by Mike Bendzela

[This will be a two-part essay.]

Ischemia

When the burly, bearded young man climbs into the bed with my husband, I scooch up in my plastic chair to get a better view. On a computer screen nearby, I swear I am seeing, in grainy black-and-white, a deep-sea creature, pulsing. There is a rhythmic barking sound, like an angry dog in the distance. With lights dimmed and curtains drawn in this mere alcove of a room, the effect is most unsettling. That barking sea creature would be Don’s cardiac muscle.

It is shocking to see him out of his work boots, dungarees, suspenders, and black vest, wearing instead a wraparound kitchen curtain for a garment. He remains logy and quiet while the young man holds a transducer against his chest and sounds the depths of his old heart, inspecting valves, ventricles, and vessels for signs of blood clots. This echocardiogram is part of the protocol, even though they are pretty sure the stroke has been caused by atherosclerosis in a cerebral artery.

The irony of someone like Don being held in such a room, amidst all this high-tech equipment, is staggering. He is a traditional cabinetmaker by trade and an enthusiast of 19th century technologies, especially plumbing systems and mechanical farm equipment. He embarked on a career as an Industrial Arts teacher in Maine in the 1970s but abandoned that gig during his student teaching days when he decided it was “mostly babysitting, not teaching.” The final break came when he discovered that one of his students could not even write his own name, and his superiors just said, “Move him along.”

In the dim quiet, while the technician probes Don’s chest, I mull over the conversation we just had with two male physicians. They had come into the room and introduced themselves as neurologists—Doctors Frick & Frack, for all I remember.

“You’re not a very well-controlled diabetic,” Dr. Frick had said.

Don just stared at him, blankly.

“They took away his hearing aids,” I said.

Dr. Frick spoke up. “Your A1c is 9.5. You need to see an endocrinologist!”

Dr. Frack threw in, “Type 1 diabetics have an 80% greater risk of stroke!”

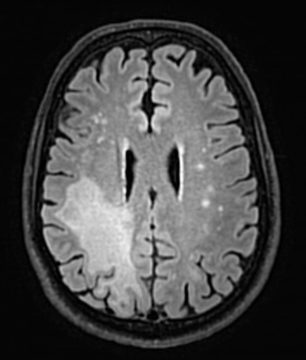

The neurologists brought up on a computer screen a picture that looked like a photographic negative of a walnut: Don’s brain, done up in bleak colors of the night sky. The men pointed out two pinpoints of light on the CT scan, one in the left rear quadrant, the other on the left side.

“So that’s the ischemia,” I said.

Dr. Frick raised his eyebrows and said, “Yes.” I actually knew one of his words.

I regarded the two little points of light and felt a little hopeful. “It looks like it could have been worse.”

“It’s bad enough,” said Dr. Frack. He aimed his pen at the screen and drew circles in the air. “This is the left posterior cerebral artery. It’s the one that’s blocked. You can see how it’s a darker shade than the rest of these. See how bright and clear these other vessels are?”

The burly guy rolls out of Don’s bed.

The echocardiogram now complete, Don gets wheeled upstairs for yet another snapshot of his brain, this time a longer, more involved exposure—an MRI. It is a picture we will not see until after he is released from the hospital.

Hemianopsia

On Don’s last day at the hospital in Portland, after he has been moved to recovery, he says, matter-of-factly, “You just fell out of my right field of vision.” I am standing next to his bed, trying to ignore the noisy TV his roommate is not even watching.

I recall the stroke exam from my EMT training, even though I have not run calls in a couple of years. “Grip my fingers and squeeze,” I say. I believe I feel weakness in his right hand.

I pick up the call button and press it to summon help. The wait is intolerable, so I press the button again.

Eventually, someone from the staff puts her head in the door. “What’s up?”

“I think he’s having another stroke.”

“OK. I’ll get someone.” And she leaves us there.

Eventually, a doctor comes in to put Don through the paces of a neurological exam. She has him sit up on the edge of the bed. I can tell he is weary of it.

“Lift your arms . . . smile . . . bend your knees . . . look over here . . . now look over there. . . .” She stands back. “I don’t see any deficits right now.”

“I swear I felt weakness on his right side,” I tell her.

“Oh, I believe you.”

Don tells her he cannot see anything on the right.

“I’ll let the neurologist know.”

And then she leaves, like nothing has happened.

We wait. Don lies there. We call it “rotting.”

“I’d rather be in the attic insulating around the chimney,” he says.

And that awful television: It barks TRUMP! TRUMP! over the inert body of Don’s roommate. Don has asked him to shut the damned thing off, but the guy just uses the remote to reduce the sound a little then rolls over in bed.

When I complain, a nurse encourages us to take a stroll down the hall.

I help Don shuffle out into the sun-lit hallway in his kitchen curtain. We walk toward a restful little nook, with some chairs for reading, paintings on the walls. He stands transfixed by one painting; it is large, perhaps two by three feet; a classic, romanticized New England village; white clapboard church by a bay, boats scattered on the water, farms and fields nearby; blue sky, greenery, cows.

“That’s weird,” Don says.

The perspective has that stacked look of quaint, Primitivist art; the background stands right on top of the foreground. Boats seem to float in the sky near the clapboard church.

“What’s weird?”

“I can only see from here—” He holds his right hand flat up in front of his nose and sweeps it to the left. “–to here.”

I stare at the New England village scene and try to comprehend. “What about those cows in the field on the right?”

He turns his head, slightly. “If I scan the picture, I can see them, but if I just look straight at it I can’t. It’s so bizarre.”

The uncanniness of the brain injury is making him a little giddy. It is an injury–hemianopsia–from which we both still think he will recover.

Alexia

After Don is moved across town to rehab, I cancel my writing classes at the university so I can witness some of his therapy.

I visit in mid-morning, just before he is due for speech therapy. Don is pissed off because his blood sugars are high; they changed his insulins and dosages in the hospital, and this continues into rehab. He no longer has control of his injections or glucose testing: nurses do. “We don’t like hypoglycemia here,” they tell him.

And the food sucks. “Industrial, prefab everything,” he calls it. He is used to fresh garden vegetables, home-cured pork, hand-churned butter.

The therapist enters, introduces herself to us, then sits in a chair near Don’s bed with her white board, marker, and eraser. She looks like a tidy scholar, short brown hair, glasses. Even though she is called a “speech and language” therapist, she works with Don on visual tasks, identifying shapes, as well as reading and writing.

On her white board she writes a list of words:

SQUARE

CIRCLE

STAR

Holding the board up so Don can see it, she says, “Read these words aloud for me.”

Don holds out his hand. “Can I see that?” He takes the white board from her, sets it on his lap and pores over it. He hands the board back to her. “Is it even English?”

The therapist erases the words and draws a five-pointed star. “What is this?”

“A star.”

“Good.” She erases, draws a circle. “What about this?”

“Circle.”

“Good.”

She draws a square on the board and gives it to Don. “Write down the word for this shape.”

Don sits up in bed with the board in his lap and takes the marker into his left hand. In his tiny, crabbed, carpenter’s hand he prints—neatly—

square

“That’s weird,” I say.

“That’s good,” the therapist says. She takes the board from Don, erases, and prints,

TRUCK

She holds up the board.

Don looks at it and shakes his head. “Looks like Russian to me.”

“What the hell—” I start.

She erases and hands him the board. “Draw a truck.”

Don laughs. “Sure.” He takes up the white board and marker. He sets it in his lap and draws a cute little schematic of a dump truck, fat tires, fenders and all.

“Good! . . . Now underneath, write the word, if you can.”

Slowly, in his crabbed hand . . .

truck

We all sit there, taking this in.

“He can’t read,” I say, “but he can write?”

“The brain is a very mysterious thing,” the therapist says.

“That’s so cool,” I say, and I begin to cry a little.

Why did I say that? Because I have spent a good part of my life reading books about language and the brain, about evolution and how the mind works. The peculiar effects of stroke damage are often cited as evidence for the localized character of brain architecture. Don has apparently lost his reading module, not his writing module, because the stroke in his occipital lobe caused an insult to his vision, not his literacy. He has “alexia without agraphia.” It is terrible, but it could have been much worse. I kick myself for reflexively buying into that bland denial masquerading as optimism.

“Did you hear that?” the therapist says to Don. “He thinks you’re cool.”

Infarct

On a separate floor of the same building as the rehab facility, we sat in a waiting chamber while a nurse took Don’s blood pressure, heart rate and oxygen saturation. A short, thin woman came in and introduced herself. She gripped our hands then performed yet another neurological exam on Don: smile symmetry, limb movements, eye movements, the works. Then the doc sat at a computer and looked over Don’s hospital records.

“Your stroke has evolved.”

“It what?” I asked.

“Evolved,” she articulated, crisply.

We gathered that, downstream from the blocked artery, neurons were still expiring, like little soldiers in mustard gas. This perhaps explained his continued listlessness, his unsteadiness on his feet, his faulty memory. He could not remember names for important things around the house; he kept referring to the porch as the “parlor,” slapping himself on the side of the head and calling himself “gimp.”

The neurologist said the loss of Don’s right visual field was probably permanent, but with continued rehab sessions he might be able to regain part of his reading ability.

I was still thinking about that blockage that had originally brought him here.

“That cerebral artery,” I said to the doc, “I’m afraid it’s going to keep giving off embolisms.”

“You don’t have to worry about that,” she said, offhandedly. “That vessel is gone.”

It was like a trapdoor had suddenly let go beneath our feet and we hung there, in mid-air.

The neurologist had the goods to show us—the most recent MRI scan. She brought up the black-and-white snapshot of Don’s brain, one taken the day after his admittance to the hospital. It looked different: instead of just two bright dots, the left hemisphere looked as if it had been invaded by cobwebs. It was shot through with silvery-white wisps—infarction.

Like Doctors Frick & Frack before, she used her pen to draw our attention to the screen, making repeated circles over the webby area. “This is what I would call patchy damage.”

As she sat in her chair in front of the computer screen, Don and I stood on either side, gawking at the image, trying to fathom what it meant.

The neurologist turned in her chair and touched Don’s sleeve, water welling up in her eyes.

“I’m glad to see you standing here,” she said. “You could be so much worse off.”

**

Part Two of “Could Be Worse” will appear next month.

For my husband Don, who celebrates his 70th year this week–7 years after the stroke–and his 51st year living with Type 1 diabetes.

__________________

Image

“MRI of patient with PML” by National Institutes of Health (NIH) is marked with Public Domain Mark 1.0.