by Omar Baig

On October 23rd 2020, The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum reopened their flagship, Frank Lloyd Wright designed building on NYC’s iconic Museum Mile at 25% capacity and expanded to 50% by April 27th, 2021. Associate Curator, Ashley James selected pieces from Guggenheim’s permanent collection: by 13 contemporary artists, like Carrie Mae Weems, Carlos Motto, and Sable Elyse Smith, for Off The Record (Apr 2—Sept 27, 2021). This exhibition investigates “the power dynamics obscured by official documentation” and playfully resists the so-called objectivity of official records that preserve “truth” by what remains excluded or “off” the record. Off The Record marks James’ first group exhibition since guest curating Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power (Sept 14–Feb 3, 2019) for the Brooklyn Museum.

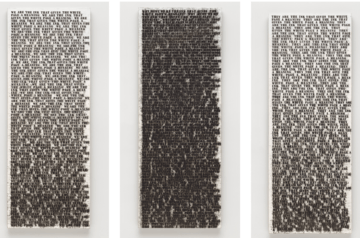

Unlike her previous exhibit, James chose not to explicitly market Off The Record as a collection show of African American (or female) artists; despite 9 out of its 13 artists identifying as Black (and 10 as women). Glenn Ligon’s Prisoner of Love #1-3 (1991) series, in particular, epitomizes Off The Record’s point of view on race: by repeatedly stenciling the binary statement “We are the ink that gives the white page a meaning.” French writer Jean Genet’s Prisoner of Love (1986) introduced the phrase, which Ligon adapted and increasingly overlapped across three, 6.5 by 2.5 feet, linen canvases. The black text on white-canvas, its wall text states, “serve as a clear, though not an exclusive, reference to race and other constructs; yet the blurring of the words effectively relieves these polarities of their impact.”

Unlike her previous exhibit, James chose not to explicitly market Off The Record as a collection show of African American (or female) artists; despite 9 out of its 13 artists identifying as Black (and 10 as women). Glenn Ligon’s Prisoner of Love #1-3 (1991) series, in particular, epitomizes Off The Record’s point of view on race: by repeatedly stenciling the binary statement “We are the ink that gives the white page a meaning.” French writer Jean Genet’s Prisoner of Love (1986) introduced the phrase, which Ligon adapted and increasingly overlapped across three, 6.5 by 2.5 feet, linen canvases. The black text on white-canvas, its wall text states, “serve as a clear, though not an exclusive, reference to race and other constructs; yet the blurring of the words effectively relieves these polarities of their impact.”

In our interview, James clarifies, “The idea of not having an exclusively Black show wasn’t a decision I made deliberately: it stemmed from seeing that the artworks in the collection (and I think in [the] larger art world) carries out the show’s thesis—which necessarily means not only Black artists.” Exclusively marketing this show as Black, however, would have prevented James from including works by artistic and intellectual heroes, like conceptual artist and Neo-Kantian philosopher, Adrian Piper. In 2012, for example, Piper publicly announced her retirement from exclusively African American group shows. Piper’s work is particularly apt, given her varied interests in record keeping: from her research archive and foundation in Berlin; to her presence on third party records, quietly collected from public and governmental institutions (like finding her name on a TSA suspicious travelers list).

African American Record Keeping

Sadie Barnette’s five inkjet prints from My Father’s FBI File; Government Employees Installation (2017), which the Guggenheim acquired in 2019, served as the initial inspiration for James’ current exhibit. In 2016, the US awarded Barnette’s family access to 500 pages of FBI records, after they filed a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request. These records revealed the FBI’s decades-long surveillance of her father, Rodney Barnette and his membership with the Black Panthers. From 1959 to 1971, the FBI’s COINTELPRO program aimed to infiltrate and disrupt subversive, domestic political and revolutionary groups like feminists, Communists, anti-Vietnam leaders, and civil rights activists. The FBI threatened and harassed civil rights leaders like Martin Luther King Jr., infiltrated groups like The Nation of Islam, and “neutralized” Black Panther leaders like Fred Hampton, Zayd Shakur, and Mumia Abu-Jamal.

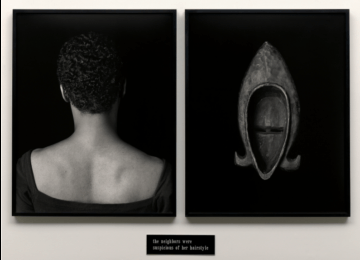

The FBI targeted, spied on, and “hunted down” these leaders by illegally arresting, prosecuting, and subjecting to evidence or witness tampering and perjury. In a similar vein, Lorna Simpson’s Flipside (1991) “alludes to the everyday surveillance that people of the Black diaspora endure.” This diptych of two Gelatin silver prints juxtaposes a black and white photographic portrait of an African American woman with a closely cropped afro, next to an unidentified African mask. Under both images, an engraved plaque reads: “the neighbors were suspicious of her hairstyle.” Whereas, Leslie Hewitt’s Riffs on Real Time 3, 6, and 10 (2006-09) personal records, photos, and other paper-based materials from the Black magazines like Ebony and Jet offers “a discursive meditation on memory, history, and beauty at the intersection of the personal, the political, the public, and the obscure.”

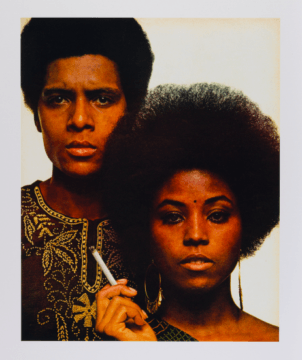

Hank Willis Thomas’ three pieces from Unbranded: Reflections in Black by Corporate America 1968–2008 (2005–08), appropriate ads from print magazines, published in 1971, 1975, and 1984. “By removing all text, including product names, the overlaid slogans and marketing copy,” its wall-text notes, “Thomas illuminates the visual ways in which the corporate marketplace targeted a growing Black middle class in the years following the civil rights movement.” These images of natural afros and unprocessed hair, along with attractive Black models and celebrities in luxury clothes and jewelry, James continues, “read as attempts to pander in the wake of the Black Is Beautiful movement”. Whereas the more anti-consumerist Black Panthers aimed at dismantling the late-stage capitalist and legal structures.

Lastly, Carrie Mae Weems’ “You Became Mammie, Mama, Mother & Then, Yes, Confidant—Ha” and “Descending the Throne You Became Foot Soldier & Cook” are two chromogenic prints with etched text on glass; taken from her series, From Here I Saw What Happened And I Cried (1995–96), which appropriated daguerreotypes of enslaved Africans: named Drana, Jack, Renty, and Delia. The university originally commissioned Swiss naturalist and Harvard professor Louis Agassiz, in 1850, to take these photographic portraits. Agassiz used these as evidence of “physiogamatic types,” or body differences, that supported his racist theories on Black inferiority. Weems cropped, tinted, and enlarged these images from Harvard’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology without permission, despite signing a contract that said she wouldn’t.

Harvard, in response, threatened to sue for copyright infringement and breach of contract. “I think that your suing me would be a really good thing,” Weems told university officials, “You should. And we should have this conversation in court.” Harvard, however, was not ready to open up this conversation on the moral impropriety of them owning and profiting from the daguerreotypes of enslaved subjects. Instead, both parties agreed that Harvard would receive a portion of the sales from From Here I Saw: of which they then bought a number of its pieces for their private collection. After two decades, our court system can now finally address White privilege, which stems from the legal and historical ownership of slaves; but is due for a legal precedent that will finally uphold their descendants’ right to reclaim their ancestor’s inheritance.

On March 4th, 2021, the Superior Court Judge to Middlesex County, Camille Sharrouf, Jr., dismissed Connecticut resident Tamara Lanier’s lawsuit against Harvard over their ownership of her enslaved relatives’ images. Judge Sharrouf sided with Harvard, on the grounds that Lanier both missed the statute of limitations to contest its ownership and lacks traditional property rights over images commissioned and preserved by Harvard: regardless of the coerced origins of their enslaved subjects. “Unfortunately,” Judge Sharrouf added, “this Court is constrained by current legal principles, […in determining] whether or not to recognize causes of action and to provide the redress Lanier now seeks.” Given the lack of relevant case law, Lanier’s legal team intends to appeal this decision to the Massachusetts Supreme Court, where they expect a more favorable, landmark ruling.

Record Keeping in Other Contexts

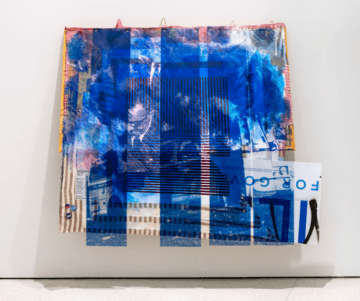

Tomashi Jackson’s Ecology of Fear (Gillum for Governor of Florida)(Freedom Riders bus bombed by KKK) (2020) is the most recent artwork in Off The Record. Jackson “collapsed” and overlaid images of Lyndon B. Johnson signing the 1965 Voting Rights Act, onto Theodore Gaffney’s iconic photo of the Freedom Rider bus bombing, taken for Jet magazine in 1961. Ecology melds Pentelic marble dust from the ruins of Ancient Greece’s most prominent civic institutions, like the Parthenon–which Jackson calls democracy’s “rubble of origin”–along with voting records, like Greek’s recent ballots. Materials like Andrew Gillium’s campaign sign, from his failed 2018 run for Florida’s governor, brings Ecology’s meditation on democracy full circle: as its 3D collage and installation juts out like an awning that hangs at 7.5 x 8.3 x 1 ft.

Ecology presents, on its face, more as an abstract painting, compared to the more figurative types of appropriation featured by Off The Record. Unlike the previous works discussed, Ecology not only highlights record keeping particular to the Civil Rights movement but also expands upon democratic record keeping: in foreign, anthropological, and national contexts. In a similar vein, Carlos Motta’s Brief History of US Interventions in Latin America Since 1946 (2005/2014) presents over 20 brief accounts of US intervention in South American national politics from 1946 to 2014–likely inspired by the post-9/11 invasion of Afghanistan and Iraq. The Guggenheim reprinted copies of Brief History on a sheet of newspaper, which they folded in fourths and gave freely to visitors.

Ecology presents, on its face, more as an abstract painting, compared to the more figurative types of appropriation featured by Off The Record. Unlike the previous works discussed, Ecology not only highlights record keeping particular to the Civil Rights movement but also expands upon democratic record keeping: in foreign, anthropological, and national contexts. In a similar vein, Carlos Motta’s Brief History of US Interventions in Latin America Since 1946 (2005/2014) presents over 20 brief accounts of US intervention in South American national politics from 1946 to 2014–likely inspired by the post-9/11 invasion of Afghanistan and Iraq. The Guggenheim reprinted copies of Brief History on a sheet of newspaper, which they folded in fourths and gave freely to visitors.

Sarah Charlesworth’s Herald Tribune: November 1977 is the oldest piece shown in Off The Record and is an example from one of the Pictures Generation’s members: as “a group of artists who interrogated how the media is implicated in the formation of history and even meaning itself.” Charlesworth masks the text from the front page of the Herald Tribune, leaving only its images and masthead. These redactions, its wall text states, “makes the paper’s underlying ideologies that much clearer.” Oppenheim’s Killed Negatives, After Walker Evans (2006) are chromogenic prints of Walker Evans’ “killed negatives” from the Farm Security Administration’s archive, which commissioned him to document the Great Depression. Evans punched a hole through these negatives to prevent their future publication, which Oppenheim reprinted (holes and all) in 2007, through her own photographic interventions and re-stagings.

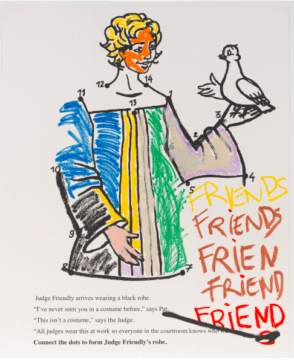

Sable Elyse Smith’s Coloring Book 9 and 18 (2018) are two silkscreen reproductions from an actual children’s coloring book on the US justice system that “serve to teach children the logics of incarceration from a young age.” One page introduces Judge Friendly and clarifies that her black robe is not a costume, but something all judges wear at work so everyone “knows who we are.” Another page depicts families waiting outside of a courtroom and instructs that “everyone brings something to read” or quietly work on, like a puzzle. Sarah Cwynar’s Bananas, Acropolis, and Bardot, from her Encyclopedia Grid (2014) series, are perhaps the most meta critique of record keeping in Off The Record. In all three works, Cwynar organizes images into a grid-like collection, related to the subject of each series: as their finger stages its own interventions by inserting itself into the photographic subject of research.

Sable Elyse Smith’s Coloring Book 9 and 18 (2018) are two silkscreen reproductions from an actual children’s coloring book on the US justice system that “serve to teach children the logics of incarceration from a young age.” One page introduces Judge Friendly and clarifies that her black robe is not a costume, but something all judges wear at work so everyone “knows who we are.” Another page depicts families waiting outside of a courtroom and instructs that “everyone brings something to read” or quietly work on, like a puzzle. Sarah Cwynar’s Bananas, Acropolis, and Bardot, from her Encyclopedia Grid (2014) series, are perhaps the most meta critique of record keeping in Off The Record. In all three works, Cwynar organizes images into a grid-like collection, related to the subject of each series: as their finger stages its own interventions by inserting itself into the photographic subject of research.

These artists illustrate Off The Record’s potential to expand and reflect the greater scope of record keeping, if given the opportunity to travel to other museums and include work from other artists and collections. This, James tells me, is her hope for Off The Record, which in her mind, highlights “all of the artists [who] take some kind of revisionary stance vis-a-vis historical records—to different, and yes, their own singular ends—which is something that black artists are invested in, but so too artists of other races who recognize the bias and constructedness of records and record-keeping.” Each of these art works, I joke, are like their own deconstructive act: of supposedly official records that are singular and primary sources of objectivity, which reveal a multiplicity of logics involved in each form of record keeping.

Record-Keeping as Meta-institutional Critique?

The Guggenheim concurrently displays Off The Record with the solo exhibition, The Hugo Boss Prize 2020: Deana Lawson, Centropy (May 7—Oct 11, 2021). Five outside curators, including Naomi Beckwith, selected Deana Lawson as the annual winner of their 2020 Hugo Boss Prize. Full-time curators, Ashley James and Katherine Brinson then organized Centropy. The Guggenheim subsequently hired Beckwith as their first Black Deputy Director, on Jan 28, 2021: following their decision to hire James as their first, full-time curator of African American descent (in Nov 2019). James was not the first African American, however, hired by the Guggenheim to curate their own major exhibit. That distinction belongs to Chaédria LaBouvier, who the Guggenheim contractually hired the year before, as their first curator of African American (or Cuban) descent.

Aside from Nigerian co-curator Okwui Enwezor, LaBouvier was the first African American curator of her kind to organize their own exhibit at the Guggenheim and to write their own exhibition catalog. Shortly after the premiere, for Basquiat’s “Defacement”: The Untold Story (June 21–Nov 6, 2019) LaBouvier spoke out against the leadership team: including Richard Armstrong (Director), Nancy Spector (then Deputy Director and Chief Curator), and Elizabeth Duggal (COO, and now Deputy Director). Nancy Spector, in particular, did not invite LaBouvier to speak at a panel discussion for the very exhibit she curated. In response, LaBouvier showed up in the audience to express her frustration and posted her criticisms of the leadership team on Twitter: which went viral after describing their interactions with them as “the most racist professional experience of [her] life.”

These members, LaBouvier alleges, maliciously undermined and erased her contributions as Defacement’s lead curator. This falling out, however, was not limited to LaBouvier’s experience with Guggenheim’s leadership: generating numerous, and at times contradictory, forms of institutional record keeping. These alternative records not only include LaBouvier’s viral Twitter threads or statements made to the press, but the unauthorized records produced by 169 current and former employees that drafted, signed, and submitted an open letter to the Board of Trustees, on June 29. The letter criticized Armstrong’s handling of LaBouvier’s complaints, and accused him of making racially insensitive comments towards both staff and featured artists. In response, the Board hired Kramer Levin LLC, as an outside law firm, to “independently” gather and review 15000 pages of internal documents, interviews, and employee surveys.

After acquitting the very leadership that hired them three months ago of any wrongdoing, Kramer Levin has unsurprisingly refused to release any of the materials of, or data from, their investigation or final reports. As their internal inquiry unfolded, a number of these signatories anonymously formed A Better Guggenheim–uploading leaked internal documents, audio recordings and transcripts, internal meeting minutes, and allegations of racist and sexist microaggressions towards employees on their website–and providing resources for furloughed museum staff affected by the pandemic and their allies. The pandemic also disrupted contract negotiations between Guggenheim’s 22 full-time employees and 145 on-call staff: which joined workers at MoMa PS1, in June 2019, by voting to unionize with the International Union of Operating Engineers (IUOE) Local 30.

Correcting The Record: Towards Unionization

Chaédria LaBouvier’s experience as the first African American and/or Cuban curator illustrates how the leadership team at major public art institutions like the Guggenheim can erase their employees’ contributions by controlling the narrative around their public and internal record. LaBouvier alleged that members like Nancy Spector tried to prevent her from receiving full credit for her research contributions to the catalog for Basquiat’s Defacement. Spector and Armstrong, LaBouvier also alleged, quietly prevented her from giving guided tours for VIP visitors or attending the official panel for her own exhibit as a speaker. LaBouvier also claimed their press department neither adequately promoted her exhibit nor connected not her with journalists that reached out to the Guggenheim for an interview.

These miscommunications were attributable, in part, to LaBouvier’s unprecedented role as a contracted curator at the Guggenheim: whose leadership, at time, neither clarified the expected job duties of part-time and contracted curators, nor formalized the internal and external channels that could fairly and transparently field press inquiries, tour requests, and participation in official events related to their exhibit. In turn, current and former staff have taken it upon themselves to go “off the record” and anonymously upload their internal documents in support of both LaBouvier and the staff fired after the start of the pandemic. This begs two questions: (1) how can public art museums make more transparent and equitable administrative decisions and (2) what can employers do to ensure their own record keeping? The answers will likely involve collective bargaining, unionization, and contract negotiations.

On Feb 16, 2021, the IUOE signed a three-year collective bargaining agreement with the Guggenheim: which “won an average wage increase of 10%, bonuses, premium-free health insurance for families, transparent scheduling practices, safety improvements, and dignity.” The Whitney Museum also unionized this May, after being inspired by the New Museum’s fellow NYC-based staff and their recent success in unionizing. Both follow in MoMa’s footsteps, by joining UAW Local 2110 union for technical, professional, and office workers. In 1971, MoMa became the country’s first art museum to unionize: which, for fifty years, was one of North America’s few unionized public and cultural institutions of fine art. In response to the pandemic, however, an unprecedented 20 US museum staff have “unionized in the last year or are trying to form unions.”

In April 2021, the American Alliance of Museums released a survey of “2,600 current and former museum employees, consultants, volunteers, and students” that found 43% of US museum staff lost income due to the pandemic: with 9% laid off and 5% still unemployed. “Since we unionised at the New Museum,” Dana Kopel recounts, “workers at other museums across the United States have formed their own unions: at the Tenement Museum in New York, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, the Milwaukee Art Museum, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, to name only a few.” Kopel notes that while museums shrunk staff and hemorrhaged ticket sales during the pandemic, some of their investment portfolios grew by as much as 40%. Further unionization of public art museums may help staff reinvest some of these record gains back into their salaries, benefits, and training opportunities.