by Jochen Szangolies

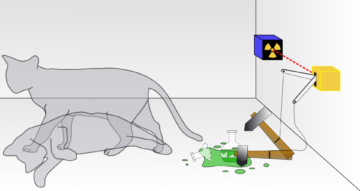

There seems no obvious link between tall war-tales, shared among a circle of German aristocrats in the 1760s, and quantum mechanics. The former would eventually come to form the basis of the exploits of Baron Münchhausen, the partly fictionalized avatar of Hieronymus Karl Friedrich, Freiherr von Münchhausen, famous for his extravagant narratives, while the latter is the familiar, yet vexingly incomprehensible, theory of the ‘microscopic’ realm developed more than 150 years later. Both, however, seem to equally beggar belief: which is stranger—riding a cannonball across a battlefield (and back), or seemingly being in two places at once? Reconnecting a horse bisected by a falling gate, or deciding the fate of a both-dead-and-alive cat by opening a box?

But beyond mere bafflement, the stories of Münchhausen’s exploits have inspired a philosophical conundrum relevant to the question of quantum reality. Perhaps the Lügenbaron’s most famous story, it concerns his getting trapped in the swamp on his horse, a conundrum which is solved by pulling the both of them out by his own plait of hair.

The power of this image was appreciated by Friedrich Nietzsche, who in Beyond Good and Evil likened the concept of ‘free will’ to being a causa sui, “with a courage greater than Munchhausen’s, pulling yourself by the hair from the swamp of nothingness up into existence”. But in its most famous formulation, due to the German philosopher Hans Albert, who died last week at the venerable age of 102, it comes in the form of the Münchhausen-trilemma. Any attempt at finding a final justification, according to Albert, must end in either of the following options:

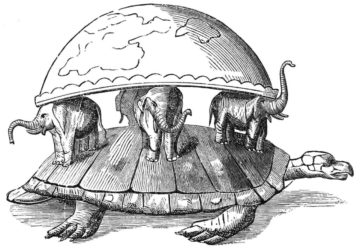

Infinite regress: whatever is supposed to yield this justification must be justified itself (turtles all the way down)

Circularity: the justification of some proposition presumes that very proposition’s truth (the turtle stands on itself)

Dogma: the regress is artificially broken by postulating a ‘buck-stops-here’ justification that is assumed itself unassailable and without need for further explanation (the final turtle is supported by nothing)

Each of the above seems to frustrate any attempt at finding any sort of certain ground to stand on—and, lacking Münchhausen’s ability to drag ourselves out by our own hair, sees us firmly bogged down in the mire of uncertainty. An infinite regress will never reach its conclusion, thus, like a parent frustrated with an endless series of ‘Why?’, we may be tempted to cut it short by an imagined regress-stopper—‘because I/God/the laws of physics say so’, but just because the journey stops, doesn’t mean we’ve arrived at our destination.

What can be done in the face of the trilemma?

Hans Albert himself, and most famously the Austrian-British philosopher Karl Popper, proposed that while we cannot aspire to certainty in our knowledge, we can approach it through the via negativa of fallibilism: holding every belief as provisional up to its eventual defeat, thereby shedding wrong beliefs and building confidence in the surviving ones. The resulting critical rationalism rejects the idea of a certain foundation for our knowledge, and instead proposes that our beliefs are subjected to constant critique—turning the epistemological process inside out, from that of an architect erecting a building on solid ground, to that of a sculptor laying bare the form hidden in the block of marble by chipping away what does not belong.

Applied to the scientific process, this leads to the doctrine of falsificationism: a hypothesis, to be accepted as scientific, must, in principle, allow its being empirically falsified—there must exist an experiment whose outcome suffices to reject it, should it prove unfavorable. This simple picture has attracted sustained criticism almost immediately, from philosophers like Thomas Kuhn, Paul Feyerabend, Imre Lakatos, and others. Nevertheless, it is still influential in the natural sciences.

I won’t enter into this debate, here, other than to note a couple of complicating points concerning the relation between the premises (and promises) of scientific theories and what’s out there, for real. We might want to build confidence in our theories by noting that their success seems to intimate them getting something right about the world. After all, we couldn’t have put a person on the Moon on the basis of a wrong theory!

The problem is, of course, that that’s exactly what we did. The calculations needed to successfully land on the Moon are performed entirely within a Newtonian framework—a framework that contains forces acting instantaneously across arbitrary distances, unlimited speeds, perfectly rigid bodies, infinitely precise quantities, an independent background space and uniform flow of time, none of which exist according to theories in better accord with experimental data. That is, we can mount successful endeavors in the world on the basis of theories which radically mislead us about the world’s constitution.

Against this, one might hold that Newtonian theory approximates its more inclusive successors—quantum mechanics, the special and general theories of relativity—in the relevant regime. But this is not an answer—this is merely a restatement of the mystery: how can one theory ‘approximate’ another, while postulating an entirely different inventory for the world? At the very least, this should undermine our credence in the existence of the entities postulated by our current best theories: if these are accepted only provisionally, pending falsification, whether what’s out there is what they say should be out there seems, at best, dubious.

Moreover, even upon eventually discovering any sort of ‘final’ theory, and even apart from the impossibility of ever fully accepting it as a final theory, we find we’re still just standing on air (or swamp, as the case may be): “What,” as Stephen Hawking memorably asked, “is it that breathes fire into the equations and makes a universe for them to describe?”

Substance And Subject

But what way out could there be? Neither of the trilemma’s options suggests a feasible path; and together, they seem to run the gamut. However, I want to argue that the trilemma only poses itself upon the acceptance of a certain metaphysical picture, which is too often still assumed without question—indeed, without awareness that one is making any assumption that might fail to hold, at all. Like water in David Foster Wallace’s famous commencement speech, we are so well enmeshed within it that it scarcely seems noticeable, at all—there seems no imaginable contrast against which to throw it into relief. Like water needs the possibility of not-water to become an object of inquiry, so does this metaphysical picture need a feasible alternative to enter into our discourse as anything other than an unexamined background.

I’m talking, here, about the metaphysics that conceives of the world as being constituted of objectively existing elements, of substances that literally ‘stand on their own’ (from Latinsubstare, standing beneath, like the final turtle upon which the whole teetering tower is balanced), of independently existing facts, and on the other side of the equation individual subjective loci of experience, of observers investigating this substantial backdrop without influencing it.

In the previous two columns, I have outlined reasons to be skeptical of this metaphysics. The Kochen-Specker theorem, I argued, gives us reason to disbelieve an objective grid of facts that lie passively awaiting their discovery. Then, extending the quantum mechanical description to observers, as in the Frauchiger-Renner argument, provides us with grounds to believe in a picture where there is no grand, overarching single story to be told about the world, but rather, a Rashomon-like tapestry of interwoven narrative threads that can’t be unified under a single framework, but which are all necessary for a complete picture.

There are caveats to both these views, and it is possible to uphold the metaphysical view of an objective world being investigated by independent subjects in spite of them. However, what they do show is the possibility of an alternative; and whereas the case made there is a negative one, here, I want to concentrate on positive reasons for accepting this divergent view.

We begin, first, by noting that there seems to be at least one kind of knowledge that is not afflicted by the Münchhausen-trilemma: knowledge of certain subjective states does not seem to need any further justification. If I have a headache, I don’t need to collect evidence, on the basis of which I then conclude I must be having a headache; it just hurts, and that’s how I know. Heaving a headache and believing that I have a headache seem inseparable: I can’t have a headache and be in denial about it, because if I didn’t feel the pain, I wouldn’t have a headache, and if I feel the pain, I believe I’m in pain.

In my own approach to the philosophy of mind, such states are modeled by propositions such that their truth implies their being known—that is, if p is true of S, then S believes that p is true of S (and since therefore S believes something true, S knows that p). There is no need for further justification, nor do we collapse to circularity.

Relative Reality

This yields a possible stepping stone of certainty on the ‘subjective’ level. However, within a metaphysics separating subjective and objective spheres, we still haven’t won much: while knowledge of our own subjective experiences may rest on solid ground, the same cannot be said about the world outside.

The second step in bringing the subjective and the objective in closer accord is provided by a thought experiment I’ve grown fond of. Imagine, if you will, a world without humans, without any observers, without any conscious entities whatsoever. What did you come up with? Desolate wind-blown landscapes under the light of a harsh sun? Billowing cosmic nebula, dotted by stars? Planets rolling through the void? Or perhaps even a world, lush with life, but without anything of greater cognitive capacity than, say, an amoeba?

Whatever you imagined, however, was wrong: it will always be a world as seen from a certain perspective, as present in some observer’s—your—experience. There is at least one conscious entity in the picture, the one that’s viewing it. The world can’t be thought absent the context of its being experienced—this is water: what we call the ‘world’, and imagine to have an existence in the purely objective sphere, is in fact always mediated through some subjective point of view. It is only through ignoring this intrinsic perspective that we can construct the notion of the objective. The world only appears to us as a perception of the world.

The radical idea, then, is what brings us back to the many-threaded metaphysics previously argued for: that the world, ultimately, is nothing but the collection of perspectives on it; that the objective world has only existence as a sort of limiting case, where we imagine the union of all of the perspectives on it—which is, however, never achieved.

But how does this perspectivalism allow us to attack the foundations on which the Münchhausen-trilemma rests, and find a way to grounded knowledge?

It is here that the considerations from quantum theory again become important. A central quantum phenomenon is that of entanglement. For our purposes, an entangled state is one whose components may not have a definite value for a given quantity, but which nevertheless shows correlation regarding that quantity. In the notation of the previous column, [↑↓,↓↑] denotes a state of two subsystems (e.g. particles, perhaps electrons) such that, if you find ‘↑’ (‘spin up’) upon measuring one, you know that the other must be ‘↓’ (‘spin down’), and vice versa. Yet, neither individual system has a predefined state on its own.

But now put yourself in the shoes of one of the particles: if your spin is up, the other’s spin will be down—and vice versa. Relative to your state, the ‘rest of the world’ will assume a definite state, even if the total state is one of maximal indefiniteness. That is, the world can be decomposed into two perspectives, one which ‘sees’ a spin-down particle, and another which sees a spin-up particle. If we thus take some certain ‘internal’ state as given, we obtain a certain state of the ‘external’ world in response.

This is a sort of relational creation from nothing: we are not proposing a world coming into being in a sudden puff of creation, but rather, that there exist perspectives such that if we presuppose any such perspective, we obtain a particular, definite world as a result. If we combine this with the above insight that there are elements of knowledge about one’s own state that are certain, needing no further justification, then we obtain that these imply similarly certain elements of knowledge about the world as seen through one’s own perspective.

To make this abstract idea more tangible, another favorite analogy of mine is the following. Take a blank piece of paper. It has a very simple description—very little information is needed to fully describe it. Now tear it in two: the edges of the tear will be something very complicated and hard to describe, in general. Describing any of the two pieces in isolation will need a large amount of information—you have, it seems, created information out of nothing. But that is only true if you forget about the other piece! Combining both again yields the original piece of paper and its simple description. One might say that relative to the one piece, the other has a high amount of information; but in combination, both have a very low—indeed, zero in the limit—complexity: their union vanishes into nothingness.

Moreover, the jagged edges of one piece determine that of the other. So, knowing the outline of one, you also know the outline of the other. Now suppose that one of the two pieces represents your subjective experience. If you have access to the properties of that subjective experience, you also have access to the complementary properties in the world. Thus, facts of the world are available to you as facts of your own experience, by virtue of their relational nature: relative to the facts of your experience being a particular way, the facts of the world are, likewise. But to the extent that your own subjective experience is safe from the Münchhausen-trilemma, so is your knowledge of the world.

The empty sheet of paper is like the total, entangled state: its parts have no definite properties. But relative to one particular way of tearing it apart, each side assumes a definite character. If we know take one side as fixed—as analogy to the way our subjective experience is accessible to us by its nature—we obtain the definiteness of the other.

Relative to your experience of chairs, tables, coffee mugs, and trees out there in the world, there actually are chairs, tables, coffee mugs and trees out there in the world. (Modulo the usual meddling scientists keeping your brain in a vat, Cartesian trickster demons, and so on. I’m not claiming that our beliefs about the world are necessarily true; merely that there are grounds for such beliefs at all.) This does not make these entities mind-dependent, and thus, does neither collapse to some form of idealism, nor, sadly, grant you power over them by virtue of your will—that the facts about the world correspond to relations between mind and world does not make them any less factual. That I am only a husband because of my wife, and she is a wife because of (her marriage to) me, does not make us any less husband and wife.

(There is a certain kinship between these ideas and the Buddhist notions of emptiness (śūnyatā) and dependent origination (pratītyasamutpāda). I have remarked on this elsewhere.)