by Dick Edelstein

Following Hulu’s release of “The United States vs Billie Holiday”, the singer’s musical career has become a topic of discussion. The docu-drama is based on events in her life after she got out of prison in 1948, having served eight months on a set up drug charge. Now she was again the target of a campaign of harassment by federal agents. Narcotics boss Harry Anslinger was obsessed with stopping her from singing that damn song – Abel Meeropol’s haunting ballad “Strange Fruit”, based on his poem about the lynching of Black Americans in the South. Anslinger feared the song would stir up social unrest, and his agents promised to leave Holiday alone if she would agree to stop performing it in public. And, of course, she refused. In this particular poker game, the top cop had tipped his hand, revealing how much power Holiday must have had to be able to disturb his inner peace.

Following Hulu’s release of “The United States vs Billie Holiday”, the singer’s musical career has become a topic of discussion. The docu-drama is based on events in her life after she got out of prison in 1948, having served eight months on a set up drug charge. Now she was again the target of a campaign of harassment by federal agents. Narcotics boss Harry Anslinger was obsessed with stopping her from singing that damn song – Abel Meeropol’s haunting ballad “Strange Fruit”, based on his poem about the lynching of Black Americans in the South. Anslinger feared the song would stir up social unrest, and his agents promised to leave Holiday alone if she would agree to stop performing it in public. And, of course, she refused. In this particular poker game, the top cop had tipped his hand, revealing how much power Holiday must have had to be able to disturb his inner peace.

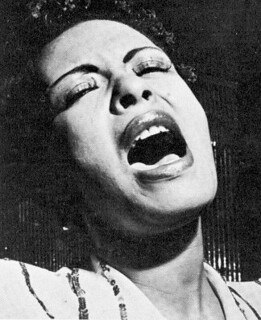

Writing in The Nation, jazz musician Ethan Iverson noted that all three films based on Holiday’s life have delighted in tawdry episodes without managing to convey the measure of her musical achievement. Hilton Als, in a review in The New Yorker, was unable to conceal his disdain for the recent biopic, observing “you won’t find much of Billie Holiday in it—and certainly not the superior intelligence of a true artist.” Both writers insist that Holiday’s memory has been short-changed in the media, and it follows that the public cannot be fully aware of her contribution to musical culture. Iverson’s thoughtful piece analyzes her many innovative contributions to musicianship and jazz vocal interpretation, while here I propose to comment on only a couple of these. But first I want to call attention to the ineffable quality of Holiday’s singing, how her delivery of lyrics and free-flowing phrasing of melody tug at the emotions. Those effects defy analysis; you have to hear Billie Holiday’s singing to know the excitement it conveys. Feeling that emotion comes easily, but describing exactly how she generates it is impossible.

My first point is a simple one: had Billie Holiday never cut a record or performed a song, her place in music history would be assured on the strength of the tunes she composed, modest in number yet important on account of their quality and popularity. Cover versions of “God Bless the Child” have been recorded hundreds of times, as a vocal number, as an instrumental, and even as a folk song, and this trend continues today as new generations find meaning in her lyrics. It’s her best-known tune and has earned a Grammy and other honors. But is it her best song? There is no good answer to that question, but if we had to choose just one song as a favorite, a number of candidates might be in the running, including “Don’t Explain”, “Fine and Mellow”, and “Lady Sings the Blues”.

On a meatier topic, musicians and critics have discussed Holiday’s role in creating a singing style that evokes the feeling of horn solos (speaking of horns in a sense that includes some woodwinds and particularly saxophones). In her early years as a performer in big bands and jazz orchestras, she stood out from the run of female vocalists, who were often seen as a novelty. They performed arranged versions of popular tunes that audiences wanted to hear, but the all-male band members frequently did not consider them serious musicians. Holiday helped change that. Her bravura performances of jazz standards displayed her musicianship and talent for interpreting lyrics. She impressed band members with her improvisational style as she ornamented and inflected melodies to suit her mood. Influenced by great horn players, she assimilated their style and emulated the effects they produced. And the sound she helped create is familiar today because she played a role in developing the performance style we identify as jazz vocal styling.

In her early years, Holiday was enchanted by the sax playing of her constant musical companion Lester Young, on whom she conferred the nickname The Prez to highlight his preeminence as the top tenor sax player of his time. The Prez was likewise struck by Holiday’s musical technique, which he studied to see what he could pick up that he might be able to incorporate into his own playing. And he named her Lady Day. Like The Prez, this sobriquet stuck for life. It is fair to say that the two young musicians, who had yet to reach the height of their fame, seriously studied each other’s musical technique and influenced one another while they worked together, first in the Basie band and later recording with pianist and band leader Teddy Wilson. Lester Young’s sweet, flowing saxophone style was one of the influences Holiday absorbed as she incorporated effects borrowed from solo horn improvisation into her vocal styling.

Billie suffered greatly, while she was growing up and later during her career, and this is the stuff in which biopics love to wallow. But they overlook an important truth when they fail to make it clear that Billie Holiday and other jazz stars became who they were despite – not because of – these travails. They often had to overcome dire circumstances stemming from racial oppression, and still they managed to triumph musically, although too often their lives were lamentably short. They achieved a measure of immortality that few of us will attain.

When I listen to Betty Carter’s sizzling, up-tempo version of “What a Little Moonlight Can Do” I’m hearing Betty Carter but I’m also hearing Billie Holiday, a musical giant who left her mark on our culture despite having to overcome massive obstacles resulting from the racial climate in the United States. Were her triumphs worth what she had to pay in the hard coin of constant trouble and strife? That depends on your point of view. I can only say that each time I hear a jazz vocal – even a brief sampled riff on a hip-hop track – I think of Lady Day.

***

Watch Billie Holiday performing “Fine and Mellow” with Coleman Hawkins, Lester Young (first two solos) and other horn soloists in a segment broadcast live on CBS television in 1957.