by Daniel Shotkin

As a senior in high school, I’ve spent four consecutive years in English classes, during which my teachers have hammered home the idea that fiction follows a set progression—Chaucer, Shakespeare, the Enlightenment, Romantics, Transcendentalism, Victorian literature, realism, existentialism, modernism, and, today, postmodernism. If each past period has been clearly defined—Romantics love the sublime, Modernists reject tradition—then the period we’re in now feels a lot less certain. Today’s stories are diverse, both in genre and style. Still, there’s one trend in modern fiction that has caught my untrained eye: a lack of creativity.

Take a look at the Oscar nominees for Best Film of 2025, and you’ll find a wide variety of stories: a black comedy about a New York stripper marrying a Russian mafia heir, a drama about a Hungarian architect emigrating to the United States, and a Bob Dylan biopic. Despite the diversity in characters, settings, stories, and genres, there’s still one aspect the Academy has failed to account for—fiction.

Of the ten nominees, only three are original works. A Complete Unknown, The Brutalist, I’m Still Here, and Nickel Boys are, for all intents and purposes, biopics. Conclave, Dune: Part Two, and Wicked are adaptations of existing works. The only fully original films recognized by the Academy are Anora, Emilia Pérez, and The Substance. While it’s not my place to dictate what happens behind the scenes of film nominations, this disregard for imaginative fiction isn’t unique to filmmaking.

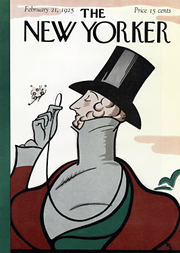

Flip through an issue of The New Yorker from the past five years, and you’ll find op-eds, long-reads about niche subjects, and, almost always, a short story. Fiction has been central to The New Yorker since its inception, yet, for a magazine with such literary weight, too much of the fiction featured is, to put it mildly, dull.

Though I can’t claim to have read every New Yorker short story, most of the ones I’ve encountered struck me as long, meandering reads that painstakingly describe the lives of mundane characters. The protagonists tend to be academics, office workers, baristas, writers, mothers, fathers, and, not surprisingly, New Yorkers. These characters’ struggles—relationships, deaths, mortgages, race, cultural differences—are usually relatable. To be clear, I have no issue with the representation of these characters or struggles, and I certainly don’t think these works are unworthy of attention. It just seems to me that we aren’t tapping into the full potential of fiction.

Though I can’t claim to have read every New Yorker short story, most of the ones I’ve encountered struck me as long, meandering reads that painstakingly describe the lives of mundane characters. The protagonists tend to be academics, office workers, baristas, writers, mothers, fathers, and, not surprisingly, New Yorkers. These characters’ struggles—relationships, deaths, mortgages, race, cultural differences—are usually relatable. To be clear, I have no issue with the representation of these characters or struggles, and I certainly don’t think these works are unworthy of attention. It just seems to me that we aren’t tapping into the full potential of fiction.

Producers have million-dollar budgets at their command but choose to show stories we’re already familiar with. Writers can put anything their mind imagines to paper, yet many choose to depict experiences we already live. So what’s the alternative? First, it might be more helpful to define what’s missing.

One element that’s largely absent is magic. Most “serious” modern works of fiction—the kind nominated for awards—rarely feature supernatural or surreal elements. Of the last five Nobel Prize winners in Literature, only the most recent, Han Kang, incorporates any kind of magical elements in her work. It’s clear that most critically lauded works focus strictly on the real world.

Why is magic important? For one, it elevates a story. To me, works that ground themselves too heavily in the real world inevitably succumb to the same dullness of the world they inhabit. Magic—whether in the form of superpowers, ghosts, or surrealism—allows a story to break free from the constraints of reality, expanding its scope.

As kids, most of us were constantly exposed to magic as a plot device. Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, Harry Potter, Alice in Wonderland, The Wizard of Oz—most of the fiction kids are most attracted to feature some form of otherworldly elements, whether that be Oompa-Loompas or magic wands. So, in many ways, children’s fiction, with its embrace of magic, is far more inventive and vibrant than what most adults are ever exposed to. But that doesn’t mean adult fiction can’t be imaginative, too.

In my opinion, some of the most creative fiction of the past fifty years has come from Latin America, where magical and serious fiction were never divided into distinct spheres. A prime example is Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude, a multi-generational family saga set in the mythical town of Macondo, filled with curses, prophecies, and other supernatural events. Another example is Jorge Luis Borges, whose short stories explore infinite libraries, parallel dimensions, and mythical creatures. This literary tradition persists today, as seen in novels like Álvaro Enrigue’s You Dream of Empires—a hallucinatory retelling of the historic encounter between Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés and Aztec emperor Moctezuma in 1519.

Another device that deserves more attention is metafiction. Turn to Act 3, Scene 2 of Hamlet, and you’ll see exactly why metafiction can be so rewarding. Hamlet, suspecting that his uncle-turned-stepfather Claudius murdered his father, stages a play that mirrors the crime. He calls the play The Murder of Gonzago and carefully observes Claudius’s reaction, hoping to catch a guilty conscience. As the performance unfolds, Claudius grows increasingly agitated, eventually storming out—confirming Hamlet’s suspicions. While this plot device sounds run-of-the-mill to our twenty-first-century ears, I find it incredibly satisfying.

Consider how Shakespeare could have confirmed Claudius’s guilt: a well-placed spy or a dramatic confrontation. But instead, Shakespeare relies on a play within a play. Not only does this heighten the sense of drama in this scene, but it also serves another important purpose—entertainment. A play within a play is inherently captivating—actors are shrouded in another layer of character, the action becomes veiled in irony, and Shakespeare gets to drop Easter eggs for those with a sharp literary ear (he even references his own Julius Caesar at the beginning of the scene).

Metatextuality also isn’t unique to Shakespeare. The Canterbury Tales, Don Quixote, Slaughterhouse-Five, Pale Fire—the list of metatextual works goes on and on. The Canterbury Tales, Don Quixote, Slaughterhouse-Five, Pale Fire—the list of metatextual works is long. Stories that examine fiction itself have been around as long as fiction itself. They allow authors to explore abstract ideas—concepts we can’t experience in everyday life but that are accessible only through fiction.

In the end, it’s hard to assign a specific issue to modern fiction as a whole. There are many exceptions to my argument—horror movies continue to churn out supernatural plots, and some great metafiction has been published in recent years, like Mark Danielewski’s House of Leaves. But, then again, the cultural institutions that shape what high schoolers like me will be reading forty years from now also seem to undervalue the power of imaginative writing. If we dismiss magic, surrealism, and metatextuality as elements of serious fiction, we also ignore a rich tradition of stories that have relied on exactly those devices. So, next time you read another boring piece of fiction, know that an alternative is possible—it just requires a bit more creativity.

***

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.