by Ethan Seavey

In the growing sector of the contemporary art world which focuses on environmental issues, participants in the art (artists, critics, and the general audience) disagree on the intention of each work of art: does it merit only aesthetic praise, or is it a successful work of climate activism? In my brief internship at Art of Change 21, a French nonprofit association at the intersection of contemporary art and the environment, I frequently encountered this dichotomy. At Art Paris 2022, the association hosted an exhibition centered around artists who deal with environmental themes. My goal is to contextualize some of the artworks present at this exhibition, based on critical theory as well as my own experiences.

When an artist depicts an environmental issue, they want to bring attention to it, and for many in the art world, this attention is enough to be considered powerful activism. In a study for the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Laura Kim Sommer and Christian Andreas Klöckner collected qualitative date based on surveys and cognitive recognition information and determined that art engaging with environmental issues had strong emotional effects upon its audience. This study was conducted at the 2015 UN Climate Conference, for an exhibition of art pertaining to climate issues. (Art of Change 21 was born at this Climate Conference, and had no role in the display of these artworks; the association was present elsewhere in the conference, though, with similar projects.)

What Sommer and Klöckner discovered was that these strong emotional results could be categorized by the artist’s approach to these issues. For example, an artist may approach an issue negatively, displaying pressing problems or a bleak future, or they may approach positively, displaying solutions for problems and a brighter future. After the survey, it was clear that the negative art created strong emotional reactions, of shock, surprise, fear, and anxiety. However, this strong initial emotional response was inversely related to a feeling of a call to action. These pieces presented problems with no solutions, which seem to overwhelm or depress the audience, or at least to create a distance between the audience and the art due to its terrifying content. On the other hand, while positively framed artworks aroused slightly duller initial emotions, in the end the audience left feeling more empowered when presented with pieces which depict solutions to problems, as well as a world that is “interconnected” and “beautiful.” Overall, this study concluded that art can be an effective form of activism, especially when it is created with an optimistic angle towards environmental issues.

While Sommer and Klöckner are satisfied with the idea that an emotional response to art translates into a work of activism, there is some debate on this idea. In her piece “Visual climate change art 2005–2015,” Joanna Nurmus writes, “while [artworks engaging with the climate] gain critical praise, there appears to be a discrepancy between the urgency that artists and curators wish to convey and the contemplative, cathartic effect that these art works produce.” The issue Nurmus finds with comparing art focused on the environment to climate activism is that there is a large gap between the immediate, urgent calls of the artist and the deliberate, long contemplation by the audience. This tension is a frustrating loss of activist potential. Moreover, there is no guarantee that these emotional responses will translate into action by audience. So, Nurmus presents the notion that this branch of contemporary art should rather be contextualized as an aesthetic approach to the problems of the contemporary world. Nurmus’ essay begins with a quote by Walter Benajmin that summarizes this notion: “Mankind[’s] … self alienation has reached such a degree that it can experience its own destruction as an aesthetic pleasure of the first order” (Walter Benjamin, The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, 1936). This quote appears to present a cynical critique of environmentalist art, wherein artists derive a sort of sadistic aesthetic by drawing on the problems we create instead of creating the solutions.

While Nurmus presents an interesting perspective, it seems to ignore the side of environmental art which provides solutions, the exact group that Sommer and Klöckner find the most effective as a means of activism. Both sides seem to discourage pessimistic climate change art, as it only points out problems and warns the audience of a reckoning for the actions of humanity.

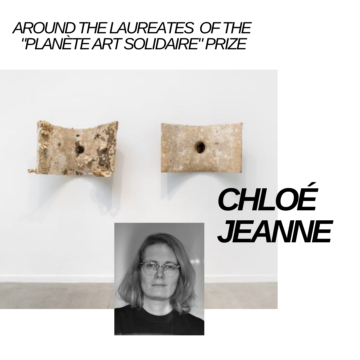

In my own experiences at one of the largest art fairs in Paris, Art Paris 2022, at the Exhibition Around the Laureates of the Planète Art Solidaire Prize, I encountered these different forms of activism. I found most of the pieces at the exhibition to be quite optimistic. Two artists in particular, Côme di Meglio and Chloé Jeanne, chose to represent the positive connection between humanity and nature—coincidentally, through the medium of fungus. Di Meglio created MycoTemple, 2022 a dome created by the roots of the mycelium. The sculpture “awakens our fundamental essential relationship with the living world,” according to di Meglio.

Chloé Jeanne’s Capsules Olfactives, 2021 was made of two mycelium and burlap sculptures, which allow “the development of the mycelium […], thus becoming the link between all the elements that make up the work.” These two artists would fall into the optimistic category, and could potentially leave the audience feeling motivated about their relationship to nature.

Chloé Jeanne’s Capsules Olfactives, 2021 was made of two mycelium and burlap sculptures, which allow “the development of the mycelium […], thus becoming the link between all the elements that make up the work.” These two artists would fall into the optimistic category, and could potentially leave the audience feeling motivated about their relationship to nature.

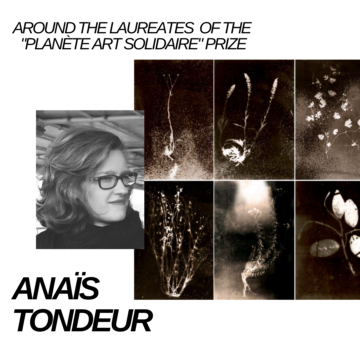

However, not all artists chose the same route. Anaïs Tondeur’s Tchernobyl Herbarium, 2022 is a collection of rayograms, taken by directly imprinting plants born in the irradiated soils of Chernobyl onto photosensitive plates. I worked directly with Tondeur, in the careful installation and dismantling of her art work, and though her attitude was very positive and kind, her artwork is a grim reminder of the terrible effects mankind has had on the Earth. Decades after the catastrophe at Chernobyl, its effects linger in the flora of the site. It leave the impression that humans have wronged the Earth irreversibly, a darker message than the rest of the artworks at the exhibition.

However, not all artists chose the same route. Anaïs Tondeur’s Tchernobyl Herbarium, 2022 is a collection of rayograms, taken by directly imprinting plants born in the irradiated soils of Chernobyl onto photosensitive plates. I worked directly with Tondeur, in the careful installation and dismantling of her art work, and though her attitude was very positive and kind, her artwork is a grim reminder of the terrible effects mankind has had on the Earth. Decades after the catastrophe at Chernobyl, its effects linger in the flora of the site. It leave the impression that humans have wronged the Earth irreversibly, a darker message than the rest of the artworks at the exhibition.

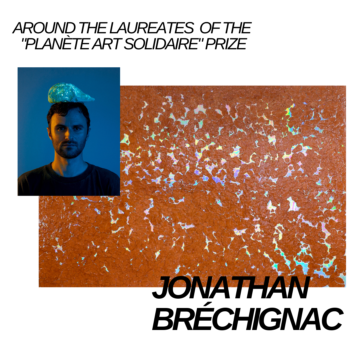

One more artist, Jonathan Bréchignac, created an art work which seemed to fit in the gray area in this spectrum of black and white. His artwork, PRIMAL_LUTUM_SYNTHETICA_012022, 2022 is a stunning piece to approach. It is a massive tableau with a base of a reflective, iridescent film which is covered partially by bright orange clay. The piece is said to “create a ‘poisonous beauty’ that reveals our origins and questions the idea of ‘progress’ and its consequences on the environment. The healing dimension of clay transcends this duality and appeases the future.” Now, personal bias alert: I loved working with Jon. He was a genuinely kind man (which can be hard to find in Paris). He helped the association in our assembling and dismantling of the entire exhibit. At the art fair he became the guy I could ask any question, and I became the person who could hold the other corner of the painting he was carrying. And, on top of all that, he was absolutely brilliant; he produced my favorite piece in the exhibition, and the one with the most complex approach. His piece does not deny the positive or the negative, instead weaving them together for an honest depiction of the world. As an artist, he does not deny labels like “activist” and “environmentalist,” unlike some of the artists represented at the exhibition.

One more artist, Jonathan Bréchignac, created an art work which seemed to fit in the gray area in this spectrum of black and white. His artwork, PRIMAL_LUTUM_SYNTHETICA_012022, 2022 is a stunning piece to approach. It is a massive tableau with a base of a reflective, iridescent film which is covered partially by bright orange clay. The piece is said to “create a ‘poisonous beauty’ that reveals our origins and questions the idea of ‘progress’ and its consequences on the environment. The healing dimension of clay transcends this duality and appeases the future.” Now, personal bias alert: I loved working with Jon. He was a genuinely kind man (which can be hard to find in Paris). He helped the association in our assembling and dismantling of the entire exhibit. At the art fair he became the guy I could ask any question, and I became the person who could hold the other corner of the painting he was carrying. And, on top of all that, he was absolutely brilliant; he produced my favorite piece in the exhibition, and the one with the most complex approach. His piece does not deny the positive or the negative, instead weaving them together for an honest depiction of the world. As an artist, he does not deny labels like “activist” and “environmentalist,” unlike some of the artists represented at the exhibition.

If an art work has a depiction of environmental issues, is it necessarily a work of activism? Well, maybe not necessarily—but I think it would be difficult to argue the reverse, because artists create something to draw attention to it. The nonprofit Art of Change 21 would frequently deal with these issues of syntax. The intersection of contemporary art and environmental issues is a very new development, and the proper terms aren’t clearly distinguished. Are artists like Bréchignac artists engaged in environmental issues, or activists using art as their medium? Probably the answer is somewhere in the middle.

Regardless, Art of Change 21 would not exist if it did not believe that these artists could change the world, and I am left in agreement with them. Sometimes, it was hard for me to see the bigger picture. Working with the association, I would wonder if supporting art speaking about the environment was enough to change anything. In fact, I was hung up on the idea that art is detrimental to the environment, and of course it is, somewhat depending on the artist. Artists like Di Meglio and Jeanne created art from growing fungus and recycled burlap, but those like Bréchignac and Tondeur use synthetic materials, in effect further harming the world they’re trying to save. The cynical side of me sees this paradox and wants to condemn these artists further by agreeing with Nurmus, in thinking that aesthetic is the intent and that an emotional response is not enough for real social change.

However, I changed my mind because of the founding president of Art of Change 21, who would frequently remind me of a universal truth: it’s the artists who pave the path first, “et les autres qui suivent.” I realized that the benefits of this environmental art was the social change which will follow it. These emotional responses can seem fleeting, but an artwork doesn’t always cause immediate action. Instead, sometimes it lingers, creating gradual positive change. Of course, Sommer and Klöckner found that optimistic pieces are more effective in this regard, but I found myself contemplating Bréchignac’s work the most, a piece which lingered in the gray area. I am left with the conclusion that a successful work of artistic activism is the creation of a piece which engages with environmental issues and which leaves you thinking about it as you walk away from it.

Sources:

Sommer, Laura Kim and Klöckner, Christian Andreas, “Does Activist Art Have the

Capacity to Raise Awareness in Audiences?— A Study on Climate Change Art at

the ArtCOP21 Event in Paris.”Norwegian University of Science and Technology,

2019.

https://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2Faca0000247

Nurmus, Joanna. “Visual climate change art 2005–2015: discourse and practice.”

WIREs Clim Change 2016, 7:501–516. doi: 10.1002/wcc.400,