by Rafaël Newman

…the historical sense involves a perception, not only of the pastness of the past, but of its presence…This historical sense, which is a sense of the timeless as well as of the temporal and of the timeless and of the temporal together, is what makes a writer traditional. And it is at the same time what makes a writer most acutely conscious of his place in time, of his own contemporaneity.

T.S. Eliot, “Tradition and the Individual Talent”

For Asa Weinstein, on his birthday

On August 17, 1977, I stopped in as usual at our neighbors’ house, to while away the summer day with my younger brother and sister until our mother’s return home from the university. Our friends – two sets of twins and one singleton – were home-schooled by their mother, and we were all having a summer staycation in any case, so there was always somebody at their house, and a reliably lively time to be had. What met me when I walked into the kitchen that morning, however, was an unaccustomed stillness. All five young people were hovering around the door to the living room while their mother sat at the kitchen table, hunched over a newspaper. “Elvis is dead,” whispered the singleton. Presley had died the day before, in Memphis, in the early afternoon of August 16; but the headlines, and President Carter’s address, would be that day’s news, on the outskirts of Vancouver as elsewhere around the world.

On August 17, 1977, I stopped in as usual at our neighbors’ house, to while away the summer day with my younger brother and sister until our mother’s return home from the university. Our friends – two sets of twins and one singleton – were home-schooled by their mother, and we were all having a summer staycation in any case, so there was always somebody at their house, and a reliably lively time to be had. What met me when I walked into the kitchen that morning, however, was an unaccustomed stillness. All five young people were hovering around the door to the living room while their mother sat at the kitchen table, hunched over a newspaper. “Elvis is dead,” whispered the singleton. Presley had died the day before, in Memphis, in the early afternoon of August 16; but the headlines, and President Carter’s address, would be that day’s news, on the outskirts of Vancouver as elsewhere around the world.

I was thirteen years old and freshly returned from an ersatz bar mitzvah trip to Israel with my professor father. My psychologist mother’s musical taste – and thus mine, for the moment – ran to Mozart and The Beatles, with admixtures of Joni Mitchell and bel canto. Elvis was a yokel and a hillbilly, I had been given to understand at home: a pioneer of perfidiously whitewashed Black culture and a bridgehead of American imperialism on a Canadian West Coast swarming with counterculture “draft dodgers”. So on that day, in that mourning household, in an access of hubris and pubescent provocation, I made a disrespectful remark; in fact, I may have done nothing more than clutch my brow melodramatically and feign a heartbroken sigh.

“Get the fuck out of my house.”

Our friends’ mother, a Pennsylvanian expat as renowned for her discipline as for her volubility and salty vocabulary, had raised her baleful head to deliver my sentence of temporary exile. Her eyes were red; she had clearly been weeping. The mixture of grief and anger was palpable, alienating, and uncanny: I was still young enough to be shocked by the spectacle of a mother’s tears. Something epochal had obviously occurred, to so shake the foundations of parental placidity. I had clearly misjudged the significance of Elvis Presley.

It wasn’t until the following year, when we moved from the hippie and/or heavy metal culture of suburban British Columbia to edgier, Anglophile, big-city Toronto, that I understood the meaning of Elvis’s death, as epistemically shattering for the Boomer generation (to which I theoretically belonged, my birth year falling at the very tail end of the period) as Kennedy’s had been for the previous cohort, and as John Lennon’s would be for mine, in a couple of years. In a friend’s basement rec room in Rosedale, a posh Toronto neighborhood whose youngsters could afford imported British vinyl, I listened in awe to “1977”, the B-side of “White Riot”, the first ever single by The Clash, from their eponymously titled debut album released the year before:

In 1977

I hope I go to heaven

I been too long on the dole

And I can’t work at all

Danger stranger

You better paint your face

No Elvis, Beatles or The Rolling Stones

In 1977

Knives in West 11

Ain’t so lucky to be rich

Sten-guns in Knightsbridge

Danger stranger

You better paint your face

No Elvis, Beatles or The Rolling Stones

The song had been written and released before Elvis died, so its declaration of the end of the traditional Rock ‘n Roll era was prescient: if Presley wasn’t actually dead yet, he was already as depleted a signifier as The Beatles, who had long since broken up, and The Stones, who at the time of this writing are of course still active in some form, but whose relevance in 1977, according to The Clash, was already on the wane, in an era in which mock southern honky-tonk ballads were no more adequate a response than The King of Rock ‘n Roll or the Fab Four to the malaise of the modern.

Or rather, of the postmodern. In a brand-new book, a Swiss intellectual historian argues that 1977 saw the inception of our present era: the end of Grand Narratives and hopeful collective action and the birth of the individualist turn, rooted in human rights, that would eventually issue in the “identity politics” currently dividing progressive forces.*

The Clash were an unlikely herald of such an epoch, given their outspokenly activist, indeed utopian political commitments, inchoate on their first album but rapidly taking on frank form over the course of their brief existence. The sincerity of the band’s engagement risked making them self-righteous smarm merchants compared to the more bracing snark of the Sex Pistols, whose sneering, three-chord celebration of “Anarchy In The UK”, and whose cynical recognition of themselves as corporate sellouts, might have seemed better suited to an ironic age in which, as it has been defined in contrast to modernity, complicated content is wrapped in deceptively simple packages. And one in which greed would soon notoriously be declared a positive attribute.

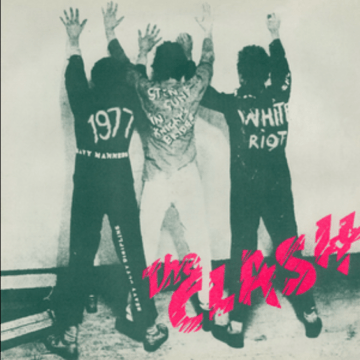

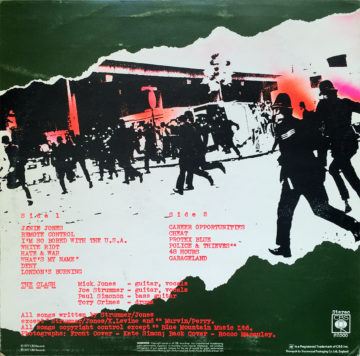

Nevertheless, in the service of their unabashedly progressive agenda, The Clash, whose name was drawn from contemporary headlines about the ongoing confrontations between police and protestors, were themselves also capable of nuance. Their first album features among its 14 tracks, virtually all DIY originals and of a regulation punk brevity (four come in under two minutes in duration), one cover, of comparatively epic length: “Police & Thieves”, their version of a reggae number released in 1976 by Junior Murvin and Lee “Scratch” Perry. At six minutes, the punk cover is actually longer than the original and established The Clash as iconoclasts on a scene that was itself iconoclastic per definitionem. Together with the debut album’s back cover art, a reworked photo of police charging demonstrators during the racially charged events at the Notting Hill Carnival in 1976, and the A-side of the single, “White Riot”, it placed the band firmly in opposition to the increasingly virulent racist, anti-immigrant rhetoric of the era. It would also make them natural headliners for the legendary Rock Against Racism concert held in Victoria Park on 30 April 1978.

Nevertheless, in the service of their unabashedly progressive agenda, The Clash, whose name was drawn from contemporary headlines about the ongoing confrontations between police and protestors, were themselves also capable of nuance. Their first album features among its 14 tracks, virtually all DIY originals and of a regulation punk brevity (four come in under two minutes in duration), one cover, of comparatively epic length: “Police & Thieves”, their version of a reggae number released in 1976 by Junior Murvin and Lee “Scratch” Perry. At six minutes, the punk cover is actually longer than the original and established The Clash as iconoclasts on a scene that was itself iconoclastic per definitionem. Together with the debut album’s back cover art, a reworked photo of police charging demonstrators during the racially charged events at the Notting Hill Carnival in 1976, and the A-side of the single, “White Riot”, it placed the band firmly in opposition to the increasingly virulent racist, anti-immigrant rhetoric of the era. It would also make them natural headliners for the legendary Rock Against Racism concert held in Victoria Park on 30 April 1978.

But “White Riot”—for my money among the few truly great punk songs, alongside “Alternative Ulster” (Stiff Little Fingers), “Orgasm Addict” (Buzzcocks), “California Über Alles” (Dead Kennedys), “I Wanna Be Sedated” (Ramones) and, yes, The Pistols’ “Anarchy In The UK”—was an unlikely anthem for an integration movement founded in a youth subculture whose ranks also uneasily included the white supremacist skinheads. It is unclear whether the song’s lyrics would be at all palatable today, in an era of ridiculed “Wiggers” and mounting sensitivity to cultural appropriation, so frank is the song’s yearning to co-opt the energy of an ethnic underclass for the rebellious purposes of the children of the establishment:

White riot – I wanna riot

White riot – a riot of my own

White riot – I wanna riot

White riot – a riot of my own

Black man gotta lot a problems

But they don’t mind throwing a brick

White people go to school

Where they teach you how to be thick

An’ everybody’s doing

Just what they’re told to

An’ nobody wants

To go to jail!

White riot – I wanna riot

White riot – a riot of my own

White riot – I wanna riot

White riot – a riot of my own

All the power’s in the hands

Of people rich enough to buy it

While we walk the street

Too chicken to even try it

Everybody’s doing

Just what they’re told to

Nobody wants

To go to jail!

As noted in a recent documentary on the 1978 RAR concert, what The Clash are doing here is not far from the spirit of the current allies of the Black Lives Matter movement: calling for solidarity, or at least a parallel demonstration of resistance, among those not marked as members of the underclass, but who can be shown to suffer from the same system that is oppressing their more visibly disadvantaged allies. The Clash read “Black” protest through a “White” lens, and thus demonstrate the possibility of re-interpreting a variety of ostensibly “ethnically” coded artifacts so as to render them capable of universal significance: such as reggae, whose apparently chilled-out vibe now reveals the menace of a tempo decelerated under a burgeoning heat; or indeed Elvis, whose libidinal energy, shocking in the 1950s, is now borrowed for the contemporary political agenda inscribed in a notably un-erotic corpus (“Janie Jones” and “Protex Blue” are among the very few Clash numbers with explicitly sexual content). The individual talent in the present thus alters the traditions of the past, without for all that discarding or entirely disavowing them.

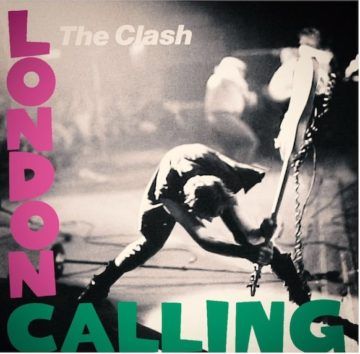

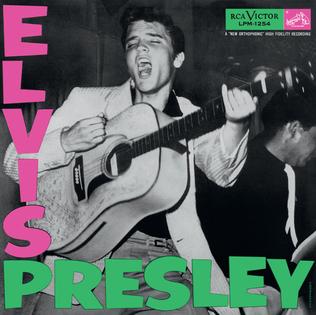

The Clash’s borrowing, perhaps even “sublation” (Oedipal murder and resurrection), of The King, whose death is prematurely announced in “1977” and whose political affiliations would have been prima facie anathema to the leftwing British outfit, is made explicit on the band’s celebrated third album, London Calling, released in 1979. Not only does it include a remarkably kickass remake of the rockabilly classic “Brand New Cadillac”, by British Elvis admirer and hip-swinger Vince Taylor; the album’s iconic cover art is also an overt reference to Presley’s 1956 eponymous first album, but inflected with a destructive gesture borrowed from The Who, themselves a link in the chain joining classic rock ‘n roll with punk. And as for The Beatles and The Stones, those other allegedly effete icons of musical modernism, The Clash raised them up as well, out of the crypt to which they had consigned them, with a devil-may-care eclecticism, entire line-up of front-men rather than one single headliner, and tendency to overflowing double (and triple) albums reminiscent of the later Liverpudlians, as well as a taste for Americana that echoed the Glimmer Twins at Muscle Shoals. The Clash were in a very real sense “post”-modern, conscious at once that they have arisen amid ruins, and intent on building something out of those fragments: using them indeed, in the words of the canonical modernist cited in my epigraph, to shore against their ruins.

The Clash’s borrowing, perhaps even “sublation” (Oedipal murder and resurrection), of The King, whose death is prematurely announced in “1977” and whose political affiliations would have been prima facie anathema to the leftwing British outfit, is made explicit on the band’s celebrated third album, London Calling, released in 1979. Not only does it include a remarkably kickass remake of the rockabilly classic “Brand New Cadillac”, by British Elvis admirer and hip-swinger Vince Taylor; the album’s iconic cover art is also an overt reference to Presley’s 1956 eponymous first album, but inflected with a destructive gesture borrowed from The Who, themselves a link in the chain joining classic rock ‘n roll with punk. And as for The Beatles and The Stones, those other allegedly effete icons of musical modernism, The Clash raised them up as well, out of the crypt to which they had consigned them, with a devil-may-care eclecticism, entire line-up of front-men rather than one single headliner, and tendency to overflowing double (and triple) albums reminiscent of the later Liverpudlians, as well as a taste for Americana that echoed the Glimmer Twins at Muscle Shoals. The Clash were in a very real sense “post”-modern, conscious at once that they have arisen amid ruins, and intent on building something out of those fragments: using them indeed, in the words of the canonical modernist cited in my epigraph, to shore against their ruins.

*

The Clash enacted post-ness in the very fabric of their songs, which were liable to feature codas, final sections of ostensibly spontaneous call-and-response recapitulations of the number’s main themes. “I’m So Bored with the USA” derisively name-checks the protagonists of two contemporary cop shows (Starsky and Kojak), while “Garageland” fleshes out the song’s micro-autobiography with a sardonic self-description: “Five guitar players, but one guitar”. The coda to “1977”, however, points forward rather than back, suddenly extending the implicit timelines into the future:

In 1977

Sod the Jubilee

In 1978

In 1979

I stayed in bed

In 1980

In 1981

The toilet don’t work

In 1982

In 1983

Here come the police

In 1984

By the time that last, fateful year rolled around, The Clash were themselves on the way to a break-up, and we have been living in a post-Clash world ever since, the poorer for a lack of the electrified protest spirit they shared with contemporary performers like Tom Robinson and Billy Bragg. Not a great deal has changed since the mid-eighties, and much has gotten worse, with new calamities preoccupying us daily. In the words of “Armagideon Time”, the cover of a 1977 reggae number by Willi Williams that The Clash, still true to their revised, if unconfessed role as mediators of subaltern culture, released in 1979 as the B-side to their apocalyptic “London Calling” single:

A lot of people won’t get no supper tonight

A lot of people won’t get no justice tonight

The battle is gettin’ hotter

In this iration

Armagideon time

A lot of people runnin’ and a hiding tonight

A lot of people won’t get no justice tonight

Remember to kick it over

No one will guide you

Armagideon time

*Philipp Sarasin, 1977: Eine kurze Geschichte der Gegenwart (Suhrkamp, 2021). An assessment follows here at a later date.