by Leanne Ogasawara

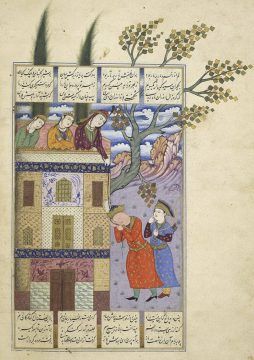

One God, One Farinelli…

Stepping onto the stage, the singer draws in a long breath as he gazes out across the audience. For a moment, he is blinded by the light of innumerable candles. So lavishly lit, it is a miracle that the theater didn’t burn down more than it did over the years. Over a hundred boxes rise up in six tiers in front of him; each box with a mirror affixed on the front reflecting the twinkling light of the two candles placed on either side. The singer can just make out the bejeweled king and queen sitting in their royal box with its gigantic gold crown hovering above. This was the Teatro di San Carlo in the Kingdom of Naples, considered during the 18th century to be the greatest opera house in the world. And on this night, people had come from far and wide to hear Farinelli sing— Farinelli, the famed castrati singer, who drew great crowds and commanded princely sums wherever he performed.

But what a price he had paid to stand on this stage.

The deplorable practice of mutilating young boys to preserve their adolescent voices began in Italy as early as the 12th century. But castrati voices are something we associate most closely with 17th-18th century Baroque music. At that time, women were not allowed to sing in church or on stage in the Papal States, and so the practice began of seeing men singing the roles of women. But this was not like in Japan in Kabuki theater, where you still see men exclusively performing the roles of women; for in Italy these were not men dressed up as women –but rather were those who had undergone castration as children. The church alone cannot explain the huge popularity of their voices throughout Europe. In Naples or London, for example, women had never been banned from appearing on stage, and yet castrati regularly appeared alongside female sopranos.And they were wildly popular. Rock stars, is how we would describe them today. Read more »

Johnny spoke softly in a voice just past the threshold of manhood. His smile, mistaken for charm, was longing. I could see the pentimento of the child still in him.

Johnny spoke softly in a voice just past the threshold of manhood. His smile, mistaken for charm, was longing. I could see the pentimento of the child still in him.

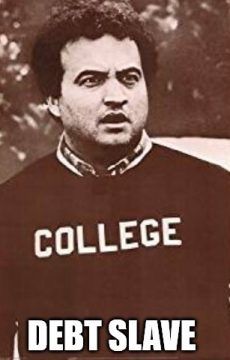

It does not take long for history to repeat itself. It was only a little over a decade ago that overzealous lending, lax underwriting standards, unrealistic collateral valuations, borrowers not understanding loan terms, an exploding derivative securities market–and a dozen or so other factors–led to a massive crash in the housing market. Today in the United States we have outstanding student loan debt of $1.5

It does not take long for history to repeat itself. It was only a little over a decade ago that overzealous lending, lax underwriting standards, unrealistic collateral valuations, borrowers not understanding loan terms, an exploding derivative securities market–and a dozen or so other factors–led to a massive crash in the housing market. Today in the United States we have outstanding student loan debt of $1.5

While Trump’s immigration politics makes international headlines almost every day, the disaster of the European immigration policies rarely becomes international news. A recent exception is the case of Captain Carola Rackete, and it is a telling one. With all the potential for a good story, Rackete’s journey is both standing for and at the same time distracting from the actual complex mess of European immigration politics.

While Trump’s immigration politics makes international headlines almost every day, the disaster of the European immigration policies rarely becomes international news. A recent exception is the case of Captain Carola Rackete, and it is a telling one. With all the potential for a good story, Rackete’s journey is both standing for and at the same time distracting from the actual complex mess of European immigration politics. When the flight delay is announced, we ask what it is we have done wrong. From airlines and the world at large, the answer is rarely forthcoming, so we must look inward instead.

When the flight delay is announced, we ask what it is we have done wrong. From airlines and the world at large, the answer is rarely forthcoming, so we must look inward instead.

There is a great deal of literature available on the experiences of the horrors, suffering and the injustice that the Jewish people experienced during World War II. Bart Van Es’s The Cut Out Girl adds to that literature.

There is a great deal of literature available on the experiences of the horrors, suffering and the injustice that the Jewish people experienced during World War II. Bart Van Es’s The Cut Out Girl adds to that literature.

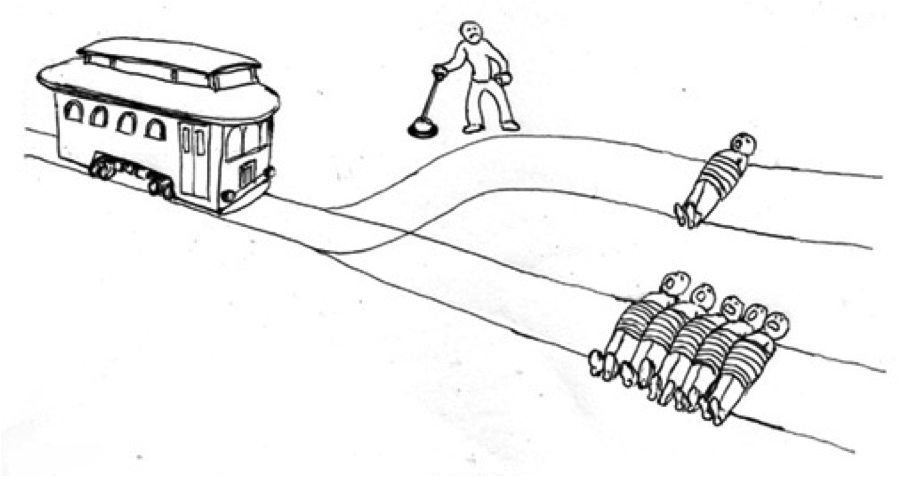

In “The Moral Landscape: How Science Can Determine Human Values” Sam Harris argues that the morally right thing to do is whatever maximizes the welfare or flourishing of human beings. Science “determines human values”, he says, by clarifying what that welfare or flourishing consists of exactly. In an early footnote he complains that “Many of my critics fault me for not engaging more directly with the academic literature on moral philosophy.” But he did not do so, he explains, for two reasons. One is that he did not arrive at his position by reading philosophy, he just came up with it, all on his own, from scratch. The second is because he “is convinced that every appearance of terms like…’deontology’”, etc. “increases the amount of boredom in the universe.”

In “The Moral Landscape: How Science Can Determine Human Values” Sam Harris argues that the morally right thing to do is whatever maximizes the welfare or flourishing of human beings. Science “determines human values”, he says, by clarifying what that welfare or flourishing consists of exactly. In an early footnote he complains that “Many of my critics fault me for not engaging more directly with the academic literature on moral philosophy.” But he did not do so, he explains, for two reasons. One is that he did not arrive at his position by reading philosophy, he just came up with it, all on his own, from scratch. The second is because he “is convinced that every appearance of terms like…’deontology’”, etc. “increases the amount of boredom in the universe.”