seems to be unfounded. But to this charge, we can simply reply: tu quoque! Every proposed means for the events of the world to unfold ultimately hides a question mark, a point beyond which explanation can’t proceed. The regress we enter with the willing of the will is just the regress of causes the Aristocosm entails. It is the fire that needs to be breathed into the natural laws governing the Hawkingverse. The black box that decides the course of the future in Chanceworld. God’s choice in Malebranchian Occasionalism. The origin of the patchwork of events in the Humeyverse.

The Incoherence Argument shows that we can’t give an account of how will could actually work—true. But so it is for every proposed explanation of how stuff happens. The believer in free will is, then, at least not any worse off than the believer in causality, or (prescriptive) natural laws, or chance. We’re simply more used to accepting these concepts; but we should not allow their soporific quality to lull us to sleep: the mystery remains.

(In the end, I suspect this mystery is simply an artifact of an intrinsic insufficiency of our mode of explanation; but on this, more next time.)