by Jochen Szangolies

Who Are You?

I want you to take a moment to reflect on the answer that first came to mind upon reading this question. Was it something related to your job? Are you a baker, a writer, a physicist, a construction worker? Or did you start thinking about your passions—the things you love, the things that drive and inspire you? Perhaps you define yourself by your values: you are who you are, because of what you hold right and good.

Identity has become a central, and somewhat fraught, topic in contemporary discourse. I believe that, in itself, is a sign of progress: in earlier times, identity was not something that was up for discussion; by and large, what made you you was decided by circumstances of your birth. You were born either noble, or a commoner; male or female; free or in bondage—and whichever of those buckets happenstance chose to place you in, would be the central driving force of your fortune. That today, we can worry about, struggle with, and redefine our identities is a sign of increasing self-determination—who we are is no longer just who we were born to be, but a matter of discovery and deliberation.

This development is clearly far from complete. But to further it—as I believe we must, if we are to hope to ever create a truly just society—we need to understand how identity construction works, and what differences of identity mean for a pluralistic society. Freedom of choice entails a struggle of choosing well: most of us have experienced the strange anxiety of selecting from one of the multitude of options within the modern streaming landscape, versus the ease of plopping down in front of the TV, consuming whatever’s on offer with nothing more than a perfunctory complaint that there’s never anything good on these days. This is what psychologist Barry Schwartz calls the ‘Paradox of Choice’: confrontation with an ever-increasing array of options can induce stress, anxiety, even paralysis—as we try to select the best among the options, we worry that whatever we select will prove sub-par, leading to the oft-invoked ‘Fear of Missing Out’ (FOMO) on the truly superior option. And once we have made our choice, we may become locked in, invested in the idea that this choice is the one, true, right one—superior to those of others. Apple products, we may convince ourselves, really are that much better than their Android counterparts, such that anybody who chose differently made, in some objective sense, a mistake.

Such reasoning may have dangerous consequences, if translated into the realm of identity construction. If choosing Android is wrong, but defining of your identity, then that means you, as a person, are wrong. In the bad old days, identity was, more or less, a given, not to be struggled with, a done deal. This invites a certain kind of moral essentialism—a belief that the identity you were born into decides, or perhaps demonstrates, your moral standing. This, of course, is an abhorrent notion, at the heart of most, if not all, of humanity’s greatest atrocities, and something that we may hope to overcome with the separation of identity from one’s circumstances of birth. This is, I think, the great promise of our age: that we are beginning to realize that the identity of a person, and everything connected to that, is not simply baked into them at birth, but the result of an ongoing, active process carried on throughout each individual’s life.

I should be clear here that I am not suggesting that identity is solely a matter of choice, like what flavor of cornflakes one would like for breakfast. It is as much, if not more, a matter of discovery. Also, by ‘choice’, I do not necessarily mean conscious deliberation, but rather, a freedom from being assigned an identity based on readily discernible external characteristics that are themselves just congealed historical accidents. In an ideal world, this means we are free to be who we are, rather than who others would have us be. We cannot choose our history, ethnicity, or sexual preferences, but, in that ideal world, they no longer determine our value. Choice, then, means autonomy over heteronomy.

Other aspects are more obviously a matter of deliberate choice. What congregation we belong to, or which political party we support: these are at least partially consequences of our own self-determination. And with every choice thus made comes the danger of considering those who choose differently to have made a mistake, and with that, the same looming threat of moral essentialism: only those people are right and good who made the same choices I did. Moreover, these mistaken choices are now not due to mere accidents of birth, but rather, due to active deliberation—and thus, the sole responsibility of those making these choices.

Now, I’m not advocating a relativist picture here. Some choices are better than others. Karl Popper formulated the ‘Paradox of Tolerance‘: a tolerant society cannot tolerate intolerance, or else, will itself collapse into intolerance. But it is important, here, to take care in adjudicating what to tolerate, and what to oppose. As Popper writes:

I do not imply, for instance, that we should always suppress the utterance of intolerant philosophies; as long as we can counter them by rational argument and keep them in check by public opinion, suppression would certainly be most unwise. But we should claim the right to suppress them if necessary even by force; for it may easily turn out that they are not prepared to meet us on the level of rational argument, but begin by denouncing all argument; they may forbid their followers to listen to rational argument, because it is deceptive, and teach them to answer arguments by the use of their fists or pistols. We should therefore claim, in the name of tolerance, the right not to tolerate the intolerant.

The question, then, becomes one of when to tolerate other’s choices, even if they run against our core values, and when not to. I don’t think there can be any hard-and-fast answers here, for the simple reason that any such answer would lend itself to becoming a dividing line between the good and right, and the base and wrong. But I believe that there are considerations that can help us decide when to be accepting towards dissent, and when to oppose it with any force necessary.

Error, Ignorance, and Evil

Suppose that, perhaps intrigued by the above quote, you go to your local bookseller, and buy a copy of The Open Society and its Enemies, priced at $31.99. You hand over $35, collect your change, and leave.

Only later at home do you notice that you’ve only been given $2.01—missing one dollar. Now, most people won’t get terribly outraged at being shirked out of a buck; but suppose that money, and scrupulousness in financial transactions, featured strongly in your moral values. This might lead you to consider the bookseller crooked, morally deficient—wicked, in this sense: they have acted against your values, and their lack of moral fortitude was to your detriment. You might consider them of lesser moral standing, or worse character, and perhaps no longer patronize their bookshop.

The driving force behind these actions is a belief that those who act immorally are of worse character—a position known as virtue ethics, and generally associated with Aristotle. Strictly speaking, in virtue ethics, morality is connected to the identity of the individual, not to their actions—but actions are where character shows itself. Virtue leads to right moral action; conversely, moral wickedness may be taken to betray a lack of virtue.

In its simplest form, I think, an instinct that wicked is as wicked does pervades much of modern society. Emblematic of this is that the dominant reaction to wicked action is punitive in nature: from the parent scolding the child, to fines and jail time.

However, this instinct sits uneasily with a notion of identity as involving a measure of choice. For then, the wickedness becomes a deliberate one—put starkly, the bookseller chose to wrong you, because they chose that sort of identity. The most evil choice is the choice to be evil. We may excuse those that can’t help themselves, whose evil may be due to pathology or compulsion; but the evil of those capable of deliberating between right and wrong, yet choosing the latter, is inexcusable. Faced with this, an opposition that results in ostracism and perhaps even force, punitive or even preventative, might not seem misguided.

But this instinct is not without alternatives. What’s at issue here is the notion of hamartiology: the question of how sin enters into the world. The Christian answer relates it back to the original sin of disobedience against the will of God: a choice of wrong over right, summarily punished by expulsion from paradise.

But consider, for instance, that the bookseller simply miscounted their coins: they intended to give you the right amount of change, but simply made a mistake. Their wicked act then is not due to malice, but due to simple error—and error need not be punished, but may be corrected.

Or, they might not have known their act was morally wrong—that is, they might’ve been ignorant of either the facts of the case (such as the price of the book), or the moral principles themselves. In this case, education, not punishment, would be the proper reaction.

These are the three ways in which the Islamic philosopher al-Fârâbî, who lived around 900 CE, considered we might fail to pursue ‘ultimate felicity’ (by which, in the time-honored tradition of philosophers, he mostly meant philosophical enlightenment): through wickedness, error, and ignorance. These, al-Fârâbî held, were the main impediments to creating a perfect society, where individual happiness for all could be attained.

Thus, it is my main contention that in present-day society, the imputation of wickedness has come to be the default stance, to the detriment of the project of liberating identity construction: those who we judge wicked are, by and large, those which we, with Popper, feel justified to remove, by force if necessary—to cast out from paradise, so to speak. If wickedness is then attributed too quickly, we run the danger of rebuilding the old barriers between us, who choose the good, because we are good, and them, who choose evil out of their inherent wickedness—a relapse into the same moral essentialism that we strive to overcome.

Stumbling Aztecs and Confused Buddhists

If our society is too preoccupied with wickedness as the sole source of moral failings, perhaps it helps to look to history and other cultures to find alternatives.

Aztec society, in the in this context somewhat mislabeled ‘West’, is not typically associated with great moral insight. If you know one thing about the Aztecs, it is their practice of human sacrifice, rightly abominable to modern sensibilities. But they had a sophisticated notion of what it means to live ‘the good life’: the goal is to achieve neltiliztli, a Nahuatl word roughly meaning ‘rootedness’, which carries a figurative meaning of ‘truthfulness’ or ‘authenticity’. This is not a pursuit of happiness, as such—happiness was more or less an incidental outcome.

The greatest obstacle to achieving neltiliztli is encapsulated in the metaphor of the slippery earth: we are all trying our best to achieve balance, but the earth is tlalticpac, slippery and slick—keeping balance is hard, and even those of morally solid character may stumble and fall. Crucially, this shows an awareness that despite one’s best efforts, living the moral life is a task which we may fail: it’s something that’s just hard to get right. But such failure is simply, then, the consequence of the task’s difficulty, not an imputation against individual character. Good people may do bad things through error, or failure—a circumstance which should invite assistance, rather than punishment.

Aztec moral philosophy then also had a strongly communal element. The philosopher Sebastian Purcell, to illustrate this, tells a story about how he complained to his wife that he was unable to resist satisfying his sweet tooth—who then reacted by giving away the sweets they had stashed, thus removing the temptation to ‘slip up’. Purcell did not overcome his vice, but found resources in the community to reduce the opportunities for moral error. The end result is much the same: the transgression ceases, the guilt is alleviated, and it becomes easier to keep balance (on the scales as much as on the slippery earth, one presumes).

Such notions put the locus of moral action not merely at the level of the individual, but seeks it within the community. Consequently, wicked deeds are not cause to cast out the individual that has revealed themselves to be wicked, but rather, to reach out, to try and assist, to steady others in their walk on the slippery earth—not to recoil in fear of the mud rubbing off on us. (Compare also the likewise communally oriented African ethical concept of Ubuntu.)

But communal notions of morality themselves carry a danger of ‘externalizing’ the reasons for morally aberrant behavior—to ‘blame society’, so to speak, for individual misdeeds. However, even at the level of the individual, we are not limited to attributing bad deeds to essential faults of character. This is al-Fârâbî’s third option: moral failure through ignorance.

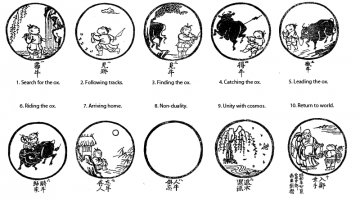

Perhaps the most sophisticated such theory can be found in the Buddhist belief system. In Buddhism, avidya, ignorance, is one of the root causes of dukkha, suffering. In particular, those ignorant of the doctrines of no-self (anatta) and impermanence (anicca) cause suffering by selfish or greedy actions—suffering not just to others, but also their own, as these actions tend to reinforce their misperception of the world, and thus, keep them from breaking free from the cycle of dukkha. The enlightened, by contrast, in a sense can’t help but to act morally; realizing oneself as a ‘selfless person’ makes selfish action nonsensical, an argument also echoed in Derek Parfit’s seminal Reasons and Persons.

The path towards enlightenment, however, is a fraught and difficult one, and may not be for everybody. But we can still take something away for our more mundane daily struggles: if we feel wronged, it may be that those who wronged us did so simply because they didn’t know better. In this case, too, punishment is not the right reaction—education is.

Thus, next time a shopkeeper cheats us out of a buck, we might consider that maybe, they didn’t do it out of wickedness, an inherent flaw in their moral fibre, and that thus, the right response is not one of punishment; we might seek a way of resolving the issue that unifies, rather than divides. That’s not to say that punishment, ostracism, even force are never the right response—with Popper, we should absolutely claim ‘the right not to tolerate the intolerant’. But rather than a default instinct, this should be seen as a last resort.

Moral essentialism—the idea that some people are of intrinsically higher moral standing than others—is at the heart of many of humanity’s worst moments. The unmooring of identity from accidents of birth or heritage, incomplete though it still is, is our best bet for overcoming this notion: none of us are born, or fated, to be less than another. But we must take care: the habitual association of virtue to character threatens to reintroduce moral essentialism through the backdoor, in tying choices made in identity construction to an inherent moral flaw in those making them.

Progress, perhaps, might be made by fostering a notion of mutualism: engaging with one another to discover, and, if possible, eliminate the reason why they did us wrong, rather than dissociating us from them in response to their wrongness. Such mutualism is the antithesis of the mere exposure of social media: it is the framing of a shared world, rather than the bombardment of each other with our manufactured individuality. Finding value in each other’s differences, without judging them inherent flaws of character, rather than trying to convince one another that the way we are, and the way we live, is the best way to be and live—or at least looks best on Instagram—may then also be the means to warm up our ‘chilled’ social climate.