by Derek Neal

In 1965, John McPhee wrote an article for The New Yorker titled “A Sense of Where You Are.” The piece profiles the basketball player Bill Bradley, at the time a member of the Princeton basketball team. The subtitle of the essay is the question: What makes a truly great basketball player? McPhee goes on to answer the question, and in doing so, highlights certain characteristics that could apply to great athletes in other sports. What defines a great basketball player, it turns out, can also define a great soccer player or hockey player. I was struck by this while watching Lionel Messi in the World Cup, noticing the similarities between his game and Bradley’s.

In 1965, John McPhee wrote an article for The New Yorker titled “A Sense of Where You Are.” The piece profiles the basketball player Bill Bradley, at the time a member of the Princeton basketball team. The subtitle of the essay is the question: What makes a truly great basketball player? McPhee goes on to answer the question, and in doing so, highlights certain characteristics that could apply to great athletes in other sports. What defines a great basketball player, it turns out, can also define a great soccer player or hockey player. I was struck by this while watching Lionel Messi in the World Cup, noticing the similarities between his game and Bradley’s.

McPhee notes how Bradley “starts slowly, as a rule. During much of the game, if he has a clear shot, fourteen feet from the basket, say, and he sees a teammate with an equally clear shot ten feet from the basket, he sends the ball to the teammate.” Messi is also a slow starter. In fact, he often stands around for the first few minutes of the game, strolling leisurely and appearing as if he’s just happened to wander onto a soccer pitch. This exasperates some commentators and fans, much in the same way that Bradley’s coaches “clutch their heads in despair” when it doesn’t seem like he’s putting forth maximum effort. They think that the quality of someone’s play can be measured by how much energy they exert, and that the visible signs of exertion, such as sweating and heavy breathing, indicate a positive performance. This is not the case, and in fact proves just the opposite. A player who must run more than the others does so to compensate for a lack of skill and talent. At best, this player succeeds due to hard work and perseverance; at worst, they become what my dad used to say whenever I or one of my siblings would have a poor game: a chicken with its head cut off, or a dog after a bone. Much has been made of Messi’s walking and standing, but the general consensus is that he does this in order to gain an understanding of where the opposition will be positioning themselves, which then allows him to find space and exploit it for the remainder of the game. In other words, Messi is developing a sense of where he is on the pitch.

By seemingly knowing where his teammates and the opposition are without looking, Messi is able to make decisions based on assumptions of where people should be if they are playing correctly. This is something McPhee notes about Bradley as well. He writes that Bradley “[does] what few people ever have done—[play] basketball according to the foundation pattern of the game.” What I take this to mean is that Bradley makes the correct decision—the most efficient, highest percentage play—in every situation. This is an effective strategy, in fact, the best strategy when one is playing with other like-minded, highly skilled teammates, but it can be detrimental to a team’s success if the majority of the players are not at the level of nor complementary to the team’s star player. McPhee provides an example of this with Bradley. He writes how “other Princeton players aren’t always quite expecting Bradley’s passes when they arrive, for Bradley is usually thinking a little bit ahead of everyone else on the floor. When he was a freshman, he was forever hitting his teammates on the mouth, the temple, or the back of the head with passes as accurate as they were surprising.”

This could be a description of Messi for most of his career with Argentina. Up until the past 18 months, when Messi has led Argentina to victories in the Copa América and World Cup, Messi had always had more success with his club team, Barcelona, than with the national team. This was largely due to the players on Barcelona being better than those on Argentina. With Barca, Messi could make the correct play and expect his teammates to do the same. He would give the ball to them, and they would give it back to him. With Argentina, his teammates held on to the ball too long or weren’t ready for his passes. This led to Messi having to try and do too much, which is antithetical to his nature as a player. Messi, like Bradley, is a playmaker as much as a scorer, and he wants to make the right play every time, even if that means giving the ball to a player of lesser talent in a better position.

In 2014, when Argentina lost the World Cup final to Germany in extra time, Messi frequently set his teammates up to score, but they were unable to finish. Perhaps unfairly, their striker Gonzalo Higuain became the scapegoat for the loss due to his missed opportunities. In 2022, the story was different. Messi’s teammates, many of whom had grown up idolizing him, tailored their games to his style of play and were prepared for his seeing eye passes and deceptive maneuvers. The epitome of this came in the quarterfinal against the Netherlands. 35 minutes into the match, Nahuel Molina dropped the ball off to Messi on the right side of the pitch, just inside the Dutch half. Messi begins to cut inside towards the goal, the ball attached to his left foot. This looks like it might be one of Messi’s patented, driving runs where he sets up to curl a shot towards the far post, but he’s surrounded by seven Dutch players and even for him, this seems like an unlikely proposition. Meanwhile, Molina has sprinted towards the Dutch back line from behind Messi, unseen by the defenders who are, to use my dad’s parlance, focused on Messi like a dog after a bone. Messi stops cutting and starts drifting laterally. The danger seems to be over, and the Dutch defender closest to Messi decides to pounce to dispossess him of the ball. The other defenders relax. But Messi has simply lulled them to sleep and waited for this moment, the moment when Molina is in line with the last Dutch defender, to pass the ball against the grain, in the opposite direction that everyone is moving, and set his teammate up for a goal. Molina takes a touch and puts it in the corner. 1-0 Argentina. Messi never looked at Molina.

This pass was described in The Guardian’s match report as a “glorious eye-of-the-needle pass,” and its genius can be seen in the reaction of Molina, who points and sprints to Messi. In soccer, the team usually runs to surround the goal scorer, but in this case, they surrounded Messi, recognizing that he was responsible for the creation of the goal. Messi’s teammates in 2022 are a bit like Bradley’s teammates in his senior year. McPhee writes: “His teammates have since sharpened their own faculties, and these accidents [being hit by a pass] seldom happen now. ‘It’s rewarding to play with him,’ one of them says. ‘If you get open, you’ll get the ball.’ And, with all the defenders in between, it sometimes seems as if the ball has passed like a ray through several walls.” Or through the eye of a needle, one might say.

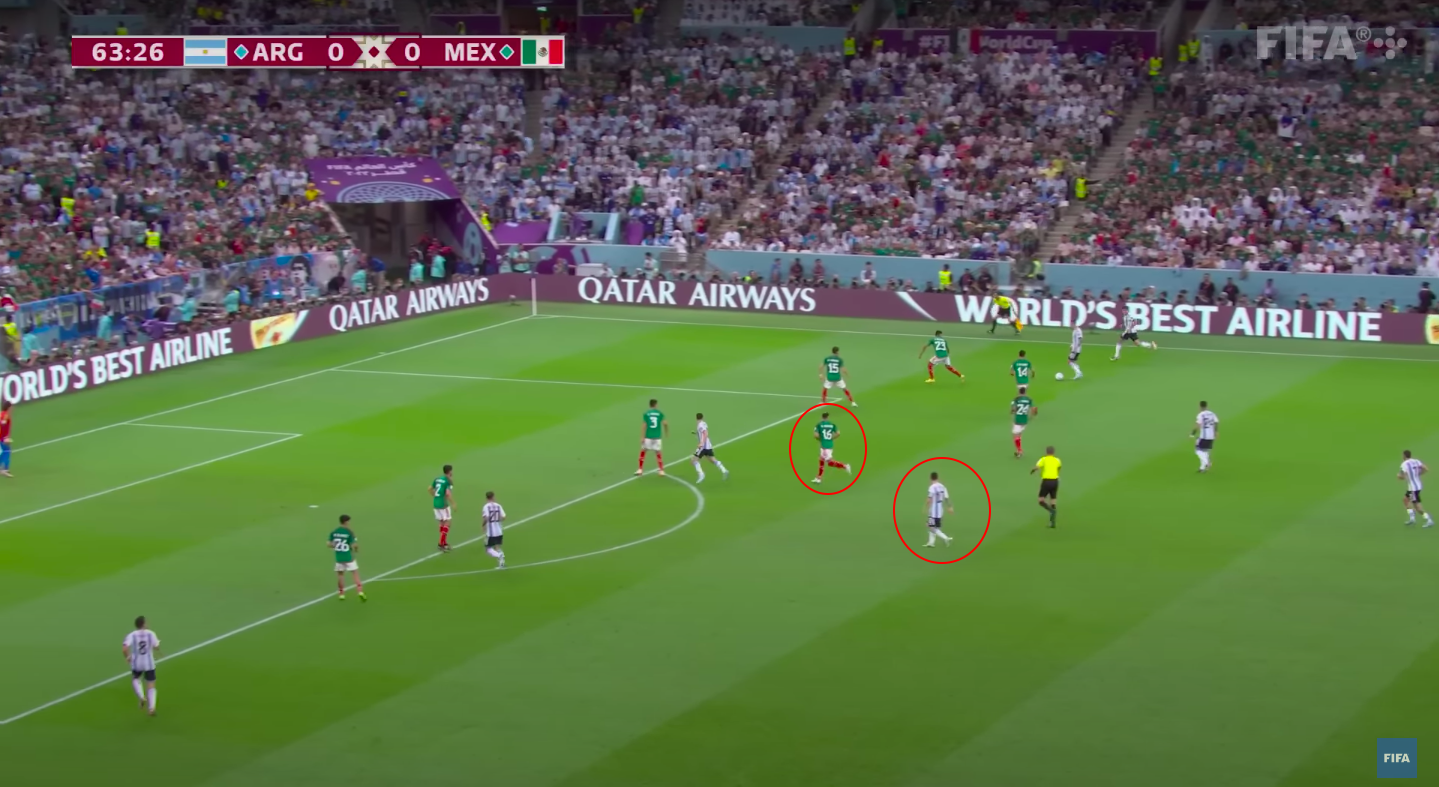

The title of McPhee’s essay comes from a quote by Bradley when he’s describing a reverse layup that he’s perfected: “he [Bradley] tossed a ball over his shoulder and into the basket while he was talking and looking me in the eye. I retrieved the ball and handed it back to him. ‘When you have played basketball for a while, you don’t need to look at the basket when you are in close like this,’ he said, throwing it over his shoulder again and right through the hoop. ‘You develop a sense of where you are.’” A similar moment was Messi’s goal in the group stage against Mexico. Argentina is attacking, moving towards goal, as Mexico is retreating, positioning themselves between the attackers and the net. Enzo Fernandez, an Argentinian midfielder, plays the ball out wide right to Angel Di Maria, an Argentinian forward. Messi is in the middle of the pitch, being tracked by a Mexican defender, but when this pass is made, he slows down and starts walking as everyone else, the defender included, continues to jog. Eventually Messi stops, and it’s as if he’s a grain of sand that’s been left behind as the tide goes back out to sea. Suddenly, by virtue of doing nothing, Messi is wide open at the top of the box, in prime goal scoring position. He knows where everyone else on the pitch will move to, he knows where the goal is, and he knows where he is in relation to them. All that’s left is for his teammate to comply and give him the ball, which Di Maria does. Messi takes one touch and fires the ball into the corner, too quickly for anyone to stop him. What’s striking about both plays, Messi’s pass against the Netherlands and his goal against Mexico, is that in both cases nothing much seems to be happening in the game, until suddenly there’s a goal.

(Image 1) Messi runs towards goal and is followed by a defender as the ball is played wide right.

(Image 1) Messi runs towards goal and is followed by a defender as the ball is played wide right.

(Image 2) Messi stands still as others keep moving toward goal, creating space to receive the ball and shoot

(Image 2) Messi stands still as others keep moving toward goal, creating space to receive the ball and shoot

Why did John McPhee feel compelled to write a profile of a collegiate basketball player in 1965? Why must I write this essay in 2023 about a soccer player? It’s difficult to put into words, but it is clear that Bradley and Messi both invoke feelings of awe and wonder in spectators who then feel the need to relay their experience to others. When Messi set up Julian Alvarez’s goal in the semifinals against Croatia, twisting and turning to lose his defender, I texted my dad and brother: are you witnessing this!? I chose these words deliberately because what we were watching seemed to be beyond what the physical world allows—a miracle. McPhee describes three such moments in the career of Bradley, once when he performed such an impressive array of shots in his warm-up that the crowd started “applauding like an audience at an opera” and twice when Bradley received a standing ovation from opposing crowds upon exiting the floor before the game was over (an extremely rare occurrence). In these cases, there is simply the need to bear witness.