by David Kordahl

I’ll start this column with an over-generalization. Speaking roughly, scientific models can be classed into two categories: mechanical models, and actuarial models. Engineers and physical scientists tend to favor mechanical models, where the root causes of various effects are specified by their formalism. Predictable inputs, in such models, lead to predictable outputs. Biologists and social scientists, on the other hand, tend to favor actuarial models, which can move from measurements to inferences without positing secret causes along the way. By calling these latter models “actuarial,” I’m encouraging readers to think of the tabulations of insurance analysts, who have learned to appreciate that individuals may be unpredictable, even as they follow predictable patterns in the aggregate.

Operationally, these categories refer to different scientific practices. What I’ve called a difference between mechanical vs. actuarial models could just as well be sketched as a difference between theory-driven vs. data-driven models. Both strains have coexisted in science for the past few centuries.

Just for fun, we might attempt to caricature the history of modern science in the mechanical vs. actuarial terms introduced above. In the seventeenth century, Isaac Newton proposed a law of universal gravitation, applicable everywhere throughout the universe, which allowed naturalists to imagine that all physical effects, everywhere and for all time, were caused by physical laws, just waiting to be discovered. This view was developed to its philosophical extreme in the eighteenth century by the French mathematician, Pierre Laplace, who imagined that the universe at any particular moment implicitly contained the specifications for its entire past and future.

But in the nineteenth century, Charles Darwin introduced his theory of natural selection, which allowed naturalists to take actuarial models more seriously. Just as hidden order could cause the appearance of randomness, hidden randomness could cause the appearance of order. Read more »

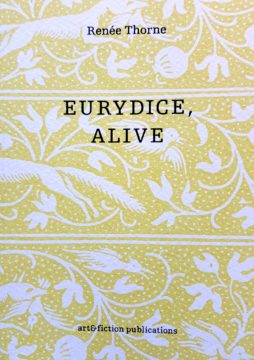

You’ve heard the story before. The poet Orpheus, celebrated for the enchanting quality of his voice, is grieving the sudden death of his young wife Eurydice. In his despair he resolves to harrow the Underworld, where he so impresses the god Hades with his singing that he is permitted to retrieve the shade of his bride and return with her, newly embodied, into the light—on one condition: that he not look back at Eurydice until they have attained the realm of the living. All is proceeding according to plan, and the pair have nearly made it to the world above, when Orpheus, overcome by the suspicion that he has been swindled, turns to assure himself that his silent wife is still following him—only to see her flee away, this time forever, back into the shadows.

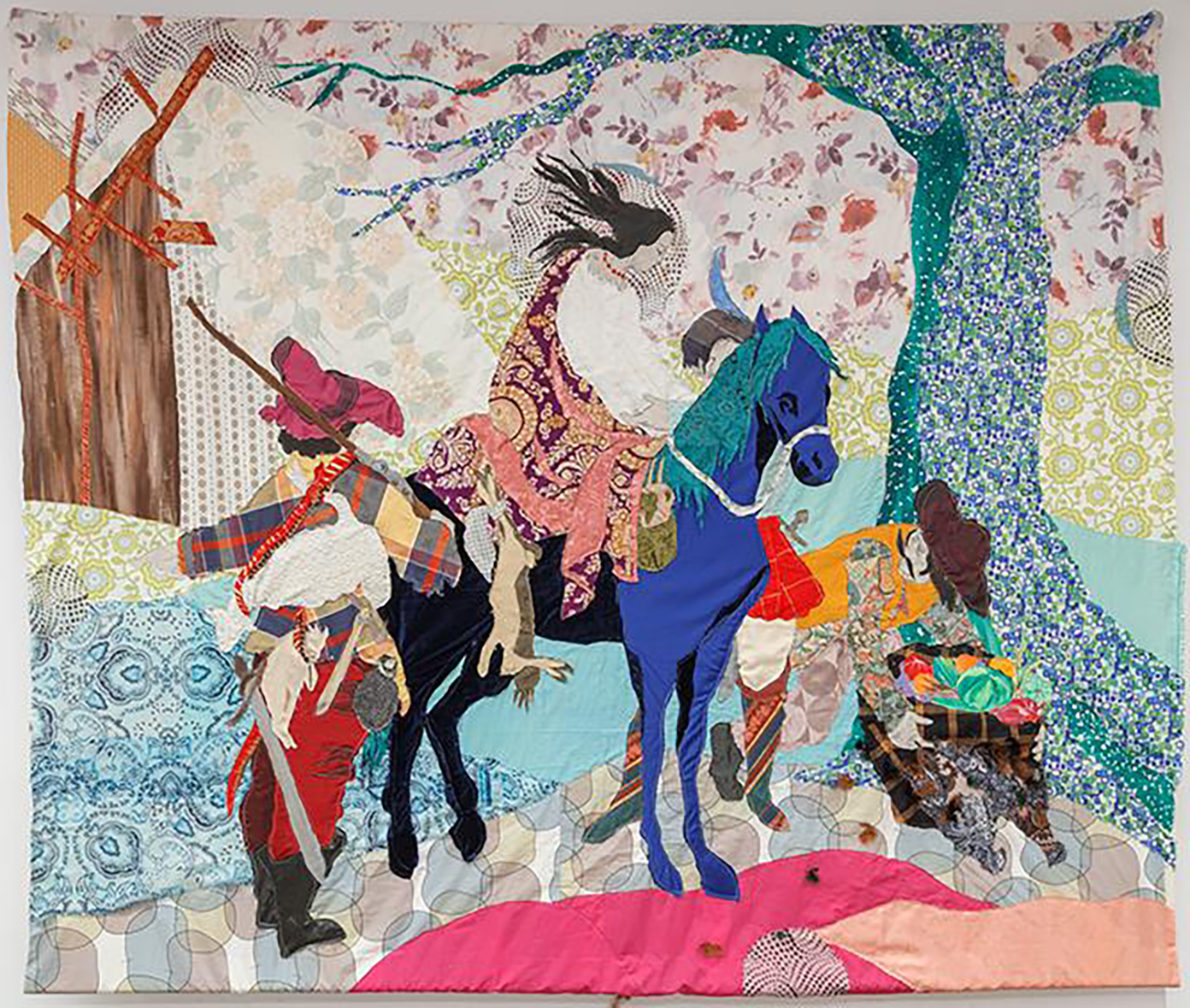

You’ve heard the story before. The poet Orpheus, celebrated for the enchanting quality of his voice, is grieving the sudden death of his young wife Eurydice. In his despair he resolves to harrow the Underworld, where he so impresses the god Hades with his singing that he is permitted to retrieve the shade of his bride and return with her, newly embodied, into the light—on one condition: that he not look back at Eurydice until they have attained the realm of the living. All is proceeding according to plan, and the pair have nearly made it to the world above, when Orpheus, overcome by the suspicion that he has been swindled, turns to assure himself that his silent wife is still following him—only to see her flee away, this time forever, back into the shadows. Małgorzata Mirga-Tas. Out of Egypt. 2021

Małgorzata Mirga-Tas. Out of Egypt. 2021 Death was already about me. I’d recently written two death songs. Not mournful, but peaceful and welcoming. No reason. They just seeped out of me. Then came the Covid infection. It must’ve found me in upstate New York while vacationing with friends.

Death was already about me. I’d recently written two death songs. Not mournful, but peaceful and welcoming. No reason. They just seeped out of me. Then came the Covid infection. It must’ve found me in upstate New York while vacationing with friends.

Gérard Roland came to Berkeley only around the turn of this century. He grew up in Belgium, was a radical student, and after the student movements of Europe subsided, he supported himself for a time by operating trams in the city. When he was wooing his girlfriend (later wife), Heddy, she used to get a free ride in his trams. (A few years back when I visited them one summer in their villa in the Italian countryside near Lucca, Heddy told me in jest that those days she was content with a free tram ride, but now she needed a house in Tuscany to be placated). Gérard is also a good cook.

Gérard Roland came to Berkeley only around the turn of this century. He grew up in Belgium, was a radical student, and after the student movements of Europe subsided, he supported himself for a time by operating trams in the city. When he was wooing his girlfriend (later wife), Heddy, she used to get a free ride in his trams. (A few years back when I visited them one summer in their villa in the Italian countryside near Lucca, Heddy told me in jest that those days she was content with a free tram ride, but now she needed a house in Tuscany to be placated). Gérard is also a good cook.

Every hour of every day I hear the pulsating rush of le Periph and I am reminded that Paris is dead. My dorm is at the very bottom of Paris such that if the city were a ball I’d be the spot that hits the ground. I sit in my windowsill. I watch cars drive on the highway in an unending flow, like blood in veins, fish in streams, but they’re all metal idols of life. Life does not go this fast. Life stops to take a rest.

Every hour of every day I hear the pulsating rush of le Periph and I am reminded that Paris is dead. My dorm is at the very bottom of Paris such that if the city were a ball I’d be the spot that hits the ground. I sit in my windowsill. I watch cars drive on the highway in an unending flow, like blood in veins, fish in streams, but they’re all metal idols of life. Life does not go this fast. Life stops to take a rest. Sughra Raza. Color Burst, Costa Rica 2003.

Sughra Raza. Color Burst, Costa Rica 2003. For many of the ancient philosophers that we still read today, philosophy was not only an intellectual pursuit but a way of life, a rigorous pursuit of wisdom that can guide us through the difficult decisions and battle for self-control that characterize a human life. That view of philosophy as a practical guide faded throughout much of modern history as the idea of a “way of life” was deemed a matter of personal preference and philosophical ethics became a study of how we justify right action. But with the recognition that philosophy might speak to broader concerns than those that get a hearing in academia, this idea of philosophy as a way of life

For many of the ancient philosophers that we still read today, philosophy was not only an intellectual pursuit but a way of life, a rigorous pursuit of wisdom that can guide us through the difficult decisions and battle for self-control that characterize a human life. That view of philosophy as a practical guide faded throughout much of modern history as the idea of a “way of life” was deemed a matter of personal preference and philosophical ethics became a study of how we justify right action. But with the recognition that philosophy might speak to broader concerns than those that get a hearing in academia, this idea of philosophy as a way of life