by Jonathan Kujawa

In the movies the mathematician is always a lone genius, possibly mad, and uninterested in socializing with other people. Or they are Jeff Goldblum — a category of its own. While it is true that doing mathematics involves a certain amount of thinking alone, I’ve frequently argued here at 3QD that math is a fundamentally social endeavor.

In the movies the mathematician is always a lone genius, possibly mad, and uninterested in socializing with other people. Or they are Jeff Goldblum — a category of its own. While it is true that doing mathematics involves a certain amount of thinking alone, I’ve frequently argued here at 3QD that math is a fundamentally social endeavor.

This weekend I was reminded again of this fundamental fact. Now that we are emerging from covid, in-person math conferences have returned in abundance. I am currently in Cincinnati attending one of the American Mathematical Society’s regional math conferences. It has been wonderful to hear many great talks about cutting edge research. The real treat, though, is the chance to see old friends and meet new people, especially the grad students and young researchers who’ve come into the field in the last few years.

In chats between talks, you learn about the problems people are pondering; their private shortcuts to how to think about certain topics; how their universities handle teaching, budgets, and post-covid life; and, of course, the latest professional gossip. It is nice to be reminded that you are part of a community of like-minded folks.

One of the tentpole events of the conference was the Einstein Public Lecture. They are held annually at one of the AMS meetings and were started to celebrate the one-hundredth anniversary of Albert Einstein’s annus mirabilis. In this case, the speaker was Nathaniel Whitaker, a University of Massachusetts, Amherst, professor. While the mathematical topic of his presentation was his work on finding approximate solutions and numerical estimates to the sorts of partial differential equations which arise in the study of fluid flows, the real story he wanted to tell was his journey from the segregated schools of 1950s Virginia to his role in the 2020s as a leader of a large research university [1].

Dr. Whitaker grew up in coastal Virginia. He didn’t know it t the time, but it was only a few miles from Fort Monroe — the location where the African slave trade to the US began in 1619. His elementary school was segregated. The lie of “separate but equal” meant that the school was short on equipment, and the books were hand-me-down discards from the white-only schools. The local drive-in movie theater had a fence down the middle to separate the white and Black patrons. Whitaker’s grandparents were sharecroppers, his parents had only an elementary school education, and the opportunities for even someone like Nathanial Whitaker in this time and place were few.

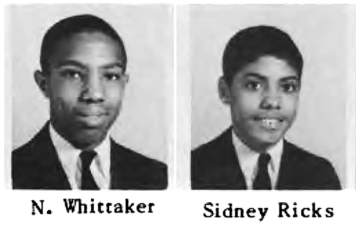

In 1965, under the duress of federal desegregation efforts, Virginia began to allow students to choose to attend any school in their city. Despite his parents’ misgivings, Nathaniel Whitaker and his friend Sidney Ricks decided to attend the local white junior and high schools. As some of the very few students who came over from the Black schools, they felt isolated and unprepared. By supporting each other and through sheer hard work, Whitaker and Ricks were able to take advantage of the opportunities and resources of their new schools.

After earning a degree in economics from Hampton Institute (now Hampton University), a local HBCU, Whitaker spent several years working in industry. Finding the work dull, he eventually took math classes in the evenings and then decided to take a shot at graduate school. The only graduate program which accepted Whitaker with funding support was the University of Cincinnati [2]. After earning his Master’s degree, Whitaker took the advice of a mentor and finished his education at the University of California, Berkley. The Berkeley math department provided more opportunities and was also known at the time for having a cohort of Black graduate students [3].

With the help of his fellow students and several key mentors. Dr. Whitaker completed his degree at UC Berkeley in 1987. His family was able to come to the graduation. Every parent worth the name is proud when their children accomplish something remarkable. But in Dr. Whitaker’s case, he realized his graduation carried extra significance. As he wrote:

As I have grown older, I have come to realize more and more how much my parents had been shackled by racism. There were many esteemed, educated people at the graduation ceremony, but my parents are my heros. For me, receiving my PhD showed them what they could have accomplished without those shackles of Jim Crow holding them down. I stand on their shoulders. People in the community where I grew up did not know what a person with a PhD in mathematics does. — Nathaniel Whitaker

Dr. Whitaker went on to an illustrious career as a professor, department chair, and now dean at the University of Massachusetts. Despite his claims that he’s thinking of retiring, he doesn’t seem to be slowing down. He recently worked with another UMass professor, Annie Raymond, to develop a college course that they teach at the Hampshire County Jail.

Since I’m not bothering to talk about Dr. Whitaker’s actual research into fluid flows, let me instead share a mind-bending and totally undoctored video of laminar flow. It both demonstrates the time-reversible nature of the Stokes differential equation and also seems to violate the second law of thermodynamics:

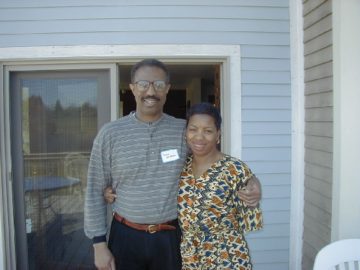

The reoccurring theme in Dr. Whitaker’s presentation was the importance of community. He spoke of how his parents valued education even though or, more likely, because they didn’t have it themselves. Growing up in 1950s Virginia was the source of many challenges but it also meant that Katherine Johnson, Dorothy Vaughan, and several of the other Black women who worked as computers for NASA were his neighbors and family friends. Sidney Ricks prompted Whitaker to make the uncomfortable move to the white school system. It was his professor, Diego Murio, at the University of Cincinnati, who sparked a love of numerical analysis and convinced Whitaker that he ought to go to Berkeley. And there were many friends, colleagues, collaborators, and students along the way that Whitaker called out for their role in his journey [4]. Not least is Dr. Whitaker’s wife of 38 years, Dr. Shirley Jackson Whitaker.

Dr. Whitaker also made a more subtle point. Not only are individuals important, so is the community as a whole. He said that, ironically enough, the confidence he developed in his segregated elementary school helped support him during the isolation and invisibility of being one of the few Black people in his high school. Likewise, he pointed out that an important reason he was able to thrive at Berkeley and UMass was the people around him. People with whom to host potluck dinners, play tennis, and lend a friendly ear.

The hours between the classes, the seminars, and the mentoring sessions can be awfully lonely. Any organization which wants to support its members needs to think about the role of community. It takes both bricks and mortar to build a wall, after all.

[1] While I won’t spend time on it, the mathematics of the talk was also quite interesting. Partial differential equations could not be farther from my own research background. PDEs tend to be quite technical and the talks can be brutal (I’ve endured my share over the years!). In contrast, Dr. Whitaker gave an accessible talk describing how mathematics is used to model and predict how fluids flow when we frack oil reserves; our body pumps blood through small veins; and Jupiter maintains its Great Red Spot.

[2] Which, of course, made their hosting of Dr. Whitaker’s Einstein Lecture especially evocative.

[3] At the time the University of Cinncinati had exactly one Black graduate student (Whitaker). UC Berkeley had a group, and the department was committed to bringing in women and other underrepresented students with each incoming class. Then and now, the median number of Black students in a US math graduate program is zero.

In 2018, the AMS reported 1,960 PhDs were granted in the US. Of those, 27 (1.4%) were to Black mathematicians; 8 (0.4%) were to Native American, Hawaiian, or Pacific Islander mathematicians; and 34 (1.7%) were to Hispanic mathematicians.

[4] In a funny coincidence, one of Dr. Whitaker’s PhD students, Dr. Gregory Herring, is a faculty member down the road from me at Cameron University.