by Jonathan Kujawa

In the movies the mathematician is always a lone genius, possibly mad, and uninterested in socializing with other people. Or they are Jeff Goldblum — a category of its own. While it is true that doing mathematics involves a certain amount of thinking alone, I’ve frequently argued here at 3QD that math is a fundamentally social endeavor.

In the movies the mathematician is always a lone genius, possibly mad, and uninterested in socializing with other people. Or they are Jeff Goldblum — a category of its own. While it is true that doing mathematics involves a certain amount of thinking alone, I’ve frequently argued here at 3QD that math is a fundamentally social endeavor.

This weekend I was reminded again of this fundamental fact. Now that we are emerging from covid, in-person math conferences have returned in abundance. I am currently in Cincinnati attending one of the American Mathematical Society’s regional math conferences. It has been wonderful to hear many great talks about cutting edge research. The real treat, though, is the chance to see old friends and meet new people, especially the grad students and young researchers who’ve come into the field in the last few years.

In chats between talks, you learn about the problems people are pondering; their private shortcuts to how to think about certain topics; how their universities handle teaching, budgets, and post-covid life; and, of course, the latest professional gossip. It is nice to be reminded that you are part of a community of like-minded folks.

One of the tentpole events of the conference was the Einstein Public Lecture. They are held annually at one of the AMS meetings and were started to celebrate the one-hundredth anniversary of Albert Einstein’s annus mirabilis. In this case, the speaker was Nathaniel Whitaker, a University of Massachusetts, Amherst, professor. While the mathematical topic of his presentation was his work on finding approximate solutions and numerical estimates to the sorts of partial differential equations which arise in the study of fluid flows, the real story he wanted to tell was his journey from the segregated schools of 1950s Virginia to his role in the 2020s as a leader of a large research university [1]. Read more »

Zaneb Beams. Untitled, 2022.

Zaneb Beams. Untitled, 2022.

‘Wenn möglich, bitte wenden.’

‘Wenn möglich, bitte wenden.’

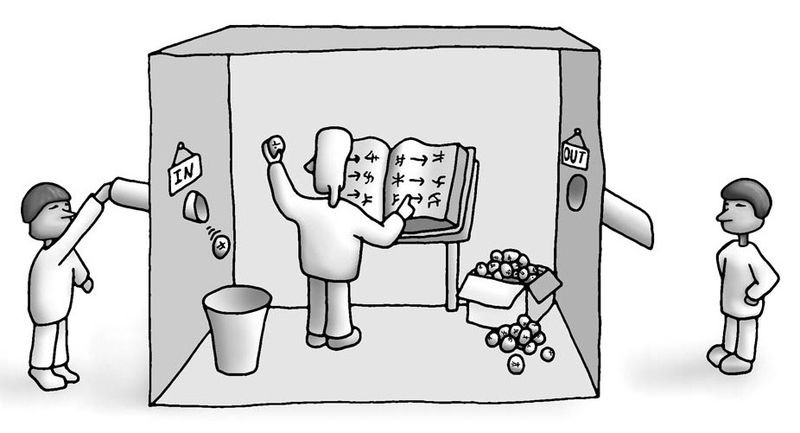

Everyone is talking about artificial intelligence. This is understandable: AI in its current capacity, which we so little understand ourselves, alternately threatens dystopia and promises utopia. We are mostly asking questions. Crucially, we are not asking so much whether the risks outweigh the rewards. That is because the relationship between the first potential and the second is laughably skewed. Most of us are already striving to thrive; whether increasingly superintelligent AI can help us do that is questionable. Whether AI can kill all humans is not.

Everyone is talking about artificial intelligence. This is understandable: AI in its current capacity, which we so little understand ourselves, alternately threatens dystopia and promises utopia. We are mostly asking questions. Crucially, we are not asking so much whether the risks outweigh the rewards. That is because the relationship between the first potential and the second is laughably skewed. Most of us are already striving to thrive; whether increasingly superintelligent AI can help us do that is questionable. Whether AI can kill all humans is not.

Sughra Raza. NYC, April 2023.

Sughra Raza. NYC, April 2023.

Despite many people’s apocalyptic response to ChatGPT, a great deal of caution and skepticism is in order. Some of it is philosophical, some of it practical and social. Let me begin with the former.

Despite many people’s apocalyptic response to ChatGPT, a great deal of caution and skepticism is in order. Some of it is philosophical, some of it practical and social. Let me begin with the former.