by Claire Chambers

Language has an important role to play in national identity. One only has to think about the Shaheed Minar in Dhaka. As its name suggests, this monument commemorates what many Bangladeshis view as the shaheeds or martyrs of the Bengali language movement who were killed in Bengal in 1952. The history of West Pakistan’s linguistic imperialism contributed significantly to the 1971 War and the creation of Bangladesh out of Pakistan’s former East Wing.

Language has an important role to play in national identity. One only has to think about the Shaheed Minar in Dhaka. As its name suggests, this monument commemorates what many Bangladeshis view as the shaheeds or martyrs of the Bengali language movement who were killed in Bengal in 1952. The history of West Pakistan’s linguistic imperialism contributed significantly to the 1971 War and the creation of Bangladesh out of Pakistan’s former East Wing.

However, in the context of present-day Pakistan and the Indian subcontinent more broadly, the relationship between language and nation is a complex and contested question. The English language continues to exert a tenacious hold over the subcontinent. In the decades immediately before and after Partition, the majority of South Asians, especially leftists, rejected the use of English for creative purposes, positioning it as an elitist, colonial tongue. For instance, article 4 of the Manifesto of the Progressive Writers Association (1936), sets out the radical authors’ goal ‘to strive for the acceptance of a common language (Hindustani) and a common script (Indo-Roman) for India’. Tellingly, though, this manifesto was drafted in the Nanking Restaurant off Charing Cross Road in London, signalling the inescapable hold of the English language despite the group’s grassroots aims.

Far from making a political choice to write in English, many writers who were educated in the ‘English-medium’ system in Pakistan or Anglo-American countries up to the present have English as their strongest language. As a character in Aamer Hussein’s Another Gulmohar Tree remarks, ‘You don’t choose the language you write in, it chooses you’. The continuing power of English also arises because in the subcontinent there is no single language that has universal support. I do not forget the possible exception of Bangladesh already discussed, but even in that Bengali-dominant country, Urdu speakers are a beleaguered minority upsetting the linguistic equilibrium. Read more »

I’m not sure anyone has ever figured out how to write about music. This is a dangerous statement to make, and I’m sure readers will be quick to point out writers who have been able to capture something as intangible as sound via the written word. This would be a happy result of this article, and I welcome any and all suggestions. I should also say that I don’t mean there are no good music writers; there are, and I have certain writers I follow and read. But the question of how to write about music remains a tricky one.

I’m not sure anyone has ever figured out how to write about music. This is a dangerous statement to make, and I’m sure readers will be quick to point out writers who have been able to capture something as intangible as sound via the written word. This would be a happy result of this article, and I welcome any and all suggestions. I should also say that I don’t mean there are no good music writers; there are, and I have certain writers I follow and read. But the question of how to write about music remains a tricky one.

I got an incredible break when I was thirteen. We moved to Seattle and I entered public school in the sixth grade, after five years of Catholic education. The impact of the change in fortune was all the greater since I had no particular expectations, a good example of the principle that you can never know when things are about to change for the better. It was not just that my least favorite subject, religion, was no longer on the curriculum–that was the least of it. My new school exuded a different mood, much more open, so different to the reform school atmosphere I had become accustomed to. My life began to feel truly blessed.

I got an incredible break when I was thirteen. We moved to Seattle and I entered public school in the sixth grade, after five years of Catholic education. The impact of the change in fortune was all the greater since I had no particular expectations, a good example of the principle that you can never know when things are about to change for the better. It was not just that my least favorite subject, religion, was no longer on the curriculum–that was the least of it. My new school exuded a different mood, much more open, so different to the reform school atmosphere I had become accustomed to. My life began to feel truly blessed. The interest of both Masahiko Aoki and Gérard Roland in institutional economics easily shaded into comparative analysis of economic systems, including different varieties of capitalism and socialism. Since my student days I have been acutely interested in comparative systems and their political economy. In this context like Aoki and Roland I have closely followed developments in China. When I was growing up in Kolkata the leftists around me used to say that the Chinese were better socialists than us, now in the last three decades I have heard in all quarters that the Chinese are better capitalists than us. To reconcile the two I sometimes tell people that if the Chinese are better capitalists now this is partly because they were better socialists then. This is not an entirely flippant comment. By the end of the Mao regime in middle 1970’s, before Deng Xiaoping’s economic reforms started, Chinese performance indicators in basic health, education and rural electrification showed levels unattained by India even by two decades later. This gave China a head start in providing the basis of capitalist industrialization.

The interest of both Masahiko Aoki and Gérard Roland in institutional economics easily shaded into comparative analysis of economic systems, including different varieties of capitalism and socialism. Since my student days I have been acutely interested in comparative systems and their political economy. In this context like Aoki and Roland I have closely followed developments in China. When I was growing up in Kolkata the leftists around me used to say that the Chinese were better socialists than us, now in the last three decades I have heard in all quarters that the Chinese are better capitalists than us. To reconcile the two I sometimes tell people that if the Chinese are better capitalists now this is partly because they were better socialists then. This is not an entirely flippant comment. By the end of the Mao regime in middle 1970’s, before Deng Xiaoping’s economic reforms started, Chinese performance indicators in basic health, education and rural electrification showed levels unattained by India even by two decades later. This gave China a head start in providing the basis of capitalist industrialization.

Early in the story of

Early in the story of

You’ve heard the story before. The poet Orpheus, celebrated for the enchanting quality of his voice, is grieving the sudden death of his young wife Eurydice. In his despair he resolves to harrow the Underworld, where he so impresses the god Hades with his singing that he is permitted to retrieve the shade of his bride and return with her, newly embodied, into the light—on one condition: that he not look back at Eurydice until they have attained the realm of the living. All is proceeding according to plan, and the pair have nearly made it to the world above, when Orpheus, overcome by the suspicion that he has been swindled, turns to assure himself that his silent wife is still following him—only to see her flee away, this time forever, back into the shadows.

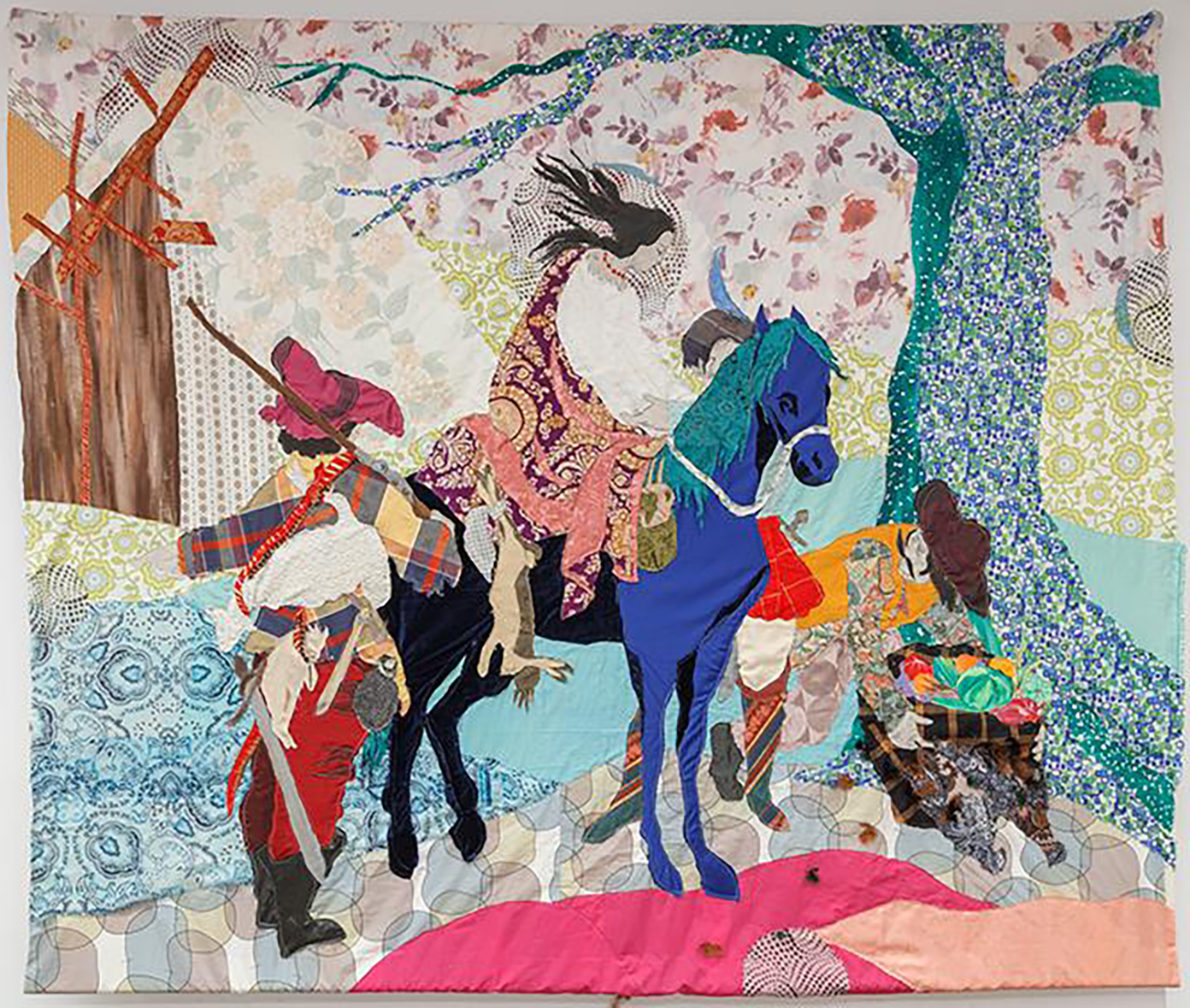

You’ve heard the story before. The poet Orpheus, celebrated for the enchanting quality of his voice, is grieving the sudden death of his young wife Eurydice. In his despair he resolves to harrow the Underworld, where he so impresses the god Hades with his singing that he is permitted to retrieve the shade of his bride and return with her, newly embodied, into the light—on one condition: that he not look back at Eurydice until they have attained the realm of the living. All is proceeding according to plan, and the pair have nearly made it to the world above, when Orpheus, overcome by the suspicion that he has been swindled, turns to assure himself that his silent wife is still following him—only to see her flee away, this time forever, back into the shadows. Małgorzata Mirga-Tas. Out of Egypt. 2021

Małgorzata Mirga-Tas. Out of Egypt. 2021 Death was already about me. I’d recently written two death songs. Not mournful, but peaceful and welcoming. No reason. They just seeped out of me. Then came the Covid infection. It must’ve found me in upstate New York while vacationing with friends.

Death was already about me. I’d recently written two death songs. Not mournful, but peaceful and welcoming. No reason. They just seeped out of me. Then came the Covid infection. It must’ve found me in upstate New York while vacationing with friends.