by Michael Liss

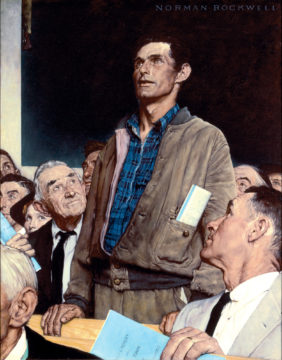

I’ve always liked this image. It’s quiet, it sneaks up on you, brings back old memories of pizza parlors, barbershop walls and drug-store soda fountains.

Norman Rockwell’s “Four Freedoms” had been inspired by FDR’s 1941 Annual Message, given at a time when Germany had swept through much of Europe, and democracy was in great peril. While the United States was not then yet at war, and isolationism was still strong, a growing number of Americans could see that our involvement might be inevitable. Roosevelt wanted to define the values that a post-war world would embrace. Drawing from the Constitution as well as from the lived experience of the Depression, FDR called for Freedom from Want, Freedom from Fear, Freedom of Worship and Freedom of Speech.

This one is Rockwell’s masterpiece. The composition was, according to him, inspired by a town meeting he had attended, where a young man took an unpopular position. Rockwell portrays him with shoulders thrown back a bit as he speaks, as if to project his unamplified voice through the hall. His hard, weathered hands hold the chair in front of him, a copy of a Town Report folded in his pocket. His face is roughened by the sun and wind, he’s flanked by two older men in white shirts and ties, and, on the face of one, there’s a small smile. No screaming, no doxing, and certainly no video captured on someone’s phone, uploaded, and seen by hundreds of thousands of partisans.

Rockwell’s painting gets to the essence of “Constitutional” free speech. However contrary this speaker’s opinion is, it is his right to voice it at a public hearing without fear of punishment. The First Amendment has very few content-based exceptions—the government can intervene only where obscenity, defamation, fraud, incitement, and speech integral to criminal conduct is involved.

Still, there’s so much ugliness out there, divisive and insulting words, bizarre theories, outlandish political memes, accusations that are just disgusting. The idea that “there ought to be a law” enjoys a considerable amount of public support. Even the Framers found the application of Free Speech less enjoyable than the theory. Talking smack about one’s political opponents is as old as the Republic. So is trying to find creative ways to keep them from talking smack about you.

Efforts to enact broad-based legal restrictions on speech have never worked—the examples of it, like the Alien and Sedition Acts, are despised. Perhaps that’s a function of the fact that, in nearly 250 years, we’ve never been able to develop a sustained consensus as to our political vocabulary. Free speech works because we don’t trust others to define that vocabulary for us.

Enter Elon Musk, self-defined Free Speech Absolutist, and new owner of one of the world’s most influential social media sites. Can Musk open the Pandora’s Box that is a largely unmoderated Twitter?

Before we get there, let’s define some terms. Musk is a person, not the government. He, Musk as Musk, has the same rights every other American has, and more specifically, the same rights as that young man in Rockwell’s painting. That his megaphone is exponentially bigger increases his reach, but does not diminish his rights. And just as he can say what he wants, subject to those very limited exceptions, so, too, can he close his ears to anyone he wants. Musk as Musk can block people to his heart’s content. He need not publicize or apply a consistent standard.

Twitter itself is also not the government, so it does not have the same Constitutional limitations as the government does. Twitter doesn’t have Musk’s “person” superpower, but it does have a superpower of its own, Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act of 1996. More on this is a bit.

Let’s talk Adam Smith for a moment, especially because we might like to see both Musk and Twitter use their superpowers “for good.” The fact is that just because Musk or Twitter can do something doesn’t completely insulate them from the judgment of the marketplace if they do it. Musk’s ownership of Twitter is somewhat analogous to his owning “Elon’s Bar and Grill.” It’s his toy, and, so long as no laws are broken, he can do what he wants with it. If Elon’s Bar and Grill wants to host supremacist outlaw biker groups three weekdays and a fight club on Sunday, it’s still Elon’s choice.

Of course, there’s a potential price, something I’ll call “Dalton’s Law” after Patrick Swayze’s bouncer character’s line in the B-movie Roadhouse: “People who really want to have a good time won’t come to a slaughterhouse.”

Dalton’s Law tells us that the more of a mess Musk makes of Twitter, the more likely it is that some—some—folks will choose not to come to his abattoir. I use Twitter. I liked it. Its interface is easier and more intuitive than others—at least for now—but it’s demonstrably worse than it was a few months ago. Many of the folks I know (or follow) have started migrating to Mastodon, and some have left the Twitter platform entirely. Is that important? Not nearly as much as we might think. An email I got from an academic friend who left some time back is what I’d call the “harsh but fair” type: “When I first got off Twitter, I had to keep reminding myself, ‘No one really cares what you think.’ There’s a certain hubris about it that makes you think that you aren’t doing it for yourself, you’re doing it for other people.”

My friend is right. While I’m sure every one of my modest cadre of followers open their Twitter app with an unquenchable thirst to see my incandescent brilliance, the loss of me, or one million like me, wouldn’t put a dent in a platform that has an estimated 450 million monthly users.

The people Musk should care about, the ones who give teeth to Dalton’s Law are (a) the news organizations, journalists, and celebrities that use Twitter to raise their profiles, market their brands, and gain eyeballs for their products, and (b) the advertisers, who pay real money for a presence and for whatever spots in Twitter’s algorithm drive customers to their sites.

Right now, there remains a symbiotic relationship—the groups’ need each other more than the current roughness pushes them away. The Twitter platform remains just too big, so the Invisible Hand of competition hasn’t (yet) passed judgment.

I expect it to stay that way. Whatever flaws Musk has, he’s not an idiot. He may push boundaries, I may not like the look and feel of the site, but I think he will largely keep his promise to advertisers that Twitter won’t become a “hellscape.” Those advertisers are cold-blooded themselves—remember this is a group that initially withdrew campaign contributions to election deniers after the January 6th riot, and then found it in their hearts to forgive and forget when the legislative process resumed and there were politicians to purchase. They also know that Musk has an ace up his sleeve: Some Republicans have promised investigations of advertisers who leave Twitter, and there’s little a CEO likes less than answering hostile questions posed by ill-informed Congressmen looking for a microphone.

I think Musk is a very smart, extraordinarily wealthy man having a very good time. If he can solve his secular problem of a shrinking of the core of technical expertise to keep the site running, then he’s bought a platform that has an extremely strong market position. A few defections will not materially dent it. In short, I’m not nearly as convinced as others are that the entire house of cards is quite ready to collapse simply because Musk as Musk can be a troll and Twitter as Twitter opens the floodgates to The Dark Side.

That comes with a gigantic qualifier, a qualifier that applies to the rest of the social media giants as well. Musk (and they) desperately need Section 230 to stay pretty much as it is. Section 230(c)(1) is the moat that cordons off Twitter from liability from the content that others create, no matter how randy. Equally important, Section 230(c)(2) empowers those social media platforms to moderate content “that the provider or user considers to be obscene, lewd, lascivious, filthy, excessively violent, harassing, or otherwise objectionable, whether or not such material is constitutionally protected…” (emphasis added).

As a sidenote, it’s fascinating that Musk has hired veteran muckrakers like Matt Taibbi and Bari Weiss to investigate whether the previous management of Twitter was engaged in excessive moderation of conservatives. It’s exactly that type of protected “editorial” judgment that helps keep companies like Twitter out of trouble, and that Twitter would likely want to rely on if it took steps against critics of the company.

Section 230 does seem like a very big gift to the social media companies, and politicians of both parties (including both President Biden and former President Trump) have criticized it. Some of this comes from responsible political leadership: a growing realization that social media draws away attention from healthier pursuits; it groups people in a manner that amplifies radical behavior; it enables nastiness not just in the political arena, but also in the personal one; and it accelerates certain pathologies. These are legitimate problems that need attention, and credit is due to any leaders who make that their focus. Of course, that’s not the reason why many politicians have targeted Section 230. It’s politics that makes the difference.

As we all know, where there’s politics, there is also the courts, and this term, the Supreme Court, at the apparent urging of Justice Thomas, is going to take a hard look at Section 230. There are two cases to be argued before SCOTUS: Gonzales v. Google and Twitter v Taamneh, and both use novel approaches to leap the moat afforded by Section 230.

Gonzales is a case brought by the family of a victim in a 2015 ISIS attack in a Paris bistro. The claim is that Google, through its subsidiary YouTube’s recommendation algorithm, led the assailants to ISIS recruiting videos. Taamneh (brought by another family that lost someone to a terrorist attack) goes even further, asking SCOTUS to rule that a company can be held liable if any pro-terrorism content appears on its website, regardless of the degree and efficacy of any moderation policies it might have in place.

The disposition of these two are worth watching for several reasons. First, if SCOTUS were to permit a litigant like Gonzalez to go after the recommendation algorithms, it would be driving a stake in the heart of profitability. Advertisers want and pay for the boosting and placement those algorithms provide. It’s also what many users want—to be led to sites with additional information/products in which they have an interest. Second, with respect to cases like Taamneh, mandating extensive moderation through essentially unlimited liability would be incredibly costly, and without any guarantee of success. Posters of to-be-banned material are likely to be more sophisticated than the moderators who try to keep them out. Third, since SCOTUS cannot, on its own, rewrite the law, responsibility would pass back to Congress and the President, who are likely to be irretrievably deadlocked.

Taamneh and Gonzales may be just part of the battle. There are two cases waiting in the wings, at the lower court level, that are potentially just as impactful. NetChoice v. Paxton (from the Fifth Circuit) and Moody v. NetChoice (from the 11th) threaten to take the discussion to an area where there may be no good answers. Both involve recently enacted laws in Texas (Paxton) and Florida (Moody) that restrict platforms from removing user-generated content, a direct shot at Section 230(c)(2). Texas and Florida both claim conservatives are being discriminated against, and their laws are intended to make the playing field fairer.

Where does this all go? I can’t make a good prediction. How does one reconcile a potential mandate for moderation that could come out of Taamneh and Gonzales with Governor’s Paxton and DeSantis demanding no moderation? Do conservatives in Texas and Florida upload with some sort of “Get Out of Moderation” NFT attached to the file? Who gives them that Good Housekeeping Seal? What happens if Blue State Governors push for their own criteria?

There are some ways out of this box, if Congress weren’t so completely polarized. It could come to a rational compromise on the extent of a revised Section 230 and then apply the Supremacy Clause, to preempt, say, Texas and California from home-cooking. Social Media companies might even welcome uniform rules with defined safe harbors, even if those cost some (some) money. Remaking the regulatory landscape without threatening the economic viability of the industry ought to have appeal.

Why should we care? Let’s face it, we use social media. If we aren’t on Twitter, maybe we are on Facebook, or Mastodon, or use Google or Bing or Go Daddy to search. We want them to cater to us, but we also want them to survive. We ought to be grownups enough to filter out the material with which we don’t agree without the big hand of the government. Social media, in turn, ought to be smart enough not to violate Dalton’s Law.

In the “good old days” when people wanted to voice their opinions, they went to a town meeting, or wrote a letter to the Editor. If they were persuasive enough, they not only got a hearing but perhaps changed minds. It’s what Freedom of Speech meant to many.

In 1943, Rockwell’s publisher, The Saturday Evening Post, joined with the Treasury to send his “Four Freedoms” (along with works of other illustrators) on a 16-city tour to sell war bonds and stamps. Over one million people saw the exhibit, and they bought $133 million (over $2.2 Billion in today’s dollars) worth of bonds and stamps. Those who purchased were given a set of prints of each of Rockwell’s “Four Freedoms” paintings.

Some of those likely ended up in pizza parlors, on barbershop walls and at drug-store soda fountains. If you happen to spot “Freedom of Speech,” take a close look and you will notice that, of all the people in the picture, the speaker is the only one whose clothes still wouldn’t be out of style.

Happy New Year