by David Kordahl

Thomas Kuhn’s epiphany

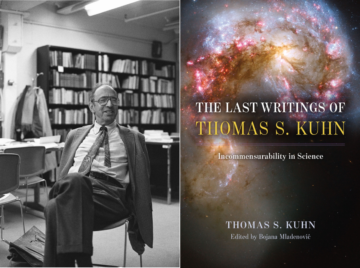

In the years after The Structure of Scientific Revolutions became a bestseller, the philosopher Thomas S. Kuhn (1922-1996) was often asked how he had arrived at his views. After all, his book’s model of science had become influential enough to spawn persistent memes. With over a million copies of Structure eventually in print, marketers and business persons could talk about “paradigm shifts” without any trace of irony. And given the contradictory descriptions that attached to Kuhn—was he a scientific philosopher? a postmodern relativist? another secret third thing?—the question of how he had come to his views was a matter of public interest.

Kuhn told the story of his epiphany many times, but the most recent version in print is collected in The Last Writings of Thomas S. Kuhn: Incommensurability in Science, which was released in November 2022 by the University of Chicago Press. The book gathers an uncollected essay, a lecture series from the 1980s, and the existing text of his long awaited but never completed followup to Structure, all presented with a scholarly introduction by Bojana Mladenović.

But back to that epiphany. As Kuhn was finishing up his Ph.D. in physics at Harvard in the late 1940s, he worked with James Conant, then the president of Harvard, on a general education course that taught science to undergraduates via case histories, a course that examined episodes that had altered the course of science. While preparing a case study on mechanics, Kuhn read Aristotle’s writing on physical science for the first time. Read more »

Ada Beams. Landscape Somewhere in France, 2022.

Ada Beams. Landscape Somewhere in France, 2022.

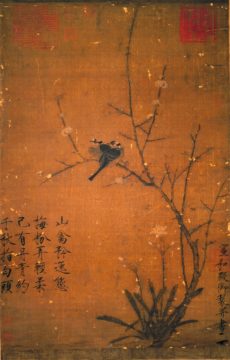

I’m scared of birds. They’re dinosaurs, you know. They descend from the Jurassic when, just like in Jesus Loves Me, ‘they were big and we were small.’ Did you see those huge

I’m scared of birds. They’re dinosaurs, you know. They descend from the Jurassic when, just like in Jesus Loves Me, ‘they were big and we were small.’ Did you see those huge  Lots of people discredit the Myers-Briggs as just a horoscope, but it’s

Lots of people discredit the Myers-Briggs as just a horoscope, but it’s

Sughra Raza. Early Winter Shapes, January 2022.

Sughra Raza. Early Winter Shapes, January 2022. If we are to believe the most prominent of the writers we now lump under the category of “existentialism,” human suffering in the modern world is rooted in nihilism. But I wonder whether this is the best lens through which to view human suffering.

If we are to believe the most prominent of the writers we now lump under the category of “existentialism,” human suffering in the modern world is rooted in nihilism. But I wonder whether this is the best lens through which to view human suffering.

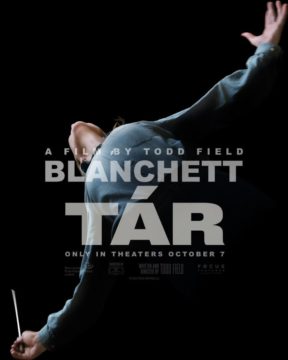

Blanchett’s performance has been much praised, and it is indeed a tremendous thing: she must be near the head of the queue for an Oscar this year. It’s a great performance in a genuinely worthwhile and absorbing film. I don’t think it really expands our understanding of the themes it features: power and the exploitation young hopefuls by the (seemingly) all powerful star, the question of great art and flawed artists and so on, but it’s possible to come out of the movie thinking that it has. Blanchett’s performance has a lot to do with that. So a great performance in a very good rather than great film (assuming such categories can really be employed so neatly).

Blanchett’s performance has been much praised, and it is indeed a tremendous thing: she must be near the head of the queue for an Oscar this year. It’s a great performance in a genuinely worthwhile and absorbing film. I don’t think it really expands our understanding of the themes it features: power and the exploitation young hopefuls by the (seemingly) all powerful star, the question of great art and flawed artists and so on, but it’s possible to come out of the movie thinking that it has. Blanchett’s performance has a lot to do with that. So a great performance in a very good rather than great film (assuming such categories can really be employed so neatly).